ADHD is the New Normal (Op-Ed)

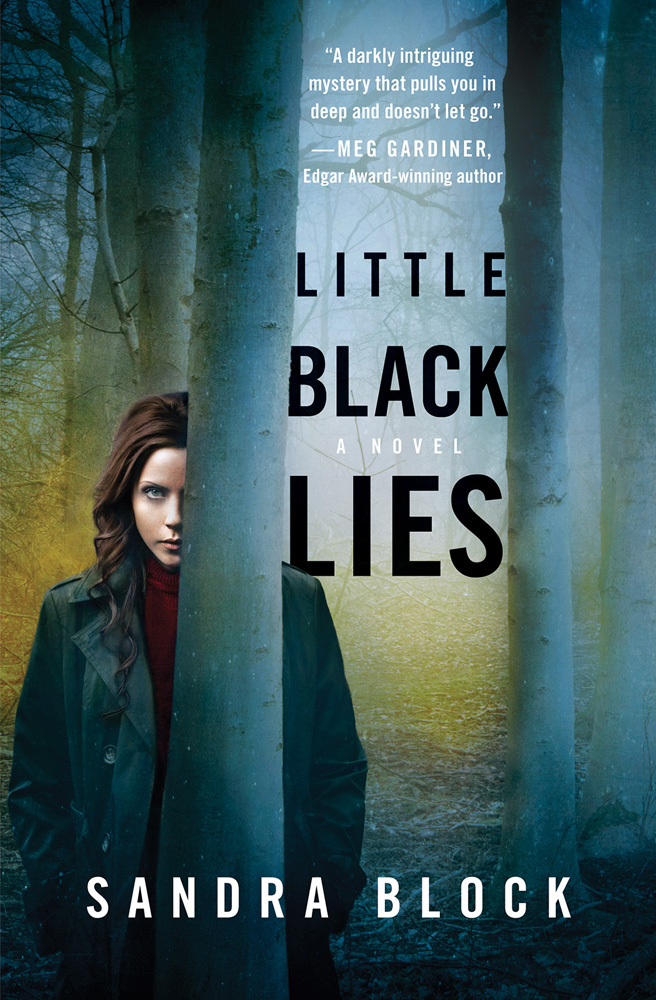

Sandra Block is a writer and practicing neurologist. She graduated from college at Harvard, then returned to her native land of Buffalo, New York, for medical training and never left. She has been published in both medical and poetry journals. "Little Black Lies" is her first novel. She contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

I knew the tide was turning at my daughter's fifth-grade poster presentation. Each student chose a "cause" to present, the definition of "cause" left purposefully vague. Posters of all sizes and shades filled the room, with topics running the gamut from racism to obesity to pet abuse. (I don't remember which cause my daughter picked, but I do remember learning about it the night before, prompting a trip to Walgreen's, some bleary-eyed gluing and a lecture on procrastination.) The children stayed near their posters, so parents could wander around and ask questions, like a soft introduction to abstract-viewing at a research conference.

Perusing the room, I came upon a pink poster with glitter aplenty, boa feathers, and pictures of kids and pill bottles. In sparkly letters, the title read, "ADHD." The child by the poster, a cute, freckled redhead, was telling anyone and everyone about her ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder). She spoke of the challenges this presented and some of the medications she had tried. The message was loud and clear, and to be honest, downright awe inspiring:

"I have ADHD — and I am not ashamed."

As a neurologist, I see my share of ADHD, as well as the purely attentional version, ADD (attention deficit disorder). The disorder is thought to be a heritable condition — though without one particular responsible gene — associated with neurotransmitter or brain chemical dysfunction. Most people have seen these children, perhaps even raised these children. The boy yelling, "Oh, oh! Me! Call on me!" and bouncing out of his seat with the answer. The girls who blows out her friend's birthday candles because it was just too hard to wait. The child always forgetting his hat, books, lunch and everything else not attached to his body.

