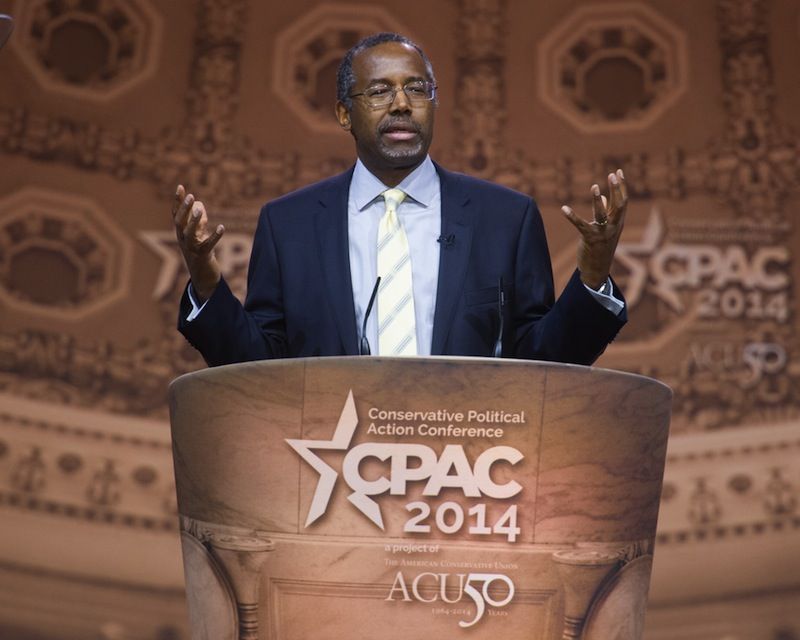

Ben Carson, a retired neurosurgeon and presidential hopeful, recently apologized for a statement in which he said being gay is "absolutely" a choice.

In an interview on CNN, the potential 2016 Republican presidential candidate commented that "a lot of people who go into prison, go into prison straight, and when they come out they're gay, so did something happen while they were in there? Ask yourself that question."

Since then, he has apologized for the divisiveness of his comments, but hasn't backed down from the notion that being gay is something people choose.

Most scientists would disagree. Years of research suggest that people can't change their sexual orientation because they want to, and that trying can cause mental anguish. What's more, some studies suggest that being gay may have a genetic or biological basis. [5 Myths About Gay People Debunked]

Biological origins

Humans aren't the only species that has same-sex pairings. For instance, female Japanese macaques may sometimes participate in energetic sexual stimulation. Lions, chimpanzees, bison and dolphins have also been spotted in same-sex pairings. And nearly 130 bird species have been observed engaging in sexual activities with same-sex partners.

While the evolutionary purpose of this behavior is not clear, the fact that animals routinely exhibit same-sex behavior belies the notion that gay sex is a modern human innovation.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

No studies have found specific "gay genes" that reliably make someone gay. But some genes may make being gay likelier. For instance, a 2014 study in the journal Psychological Medicine showed that a gene on the X chromosome (one of the sex chromosomes) called Xq28 and a gene on chromosome 8 seem to be found in higher prevalence in men who are gay. That study, involving more than 400 pairs of gay brothers, followed the 1993 report by geneticist Dean Hamer suggesting the existence of a "gay gene." Other research has found that being gay or lesbian tends to run in families. It's also more likely for two identical twins, who share all of their genes, to both be gay than it is for two fraternal twins, who share just half of their genes, to both be homosexual. Those studies also suggest that genes seemed to have a greater influence on the sexual orientation of male versus female identical twins.

A 2012 study proposed that epigenetic changes, or alterations in marks on DNA that turn certain genes on and off, may play a role in homosexuality. This type of gene regulation isn't as stable as DNA, and can be switched on and off by environmental factors or conditions in the womb during prenatal development. But this so-called epigenome can also be passed on from generation to generation, which would explain why being gay seems to run in families, even when a single gene can't be pinpointed.

How such gay genes get passed down from generation to generation has puzzled scientists, given that gay couples cannot reproduce. One study found that gay men are biologically predisposed to help care for their nieces and nephews. Essentially, these gay uncles are helping their relatives to reproduce. "Kin therefore pass on more of the genes which they would share with their homosexual relatives," said evolutionary psychologist Paul Vasey of the University of Lethbridge in Canada, in a past Live Science article.

Orientation change

If being gay is truly a choice, then people who attempt to change their orientation should be able to do so. But most people who are gay describe it as a deeply ingrained attraction that can't simply be shut off or redirected.

On that, studies are clear. Gay conversion therapy is ineffective, several studies have found, and the American Psychological Association now says such treatment is harmful and can worsen feelings of self-hatred.

For men, studies suggest that orientation is fixed by the time the individual reaches puberty. Women show greater levels of "erotic plasticity," meaning their levels of attraction are more significantly shaped by culture, experience and love than is the case for men. However, even women who switch from gay to straight lifestyles don't stop being attracted to women, according to a 2012 study in the journal Archives of Sexual Behavior.

Those results suggest that while people can change their behavior, they aren't really changing their basic sexual attraction.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Most Popular