Human Hibernation: Snowy States Cause Longer Slumbers

On a cold and snowy day, you may want nothing more than to stay in bed until the weather's a little better.

Turns out, this may be a common sentiment — people in snowier states appear to sleep for a little longer during winter months than those in sunnier states, according to a recent analysis of data from a popular sleep tracking app.

Using the app, called Sleep Cycle, researchers surveyed data from more than 140,000 people in the United States between Jan. 1 and 31 this year.

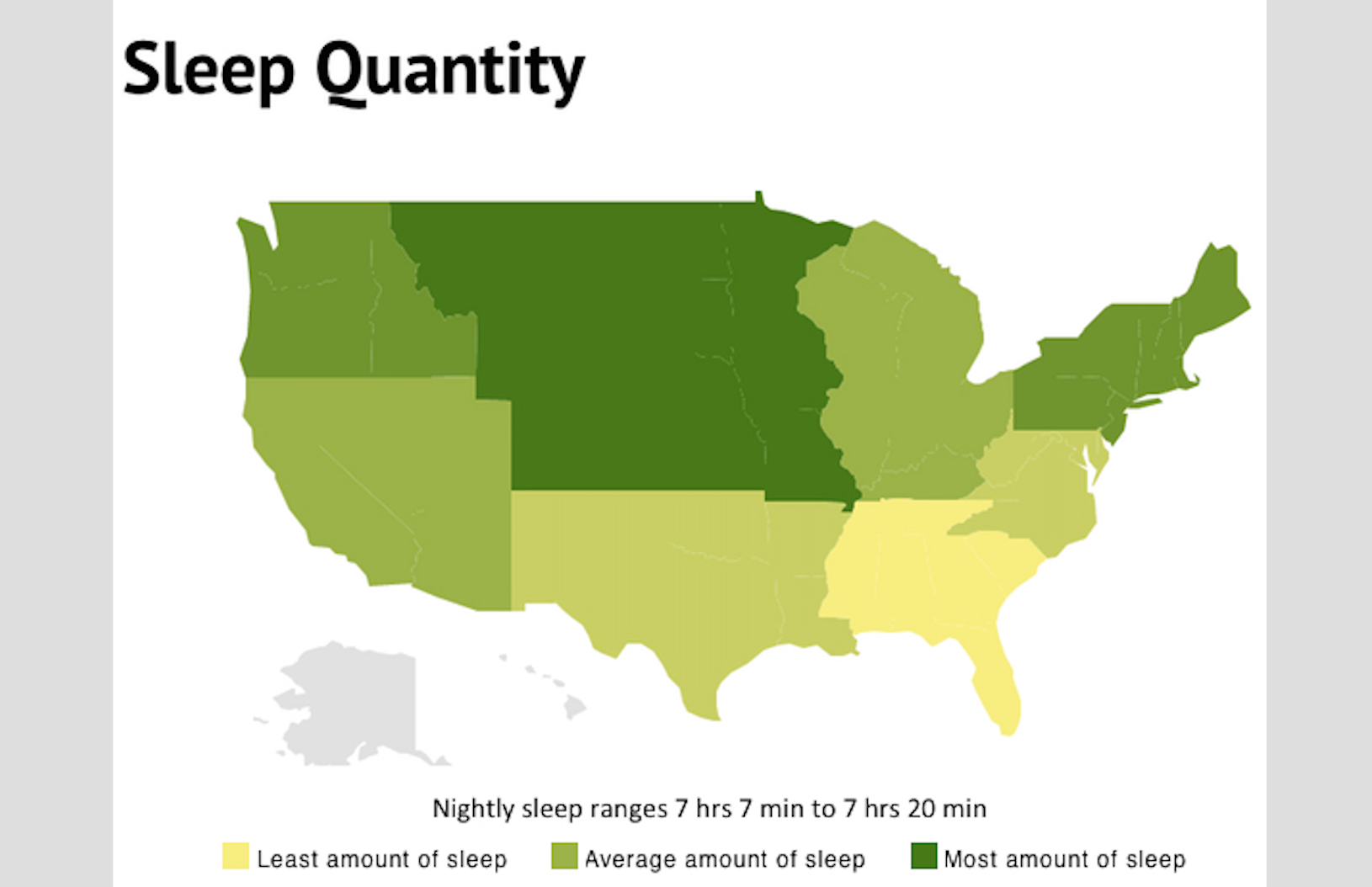

Users who live in snowy Northwestern states, including Montana, Wyoming, North Dakota and South Dakota, spent the longest time in bed — 7 hours and 20 minutes a night, on average.

That's about 13 minutes longer than the average of people who live in the Southeastern states (Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina and Florida), who spent on average 7 hours and 7 minutes in bed.

During the first half of January, people in Hawaii got the least amount sleep. There, temperatures averaged in the 70s Fahrenheit (21-26 degrees Celsius), and those using the app got about seven hours of sleep. People got the most sleep in Colorado, where users spent 7 hours and 23 minutes in bed, on average. [Turn Off to Tuck In: 5 Sleep Tips for Gadget Junkies]

Brant Hasler, a sleep expert and assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh who was not involved in the research, cautioned that the population in the new study is likely not completely representative of each state, because the researchers included only the people who use this particular sleep-tracking app.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In addition, because the study was conducted at one point in time, it cannot say whether people's sleep habits changed in the wintertime compared to the summertime.

But the finding that people sleep longer under more wintry conditions is generally consistent with what's known from previous research, Hasler said.

"Many people report that they feel tired and want to sleep more during the winter," Hasler said. This change in sleep habits is mainly due to the reduction in daylight hours in the wintertime, which affects people's internal circadian clocks and makes them want to sleep more, he said.

Places farther away from the equator see more of a change in daylight hours from summer to winter. So the amount of sleep that people need in order to feel rested "may vary depending on the time of year and where you live," Hasler said.

But should people sleep in more during the winter if they feel they need the extra rest? Hasler said that, in general, it is a good idea to accommodate one's need for sleep.

One way to do so is to go to bed earlier, or if you have flexible work hours, to start your day a little later, Hasler said.

But if you can't change when you start your day, and you have a hard time getting up in the morning, another option is to try to boost alertness in the morning with a bright light, or "light box", Hasler said.

Such light boxes, which generally cost $100 or less, were originally developed to help people with seasonal affective disorder (SAD), a type of depression that's thought to be triggered by a reduction in daylight in the winter. But light boxes may be useful for people without SAD, too. In fact, Hasler said he uses one himself during the winter.

People should expose themselves to the bright light as soon as possible when they wake up in the morning, for 30 minutes to an hour, Hasler said. Those who can't fit that light exposure in before going to work, Hasler said, might use a light box at their desks in the morning, as he does.

Light-box therapy is generally very safe, although some people may experience side effects, including individuals who are prone to migraines, or who have bipolar disorder, Hasler said. It's worth talking to your doctor about potential remedies if you are having trouble sleeping in the winter, he said.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.