Editor's Note: This story was updated at 11 a.m. E.T.

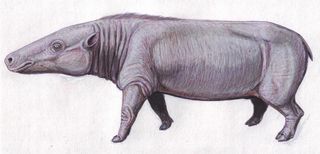

The first hippos may have been about the size of overgrown sheep.

Fossils from an ancient ancestor to hippos, part of a family of creatures known as anthracotheres, have been unearthed in a rock bed in Kenya. The new finds suggest the ancient water-babies weighed just a few hundred pounds and looked like shrunken versions of the portly mammals found in Africa today.

"They are slender hippos, very thin hippos," said study co-author Fabrice Lihoreau, a paleontologist at the University of Montpellier in France.

What's more, the new study reveals the hippo ancestor, Epirigenys lokonensis, first evolved in Africa. [See Images of the Hippo Ancestor and Its Modern-Day Descendants]

Ancient group

Genetic data suggests that hippos and whales shared a common ancestor about 53 million years ago, while the family of hippopotamidae emerged just 15 million years ago. In between these points, the fossil record is incredibly scarce, Lihoreau said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Many scientists believed the ancestor to hippos came from a family of extinct, semi-aquatic mammals, the anthracotheres, which first emerged about 40 million years ago. These ancient beasts once roamed throughout the world, from North America to Asia. But the ancestor to hippos was never found.

Lihoreau and his colleagues were looking through the collections at the Nairobi Museum in Kenya when they found an intriguing jaw from an anthracothere. The fossil had come from the Turkana Basin, a region of Kenya famous for fossils from the Cretaceous Period to the present day, including those of ancient Homo erectus and Homo habilis. The area where the fossil jaw was found in the basin, called the Turkana Grits, was teeming with fossils of crocodiles and other aquatic animals from about 28 million years ago, but the rock was too hard to dig.

However, while scouting around, the researchers discovered a small spot called Lokone Hill where the rock was softer, and could be eaten away by acid, making it easy to excavate fossils.

Characteristic teeth

The team uncovered several teeth from a new anthracothere species at Lokone Hill, including molars and incisors. Similar to teeth in modern-day hippos, the molars showed a distinctive three-leaf pattern that looks a bit like a maple leaf. The team named the new species Epirigenys lokonensis, which roughly translates to "original hippo from Lokone," Lihoreau said.

The molar pattern revealed that E. lokonensis was a direct ancestor to hippos. (Because mammal teeth are so unique, patterns on the molars can serve as a kind of species fingerprint, enabling paleontologists to tie ancient creatures to their modern descendants.)

E. lokonensis was probably just 220 pounds (100 kg), much smaller than the lumbering 2- or 3-ton hippos of today. But just like today's pudgy creatures, these animals lived in the water.

The findings also confirm that hippopotami first evolved in Africa.

"When you do a safari, you want to see a lion and you want to see an antelope, but these animals come from Asia " Lihoreau told Live Science. "They are not really African mammals. This is really an African mammal."

The new species was described today (Feb. 24) in the journal Nature Communications.

Editor's Note: This story was updated to correct the spelling of anthracothere and to note that Homo habilis, not Neanderthals, were found in the Turkana Basin.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Most Popular