Photos: Ancient Egyptian Tax Receipt & Other Texts

Several ancient and medieval texts at McGill University Library and Archives, in Montreal, Canada, are in the process of being deciphered and published by Brice Jones, a PhD student at Concordia University. Until now the texts had not been studied and few knew of their existence. One of the most interesting texts is a receipt for a huge land-transfer tax, written on a piece of pottery. Check out these photos of the ancient Egyptian tax receipt and other texts. [Read full story about the ancient tax bill]

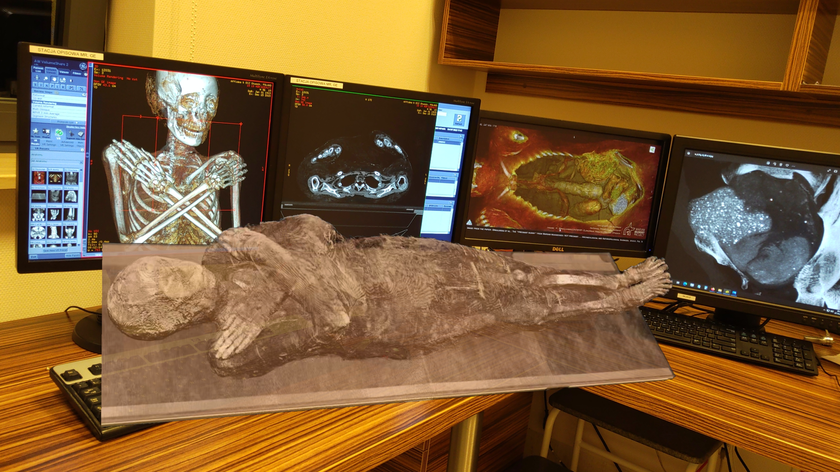

Tax day

This ancient Egyptian tax receipt is for 75 "talents" (a unit of currency), with an added 15-talent charge. To put this number into perspective, just one talent was worth 6,000 drachma, and 90 talents was worth 540,000 drachma. The date on the receipt corresponds to July 22, 98 B.C., and a worker at this time may have only made 18,000 drachma annually. It may have taken 13,500 coins, weighing more than 220 pounds (100 kilograms), to pay this tax. (Credit: Rare Books and Special Collections, McGill University Library and Archives)

An ancient leader

The tax bill dates to the reign of Ptolemy X, a pharaoh who fought against his brother for the throne. Ancient writers claim that he murdered his own mother in 101 B.C. so he wouldn’t have to share power with her. Modern-day historians doubt the tale. In 89 B.C., Ptolemy X's own army turned against him and he was killed the following year. This bust of Ptolemy X is displayed in the Louvre Museum. (Photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen, released into public domain, courtesy Wikimedia)

An ancient city

The tax receipt said that the 90 talents were paid at a public bank in a city called Diospolis Magna (the city is also known as Luxor or Thebes). This city was one of the most important in southern Egypt and contains a number of important sites in its surrounding area, including Karnak Temple. (Credit: Leonid Andronov/Shutterstock)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

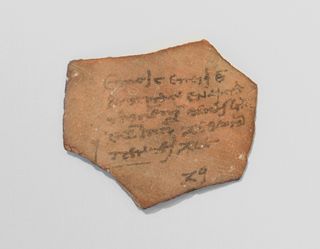

Burial information

This image shows another of the newly translated texts from McGill University. It shows a mummy label, written in Greek, which would have been worn on the neck of a mummy being transported to the burial site. Brice Jones, a PhD student at Concordia University, says the tag is from a woman named Saaremephis (possibly a misspelling) and also names her father, Heron, and the name of the city where she lived, Panopolis, which is located in southern Egypt. The tag probably dates to between the first and third centuries A.D. (Credit: Rare Books and Special Collections, McGill University Library and Archives)

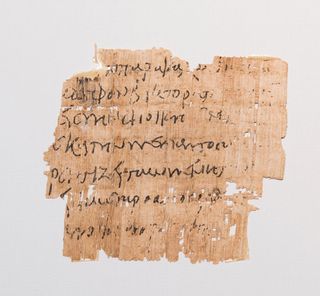

Bits and pieces

This fragmentary letter, written in Greek and possibly dating to the fourth century A.D., is also being deciphered. Jones says it appears to discuss financial matters and refers to a five-day work period, perhaps associated with dyke work, which was something that was frequently done in ancient Egypt. The text may have been written by a Christian, as it names a "brother Viktor" (the word "brother" was commonly used in the ancient world between Christians) and uses the phrase "care for the poor" (something commonly seen in Christian literature, including the Gospel of John). (Credit: Rare Books and Special Collections, McGill University Library and Archives)

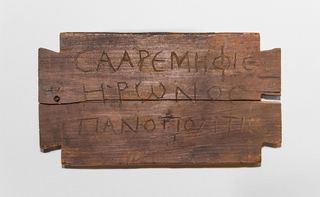

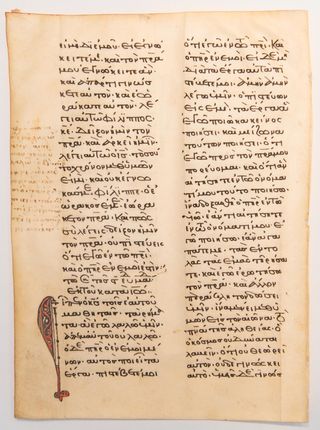

Scrap of history

Another text being studied is this lectionary, containing passages from the Gospels of Luke and John. It dates to the 12th century A.D. and may not be from Egypt. Jones found that the text is from a codex (book) that is now at the University of Chicago's Goodspeed Manuscript Collection. How it originally came apart from the rest of the codex is currently unknown. Jones says the page is "extremely well-preserved" and is "absolutely beautiful in terms of the layout." (Credit: Rare Books and Special Collections, McGill University Library and Archives)

Exciting finds

Additional texts have recently been found in a drawer at the Redpath Museum at McGill University. They include papyri written in Demotic, an Egyptian language, and fragments from the Book of the Dead, a series of spells that helped the deceased navigate their way through the afterlife. An image of part of the Redpath Museum is seen here. (Photo by Idej Elixe, Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported, courtesy Wikimedia)

Records of history

Many records indicate that all the newly deciphered texts at McGill University Library and Archives, and about half the material recently found at the Redpath Museum, were purchased by the university in the 1930's from Erik von Scherling, a Swedish antiquities dealer who sold ancient and medieval texts to institutions and collectors all over the world.

The remainder of the Egyptian texts in the Redpath Museum came from H. I. Bell, a scholar at the British Museum, who in the 1920's ran a syndicate that saw member institutions purchase papyri from him. Ultimately, von Scherling and Bell got their material from Maurice Nahman, who operated in Cairo in the 1920s and 1930s. "In the '20s and '30s he was the go-to guy for all of this stuff," Jones said.

This image shows part of McGill University. (Credit: Steve Rosset/Shutterstock)

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.