Triassic Tracks: Gallery of Ancient Reptiles' Footprints

When ancient reptiles meandered into the Triassic oceans for lunch, their claws dug into the mud and they sometimes trailed their bodies across the seafloor, leaving well-preserved tracks. Tracy Thomson, a graduate student in the Department of Earth Sciences at the University of California, Riverside, spent two summers in Utah’s desert uncovering these tracks. The following images, courtesy of Thomson, are a few examples of perfectly preserved Triassic tracks. [Read full story about these ancient footprints]

Drifting in the current

Thomson stands next to a site called Chimney Rock in Capitol Reef National Park. It shows the track of a swimming animal that drifted diagonally in a current.

Light weight

Here's a close-up of two swim tracks from the surface in the previous photo. The reptile's claws left only swipe marks with no discernible heel impression, which suggests the animal was buoyant in the water.

Buoyancy

A second track surface at Chimney Rock.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Leaving "z" shapes in the sand

Here's a close-up of the second track surface showing an individual swim track with a "z" shape. This type of swim track is unique to the early Triassic period, the researchers said. It's the result of a single claw entering the soil from the top, moving down, then up to the right, then down again, before finally exiting the soil upwards.

Friends dine together

Here's the underbelly of a ledge covered with swim tracks at a site from Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. The track surfaces at some localities can be quite dense with swim tracks, the researchers said.

Pushing away

A swim track from a site called Desert Flower in Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. This is the created by the animal digging into the soil and then pushing itself forward and withdrawing its claws.

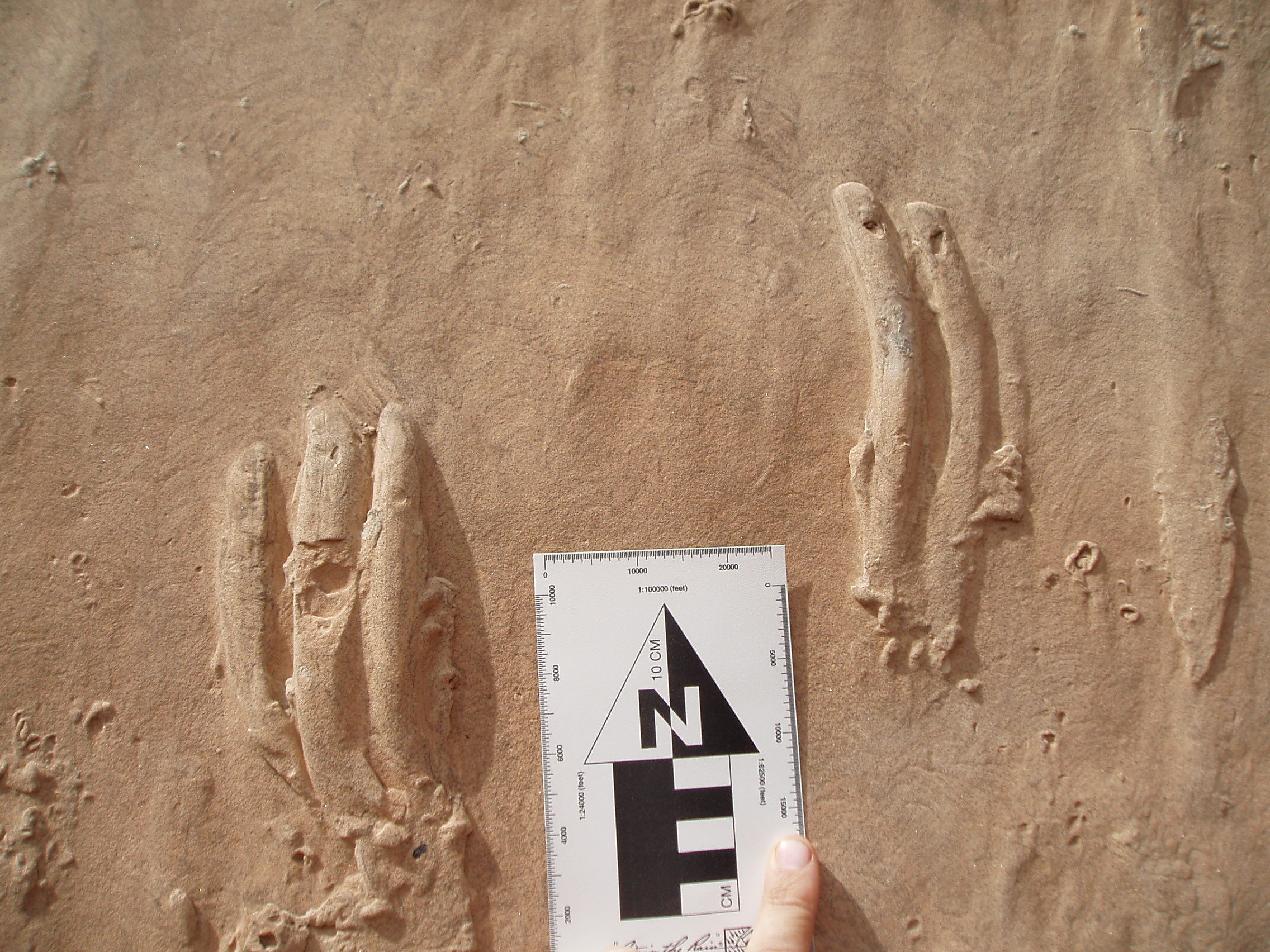

Dragging your feet

Thomson collected this slab from a site called Little Dragon in Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. It's currently held in a collection at the Utah Natural History Museum. It shows thin, wavy scratch traces going from right to left and terminating at a footprint. Thomson thinks this is the result of the animal dragging its claws as it floated along and then putting both hind feet down to push off and then float again. Crocodiles sometimes use this method today to move along the bottom of a pond or river.

Follow Shannon Hall on Twitter @ShannonWHall. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus