Photos: Earliest Known Human Fossils Discovered

Scientists have discovered 2.8-million-year-old fossils of what may be a new human species in Ethiopia. The findings suggest humans arose a half million years earlier than previously thought. Here are images of the newfound fossils and the dig site. [Read the full story on the newfound early human fossils]

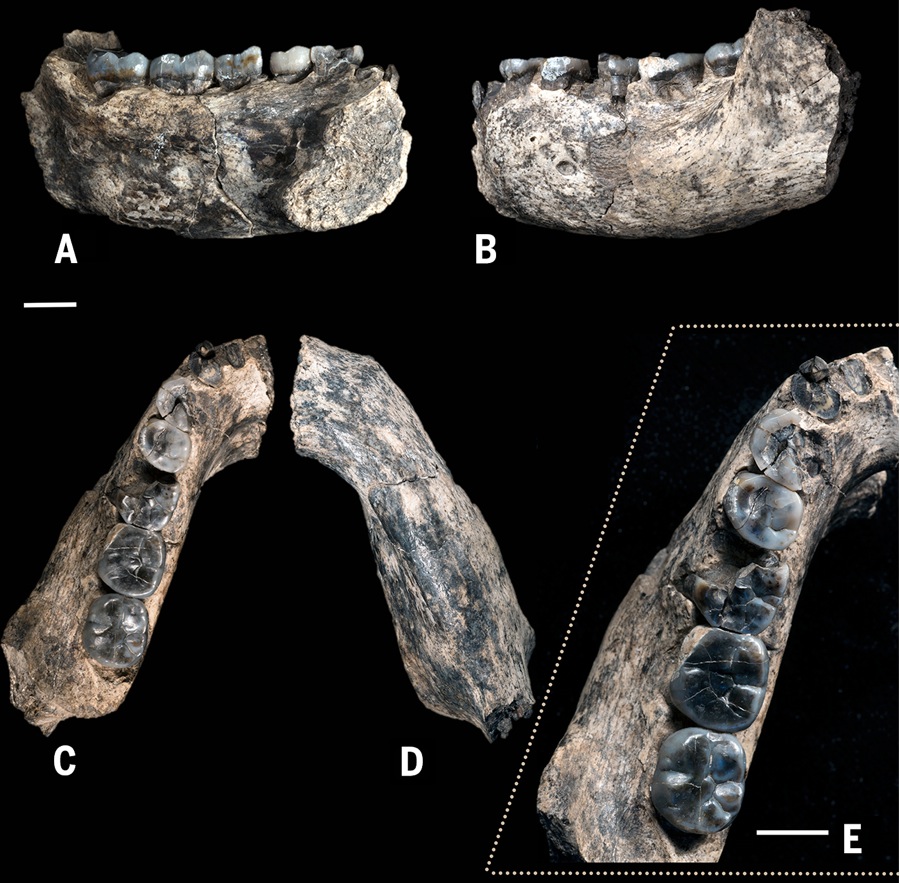

Partial mandible

Geologists work in the field at the Ledi-Geraru site in Ethiopia, where they discovered a partial mandible, with five of its teeth intact, belonging to an individual in the genus Homo. (Photo credit: Brian Villmoare)

Sieving sand

Scientists sieve through sand at the Ledi-Geraru site at the Afar Regional State in Ethiopia, where they discovered the Homo mandible, known as LD 350-1. (Photo credit: Brian Villmoare)

Mixed traits

A close-up of the LD 350-1 mandible unearthed from the Ledi-Geraru research area. Scientists found the mandible combines a mix of primitive traits seen in the more apelike Australopithecus species and traits found in more human early Homo species. The new finding is detailed online today (March 4) in the journal Science. (Photo credit: William Kimbel)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

New human species?

Another close-up view of the Homo mandible, shown just steps from where Arizona State University graduate student Chalachew Seyoum from Ethiopia spotted it. The scientists involved in the discovery aren't sure if the fossil belongs to a new species or to a known, extinct human species, such as Homo habilis. They plan to learn more about the fossil before making that decision and giving it a name. (Photo credit: Kaye Reed)

Hippo jaws

The mandible of a hippo was also discovered at the Ledi-Geraru site. The mandible is still in the ground there, said study researcher Brian Villmoare of the University of Nevada Las Vegas. (Photo credit: Brian Villmoare)

Camels!

A camel caravan walks through the excavation site in the Afar region where researchers dug up a partial mandible from a potentially new Homo species. The researchers dated the fossil by looking at the ages of the layers of volcanic ash above and below it. (Photo credit: Brian Villmoare)

Minimum age

Another view of a camel caravan as the animals move across the so-called Lee Adoyta region in the Ledi-Geraru research site near where researchers discovered the early Homo mandible. The hills behind the camels reveal sediments that are younger than 2.67 million year old, providing a minimum age for the partial mandible dubbed LD 350-1, say the scientists. (Photo credit: Erin DiMaggio, Penn State)

More fieldwork

Chris Campisano, of Arizona State University, samples a tuff in the Ledi-Geraru project area in Ethiopia with support from Sabudo Boraru. (Photo credit: J Ramón Arrowsmith)