Validated scales (such as Conners' scale and the Child Behavior Checklist) exist to help guide the evaluation and treatment of ADHD. The questionnaires are filled out by parents, teachers, and sometimes the children themselves, about various behaviors ranging from how quickly they complete homework to how well they sleep. (I boast my own unvalidated scale: the "blood pressure cuff sign." If a child comes in my office and plays with the blood pressure cuff, I am on high alert.) We've made strides in understanding the genetics and neurobiology of ADHD in children. But a funny thing happens to children when you feed, bathe and clothe them over a decade or so ... they turn into adults.

Then what happens to their ADHD?

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Much of the time, the condition continues. Sometimes, patients have had childhood symptoms which flew under the radar until, as adults, they discovered what the problem had been all those years. Then they are told they have "adult ADHD." [Use of ADHD Drugs Increasing Rapidly Among US Adults ]

Which brings me to Dr. Zoe Goldman, the psychiatrist with adult ADHD in my psychological thriller "Little Black Lies" (Grand Central Publishing, 2015). Zoe has had ADHD her whole life. Her case may be genetic, but since she was raised by her adoptive mother, she will never know for sure. Her chaotic upbringing before her birth mother's death may have also contributed to the condition. In any case, she has ADHD and has been on multiple medications for it over the years. Now she handles her ADHD with regular psychiatry appointments and Adderall (dextroamphetamines), to rev up her dopamine levels, as well as behavioral management (e.g., exercise, calendar reminder alarms). Dr. Goldman deals with her disorder, all the while searching for the truth about her birth mother's death. ['Little Black Lies' (US 2015): Book Excerpt]

Why did I pick, of all people, a psychiatrist with ADHD as my heroine? Part of me thought back to that little girl standing proudly by her poster. She was willing to spread the word, to let people know kids with ADHD aren't "weird" or "bad." Why not help the "cause" by creating a character who demystifies this psychiatric-neurological condition? The little girl was showing the parents and students in her class that children with ADHD are normal kids. They just have issues, like everyone does. Everyone has a struggle, and this is Zoe's struggle. On a less altruistic note, I was also hoping to create a memorable, original character, who was likable, but flawed. Someone people could understand, and befriend.

I would even say ADHD has garnered a certain caché. This diagnosis means you're different, in a good way. Creative. Standing out from the crowd. One of my Facebook posts that scored the most likes was a poorly drawn cartoon figure yelling, "What do we want? A cure for ADHD! When do we want it? Squirrel!" Dare I say, ADHD has become almost hip.

Maybe this is because the symptoms are somewhat universal, much more so than with other disorders. Schizophrenia, for example, is a different story. Most people have never experienced hallucinations or paranoid delusions. But ADHD ... everyone can relate to that. I forgot three appointments last week. Am I stressed out, or do I have adult ADHD? I'm always fidgety. Could it be ADHD? In fact, while writing this article, I self-administered an online adult-ADHD quiz and scored in a range that was "highly probable for ADHD" (#dontjudge). Do I actually have ADHD based on one quiz? I doubt it. Dr. Zoe Goldman would have gotten a much higher score. There's a spectrum, and everyone falls in there somewhere.

In fact, the rates of ADHD in the United States seem to be on the rise, with a reported 11 percent of children between 4 and 17 years old diagnosed in 2011-2012. Why? The answer is unclear. It could be due to better diagnostic criterion, more awareness or possibly an unknown environmental issue compounded by genetics. (Or, as I heard a schoolteacher say, "something in the water.") We don't know. But we do know it's not going away. The etiology, or cause, of the increase in neurobehavioral disorders, including autism, is the million-dollar question, and one that will prove even more costly if the world cannot answer it, and soon. [ADHD on the Rise Among Children, New Study Says]

Dr. Zoe Goldman is not the first, nor will she be the last, protagonist with ADHD. In some ways, she represents the new normal. Words such a "special needs" and "neurodiversity" have snuck into the lexicon. Schools are bragging about personalized learning styles and inclusivity. Colleges catering to Asperger's syndrome and ADHD are popping up. More and more people have a friend, cousin, aunt or child with a diagnosis. Like any good psychiatrist, Zoe realizes the first step in solving an issue is to talk about it. And she is standing by her poster, more than ready to lead the conversation.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.