Maya Mural Reveals Ancient 'Photobomb'

An ancient Maya mural found in the Guatemalan rainforest may depict a group portrait of advisers to the Maya royalty, a new study finds.

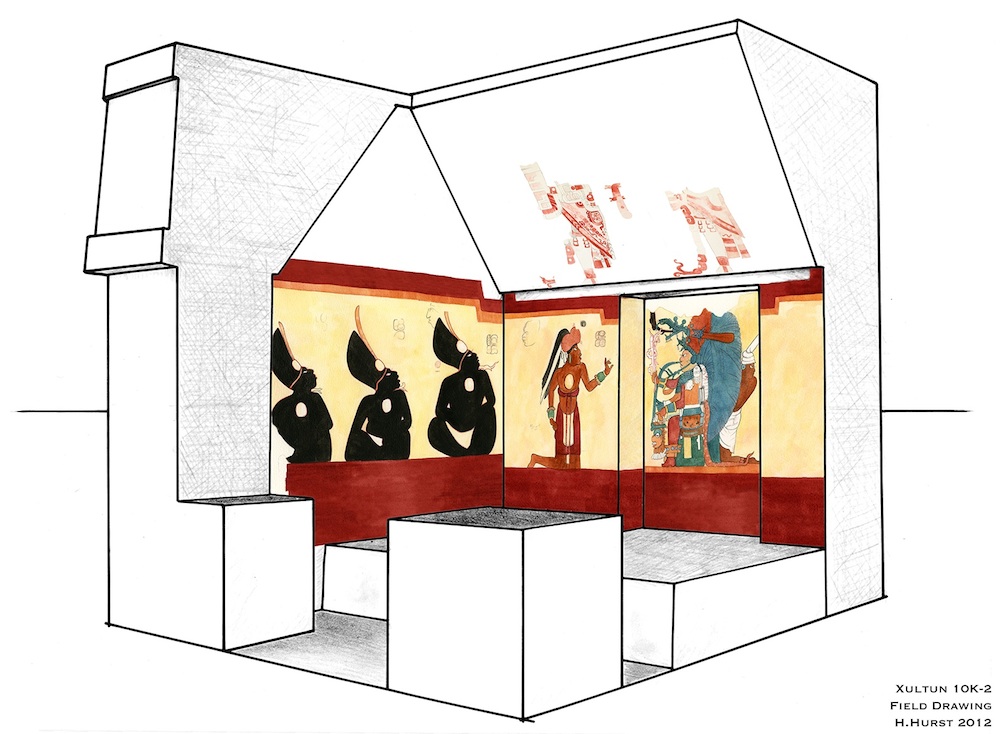

Most Maya murals depict life within the royal sphere, but the newfound mural, uncovered in the Guatemalan rainforest in 2010, shows a vibrant scene of intellectuals consulting with the royal governor, who is dressed as the Maya wind god.

Behind him, an attendant, almost hidden behind the king's massive headdress, adds a unique photobomb to the mural, said Bill Saturno, the study's lead researcher and an assistant professor of archaeology at Boston University. [See Photos of the Ancient Maya Mural]

"It's really our first good look at what scholars in the eighth-century Maya lowlands are doing," Saturno said.

The murals also provide information about a man buried beneath them. During an excavation, the archaeologists found the skeleton of a man dressed like the sages in the mural. It's possible the man once lived in the room, which later became his final resting place, Saturno said.

Archaeologists discovered the approximately 1,250-year-old mural in the ancient city of Xultun, located in the northeastern part of present-day Guatemala. During an archaeological study of Xultun, an undergraduate student inspecting an old looters' trail noticed traces of paint on an ancient wall covered by dirt.

"My assumption was that there would be very little to see," Saturno said. "Not because the Maya didn't paint murals — they did — but they don't preserve well in a tropical environment."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, the elements had been kind to the building and its treasures. The excavation uncovered a rectangular room covered with murals and a Maya calendar, the oldest known Maya dating system on record.

Mysterious obsidians

The mural is one of only two known murals in the eastern Maya lowlands that have lasted throughout the ages, the researchers said. The Xultun paintings, illustrated in vibrant red, blue, green and black pigments, cover three of the room's four walls. The fourth wall, damaged by looters, contains the door.

Saturno and his colleagues excavated past the point where the looters tunneled, and came face-to-face with "the polychrome face of a king seated with his blue-feathered headdress," Saturno said. A man kneeling before the king, labeled itz'in taaj, or "junior obsidian," faces the king in profile.

Behind the junior obsidian, on the west wall, are three men dressed in black and sitting cross-legged. One of the men is labeled ch'ok, or "youth," and another is called sakun taaj, or "senior obsidian."

It's unclear what "obsidian" means, the researchers said.

"Are they religious? Are they scholars? Is there a line between those things?" Saturno said. "They seem to be making books and painting tables on the walls."

All three men wear the same headdress with a medallion and feathery plume, a white loincloth and a medallion on their chests.

"You see these three guys dressed identically and lining up on one wall," Saturno said. "That's strange. They're clearly being represented as a unit."

The fact that they're all wearing the same uniform suggests the obsidians shared similar duties, Saturno said. Moreover, the people who filled the obsidian order probably lived in the room for a period of time, as there are dozens of texts painted on the walls. [Maya Murals: Stunning Images of King & Calendar]

Water and tree roots largely damaged the east wall, but the archaeologists still managed to find the painted remains of three individuals.

All the king's men

The mural may depict a consultation between the king and the obsidian, the researchers said. The king is dressed as a version of the wind god, holding a staff with wind symbols on it.

"Maya kings often dress up as deities in performance," Saturno said. "Essentially re-enacting events from the mythic past."

The timing of the performance was important, and the obsidian may have been advising the king about its correct date, he said. To remember meetings such as these, obsidians or artists may have painted the mural, he said.

"The mural establishes a direct relationship between a particular order, or guild, of Xultun artists and scribal-priests and their lord, and it celebrates its members’ achievement in consulting and producing work for their sovereign's reign," the researchers wrote in the study.

The king sports blue, green and orange accessories, whereas the obsidians are painted in reddish and black colors. The pigments from the king's portrait "are not common to that part of the region where it's from," Saturno said. "These are materials that are being traded in."

The painting also shows an attendant behind the king, possibly to hold up his headdress, Saturno said. "It's like a photobomb," he joked. "He's almost like, 'Do you see me here?'"

In contrast, the orange and red colors are made from local pigments, which likely helped differentiate between royal and non-royal subjects in the mural, the researchers said.

The study is "a brilliant gem of scholarship," said David Freidel, a professor of anthropology at Washington University in St. Louis, who was not involved with the study.

"This room celebrates a special group of members of the royal court of Xultun that are called obsidian, [or] taaj," Freidel said. "The obsidian people appear to be present at other sites, but we don't know much about them."

It's remarkable that the intricate mural wasn't painted at the royal residence, said Takeshi Inomata, a professor of anthropology at the University of Arizona, who wasn't involved in the study.

"This comes from the residence of a courtier, a court official," Inomata said. "This tells us about how those political organizations of Maya society were run, and then we can really get to the people who are really doing all of those things."

The study was published in the February issue of the journal Antiquity. The coauthors are Heather Hurst at Skidmore College in New York, Franco Rossi at Boston University and David Stuart at the University of Texas at Austin.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.