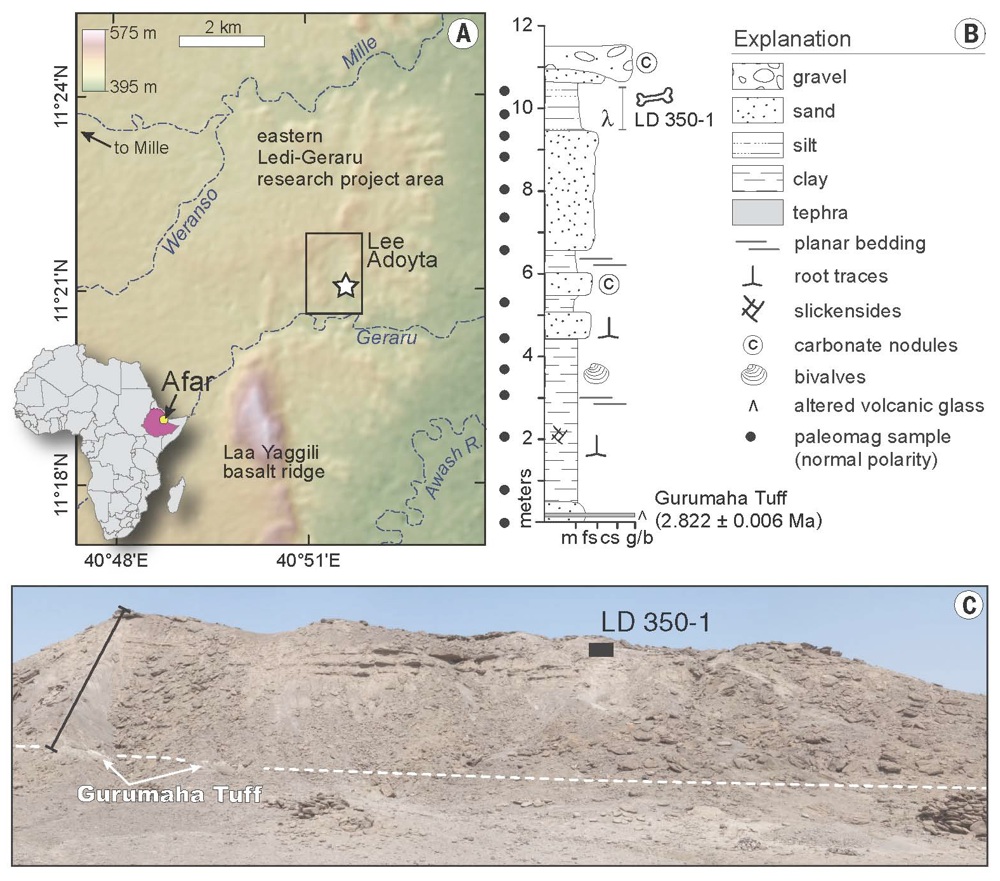

Ledi-Geraru geography

Here, the Ledi-Geraru site, including geography and geological stratification, where scientists found the Homo fossil jaw dating to 2.8 million years ago. Until now, the earliest valid fossil evidence of a Homo species dated to about 2.3 million or 2.4 million years ago, the researchers noted. (Credit: Villmoare et al.)

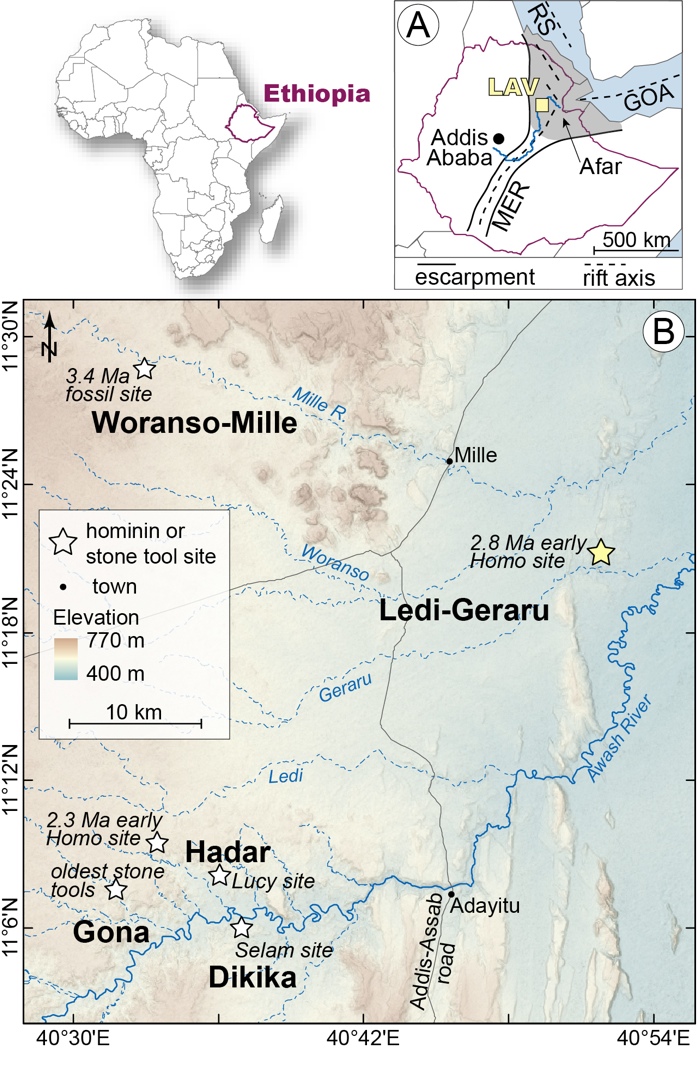

Fossil map

A detailed map of the location of the Ledi-Geraru site, where the Homo mandible was discovered, in reference to other important fossil sites in Ethiopia. (Image Credit: Erin DiMaggio)

Homo habilis?

There's a chance the mandible belonged to an individual of the species Homo habilis, as a report also out today (March 4) suggests a key fossil of that species also is a mix of both primitive and more advanced traits. Shown here, a partial lower jaw, bones of the braincase and hand bones from a Homo habilis called the Olduvai Hominid 7 (OH 7). (Photo credit: John Reader)

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.