A package that was sent to the White House and tested positive for traces of cyanide likely would not have harmed anyone, scientists say.

The package had a "presumptive positive for cyanide," though it tested negative for other hazardous biological agents, The New York Times reported based on a statement from the Secret Service.

Though cyanide is a deadly poison, this particular attack was unlikely to have sickened anyone, said Hamish de Bretton-Gordon, a chemical-weapons expert with SecureBio, a chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear (CBRN) security firm based in the United Kingdom.

That's because the form the cyanide likely came in — a white, powdery substance called sodium cyanide — typically must be ingested to cause harm, de Bretton-Gordon said.

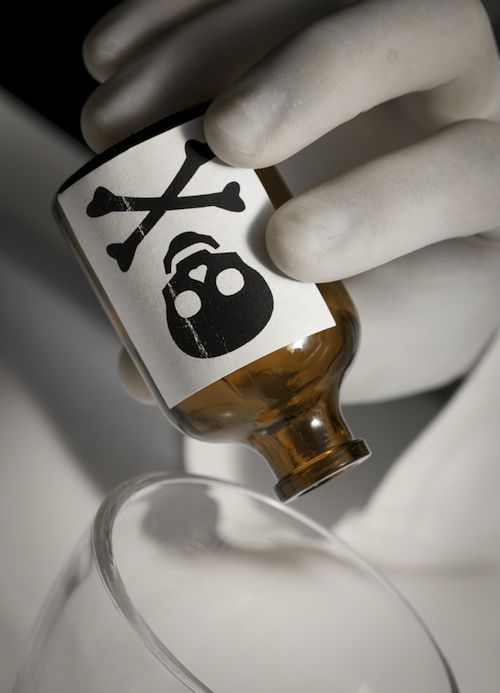

People handling mail at the White House probably wear gloves and follow strict protocols when coming into contact with packages, so they would be unlikely to have the necessary exposure to cause harm, he added. [In Photos: The Power of Poison Through Time]

Ancient poison

Cyanide is one of the oldest known poisons. The compound is found throughout nature in small concentrations, in everything from poisonous millipedes and cyanobacteria to peach pits and apple seeds.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Though people have known for millennia that bitter almonds, cherry laurel leaves and cassava contain a poisonous element, it wasn't until the 1780s that Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele isolated the deadly compound, in a synthetic dye called Prussian blue.

Cyanide can be a gas, called hydrogen cyanide, or a solid, such as potassium or sodium cyanide.

In both forms, it works the same way.

"It prevents the blood [from] carrying oxygen, which kills you very quickly," de Bretton-Gordon told Live Science.

Since its discovery, cyanide has had a long and gruesome history.

In World War II, it was the key ingredient in the infamous poison Zyklon B, which the Nazis used to exterminate millions of Jews in gas chambers in concentration camps. More recently, "we've seen attempts, probably by Islamic State, to poison people with cyanide in Syria," de Bretton-Gordon said.

Though groups, including al-Qaida, have tried to turn cyanide into a chemical weapon, cyanide has a fatal flaw as a weapon of mass destruction, according to de Bretton-Gordon. Unlike the nerve gas sarin, or mustard or chlorine gas (which was used in World War I), cyanide gas is lighter than air. That means it disperses and floats up into the atmosphere in any open space, leaving normal air to breathe at lower levels, de Bretton-Gordon said. [The 10 Most Outrageous Military Experiments]

Serious attack

Poisoned letters are nothing new. The substance mailed to the White House was probably a powdered form of the poison, de Bretton-Gordon speculated.

"It's probably something like sodium cyanide: a white substance, not dissimilar to an eggshell if you ground it up," de Bretton-Gordon said. "It is very toxic; you don't need very much of it to kill people" — that is, if it is ingested or gets into a deep cut that carries the poison to the bloodstream.

The White House is used to poisonous packages coming its way. After the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, letters laced with the bacterium that causes anthrax, a serious and often deadly disease, were sent to the White House and several politicians. Ultimately, five people died, and 17 were sickened. In 2013, letters containing the powdery poison ricin were sent to Obama. As a result, the White House likely has strict screening protocols in place for suspicious packages, and the handlers undoubtedly wear gloves, de Bretton-Gordon said.

There are also cyanide-antidote kits, most of which need to be administered quickly, de Bretton-Gordon said. In 2013, researchers developed an antidote to cyanide that could be administered with a jab, similar to the EpiPens used to halt severe allergic reactions. It is very likely that people dealing with the White House have such kits readily available, he added.

Either way, White House officials would already know if someone had been sickened, as cyanide acts very quickly in the body, de Bretton-Gordon said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitterand Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.