After Much Ado, El Niño Officially Declared

Just when everyone had pretty much written it off, the El Niño event that has been nearly a year in the offing finally emerged in February and could last through the spring and summer, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration announced Thursday.

This isn’t the blockbuster, 1998 repeat El Niño many anticipated when the first hints of an impending event emerged about a year ago. This El Niño has just crept across the official threshold, so it won’t be a strong event.

“We’re basically declaring El Niño,” NOAA forecaster Michelle L’Heureux said. “It’s unfortunate we can’t declare a weak El Niño.”

In part because of its weakness, as well as its unusual timing, the El Niño isn’t expected to have much impact on U.S. weather patterns, nor bring much relief for drought-stricken California.

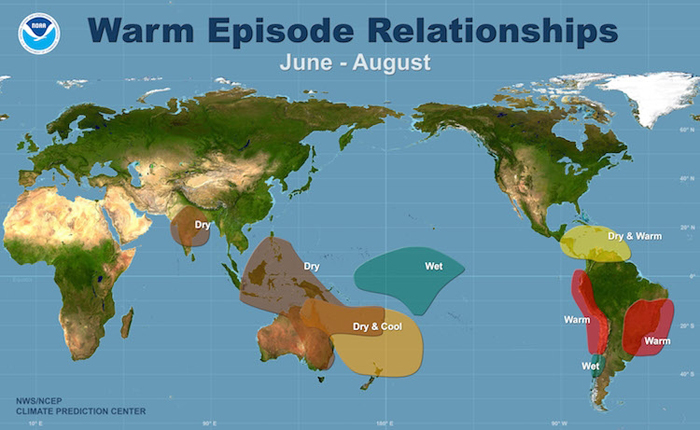

But forecasters say it could nudge weather patterns in other areas of the globe, especially if it persists or intensifies, and could boost global temperatures — following a 2014 that was already the hottest year on record.

“It does tilt the odds toward warmth,” L’Heureux said.

The Difference a Year Makes

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Forecasters with NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center and the International Research Institute for Climate and Society (IRI) at Columbia University first raised the alert early last year that an El Niño might be taking shape. They based it on a subsurface plume of warm water, called a Kelvin wave, surging from west to east across the tropical Pacific. (It was this large plume that drew comparisons to the monster El Niño of 1998, which caused deluges and flooding in many parts of the world and significantly amped up global temperatures. 1998 is still the only 20th century year among the top 10 warmest.)

Why Do We Care So Much About El Niño? Global Warming May Worsen Effects of El Niño, La Niña Events A Broken Record: 2014 Hottest Year

An El Niño is marked by unusually warm waters over the central and eastern parts of this basin. The CPC officially considers it an event when the sea surface temperatures in a key region of the ocean reach at least 0.5°C, or about 1°F, warmer than average.

Multiple Kelvin waves have pulsed across the ocean basin in recent months and ocean temperatures have repeatedly been warm enough in that region to qualify as an El Niño.

But ocean temperatures alone don’t define an El Niño; CPC forecasters also look for the corresponding shifts in atmospheric patterns, namely a weakening of the typical east-to-west trade winds over the region. Those altered winds can affect weather around the globe. That’s why they are watched so carefully month after month.

A year after that first sign of an impending El Niño surged across the ocean, another Kelvin wave is making its way across the basin. Only this time, the ocean is already much warmer and most importantly, the atmosphere seems to have finally gotten the memo, with the trade winds weakening.

The coupling between ocean and atmosphere isn’t following the usual script, and the typical shifts in rain patterns haven’t emerged. But L’Heureux noted the rarity of any response from the atmosphere at this time of year. In spring, she said, it is harder for the ocean and atmosphere “to essentially see each other.”

“We’re fairly amazed,” she said.

Spring and Summer

This late winter emergence of the El Niño means that the hallmark U.S. impacts — wet and cool conditions across the southern U.S. — won’t happen.

“Over us [the impact] becomes very, very muted” in spring, L’Heureux said.

Forecasters believe the current Kelvin wave and the already warmer ocean temperatures, signal that the El Niño is going to persist, which was another factor in officially declaring an event.

The CPC forecasts a 50 to 60 percent chance that the El Niño will chug along through the spring and summer. If it does, it could tamp down the Atlantic hurricane season and juice the season in the eastern Pacific, as many said it did last summer, before the El Niño was official.

That official designation has already spurred much debate in the climate community, since the ocean was warm enough through much of 2014 to qualify as an El Niño.

“I’m sure it’s going to be discussed quite a bit,” L’Heureux said. [View graphic of 27 years of above-average temperatures]

But whether or not those warm oceans meant an El Niño was in place, they, along with warm waters in other ocean basins, helped elevate global surface temperatures in 2014, leading to the warmest year on record.

Whether that could happen again in 2015 remains to be seen, though the ocean has a strong temperature memory and doesn’t respond to changes very quickly. So that warmth is likely to hang on, or even rise.

“If the El Niño intensifies, it may have a greater impact on the global temperatures, as observed from past events,” Jessica Blunden, a climate scientist with ERT, Inc., at the NOAA’s National Climatic Data Center, said in an email. “But for now we are in a wait and see mode.”

You May Also Like: Arctic Sea Ice Is Getting Thinner, Faster Solar Energy Jobs Growing By Leaps and Bounds Global Warming Upped Heat Driving California’s Drought Climate Change a ‘Contributing Factor’ in Syrian Conflict

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.