Snowflakes Aren't Even Like Themselves, New 3D Images Reveal

Julia Gureck, multimedia intern in Office of Legislative and Public Affairs at the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

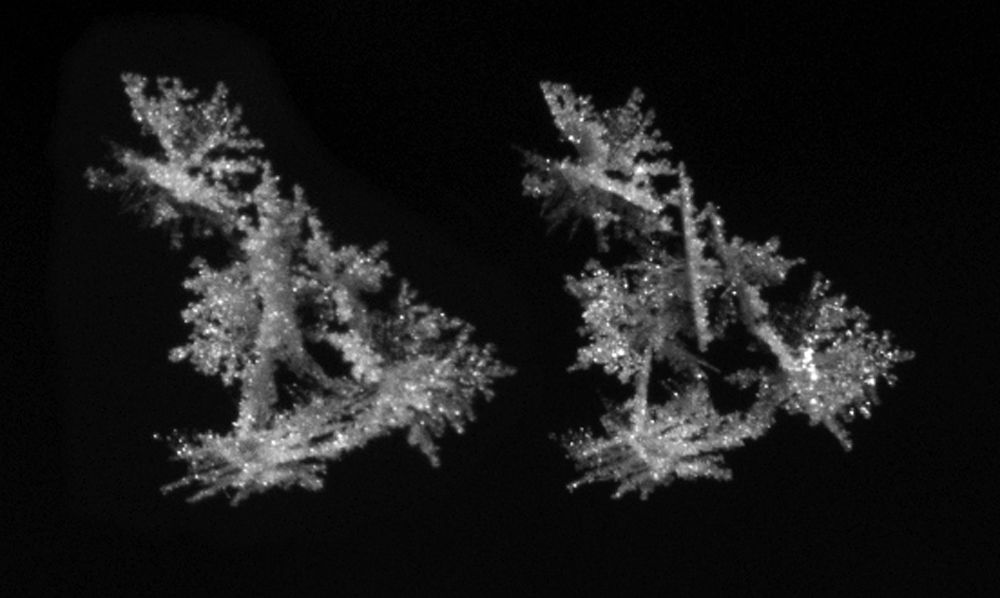

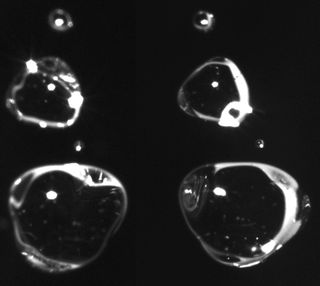

You've heard that no two snowflakes are alike, but it gets even more complicated: The two sides of the same snowflake aren't even alike. Now, researchers using a cutting-edge 3D camera are able to use these imperfections to update estimates of road slickness and other storm impacts, improving winter weather warnings in real time and saving lives.

The popular image of a perfectly symmetrical, six-sided snowflake originated with Wilson Bentley in 1885. Only 20 years old, Bentley came up with the idea to connect a microscope and a camera to photograph the ice crystals of snowflakes. Bentley’s photographs gave the public an appreciation for the beauty of snowflakes. [Watch the video to learn more about the PWI, the history of snowflakes and how scientists' understanding of these crystals has evolved.]

Now, with a recent NSF grant, University of Utah researchers Cale Fallgatter and Tim Garrett developed a special camera with a built-in computer to capture images of snowflakes in midair. The researchers call the high-speed system the Present Weather Imager (PWI). [Capturing Falling Snow, One Flake at a Time (Gallery)]

This imager enables the researchers to see a single snowflake as small as 100 micrometers across — the diameter of a human hair — in perfect detail and in three dimensions.

Weather prediction, one snowflake at a time

These crystal-clear images allow Fallgatter and Garrett to determine the exact size and shape of snowflakes, as well as the speed at which they fall. By combining this data, the researchers can tell exactly what type of precipitation is falling, with greater accuracy than ever before. If they waited for the flakes to hit the ground, it would be too late — the data would be lost.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

What exactly does all of this have to do with your weather forecast?

Meteorologists issue weather warnings based on the same kind of data the PWI collects. Certain types of snow, for example, make roads slicker than others. With more accurate information about what's falling from the sky, meteorologists can issue better weather warnings on the ground, which can save lives by preventing accidents.

According to the U.S. Department of Transportation, weather causes roughly 1.3 million traffic accidents every year. Better precipitation data could help lower that number. If the PWI can tell officials what type of precipitation is falling, local transportation departments could choose the appropriate preparation and treatment for roads, and close dangerous ones.

"Meteorologists are getting these forecasts wrong because they're using formulas for predicting snowflake shape and fall speed that are based on measurements from the 1970s," Garrett said in a recent interview with the Utah Adventure Journal. "What's been holding them back is there hasn't been a formula available to make more accurate predictions." [Cold Weather Fun: Boiling Water Turns to Ice Crystals ]

To address that shortcoming, Garrett and Fallgatter's snowflake images can help build better formulas for models that predict snowfall. Will the snow be light and fluffy or the packing kind? Will it stick to the roads or disappear on contact? Will it turn to rain or sleet on the way down? These are all questions snowflakes can answer thanks to the PWI.

Weather still remains difficult to model and predict, but continuing to develop tools like the PWI can help reduce uncertainty and increase safety for those affected by winter storm systems.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.