This article was originally published on The Conversation. The publication contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Glowing fungi with an on-off system synchronised to their daily rhythms? It sounds implausible but it’s true.

Some mushrooms evolved the ability to glow in the dark in order to attract insects to spread their spores, according to new research in the journal Current Biology.

Fungi are peculiar beings at the best of times. Once believed to be closely related to plants, they are now understood to be more closely related to animals.

Mushrooms, or fungal fruit bodies – the bit you see above ground – may be familiar to us all as food but in the real world mushroom-forming fungi only produce these fruit bodies under special conditions. The main body of the fungus exists largely out of sight as a colony of white thread-like hyphae growing through a food source such as a piece of wood or leaf litter.

In some instances fungal colonies can be old and very large. A colony of Armillaria solidipes in the US is estimated to cover 9.6km2 and be thousands of years old.

Fruit bodies and sexual progeny

Fruit bodies are produced to disperse their sexual progeny as spores. Many fungi shoot spores into the air from the underside of the mushrooms, relying on moving air currents to passively distribute the spores over a wide area.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

If the fungus is several metres up the trunk of a tree, this method is ideal. But wind speed is often either minimal or non-existent on the underside of logs or at the ground level in a dense forest or even underground, where truffles are produced.

So if air movement isn’t effective how can spores be dispersed far and wide? One option is through aroma. Truffles, the fruiting body of the Ascomycete fungi, use their smell to attract fungivores such as pigs or squirrels who eat them and leave spores behind in their waste. Stinkhorn mushrooms have a foul-smelling slime which attracts flies and other insects. The flies eat the slime and unwittingly spread the spores elsewhere.

Luminosity

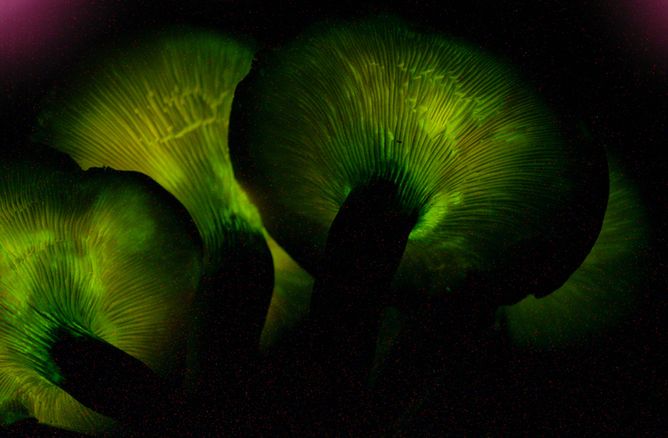

Light is also attractive to many insects. Indeed a number of fungi bioluminesce, emitting a pale green light. One of the first mycology texts I read as a teenager devoted a whole chapter to “luminosity”, mentioning various fungi including some honey fungi (Armillaria), Jack O’lantern (Omphalotus olearius, pictured at the top of this article) and a number of Mycena.

In the new study, a team of Brazilian and American researchers looked at the pale green light emission from fungi, to assess whether it attracted insects and whether brighter light conferred a selective advantage for spore dispersal.

The researchers looked at Neonothopanus gardneri, a particularly intense emitter found at the base of coconut palms in Brazil. It was previously thought their light was emitted continuously as a byproduct of some other round-the-clock metabolic process.

However, the study found the fungus glows only at night, and so is energy efficient; during daytime the light emission would be too faint to be visible. In any case, the best conditions for spore germination in canopy forests are found at night, when it is more humid. If the mushrooms glow only at night then the bioluminescence must serve some purpose.

Camera observations showed the glowing fruit bodies became infested by rove beetles. But these beetles may have been attracted by something else – smell, perhaps.

To specifically test the glowing effect, experimental “mushrooms” made from clear acrylic resin were built. They were equipped with a light emitting diode which operated at a similar wavelength to the mushrooms. To the beetles, the light would have looked the same.

The glowing plastic mushrooms attracted these and various other insects sensitive to green light, while fewer were attracted to non-illuminated controls. From this we can conclude that for these fungi there is a selective advantage to glowing in the dark.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.