Old Medicines Give New Hope for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (Essay)

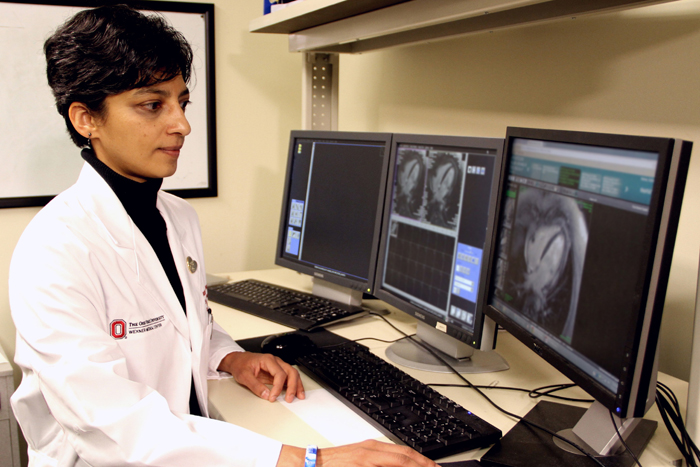

Dr. Subha Raman, cardiologist at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, contributed this article to Live Science’s Expert Voices: Op-ed & Insights.

People with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, or DMD, have a genetic disorder where the body does not produce dystrophin, a protein that helps keep muscle cells intact — as a result, the condition causes muscles to rapidly break down and weaken. Because the muscle in the heart is damaged, a majority of DMD patients suffer cardiac failure after only surviving into their 20s or early 30s.

Now, in a study published in The Lancet Neurology, my colleagues and I have found new cause for hope. We found that a pair of cardiac drugs that have been on the market for years — when used together — appear to be particularly effective at slowing cardiac damage.

Old medicines, new treatment

As a cardiologist and professor at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, I partnered with a team of DMD experts from around the nation in a clinical trial that tested the combination of eplerenone (an aldosterone antagonist that serves as a potassium-sparing diuretic) and either a angiotensin-converting-enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB). ACE inhibitors and ARBs help relax the blood vessels and make it easier for the heart to pump blood. [Beyond Vegetables and Exercise: 5 Surprising Ways to Be Heart Healthy ]

We based this trial on our previous lab findings showing this combination of medicines reduced muscle damage and preserved heart function in mice with DMD. In this human trial, we enrolled 42 boys with DMD who showed evidence of early heart muscle damage by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. (Located on the X chromosome, DMD predominantly affects males, because females have two X chromosome copies and rarely show signs of the disease.)

In the double-blind study, the boys were randomized to receive one daily 25 milligram pill of placebo or eplerenone for one year. All patients continued to receive ACE or ARB and remained under the care of their physician.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

After 12 months, the group getting the eplerenone treatment reported significantly less decline in left ventricular function than the patients on the placebo. The results indicated at least six months of therapy was needed to realize that benefit.

Early prevention, longer lives

The findings are encouraging. We believe this research offers evidence that supports the early use of these readily available medications.

We know warning signs show up in DMD patients well before complications like congestive heart failure and arrhythmias occur. By impacting the earliest detectable change in heart function, we expect to see even greater benefits with longer-term follow-up of these patients. Slowing the progression of heart disease should translate into longer lives and improved quality of life for affected individuals and their families.

Our research was inspired by 26-year-old Ryan Ballou of Pittsburgh, Penn. He’s a young man with DMD who, along with his father, started BallouSkies to raise awareness and funding for research of heart disease in muscular dystrophy patients. BallouSkies was the primary financial supporter of this clinical study — this research progressed much faster thanks to their support — with additional support provided by the Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy, the U.S. National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

Our team involved researchers from Nationwide Children's Hospital in Columbus, The Christ Hospital Heart and Vascular Center and Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center in Ohio, the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) and the University of Maryland — and our next trial to build upon these results is already underway.

That trial will test the benefit of combination heart-failure medicines for patients with DMD without requiring evidence of baseline heart muscle damage to start treatment. We will enroll patients at four U.S. sites: Ohio State's Wexner Medical Center/Nationwide Children's Hospital, UCLA, the University of Colorado and the University of Utah.

While there is still no cure for DMD, scientific discoveries are leading researchers like my team and our peers to promising treatments. Medical knowledge of neuromuscular disease is broadening, and children and adults with Duchenne muscular dystrophy are living longer, fuller lives.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.