6 Crazy Skills That Prove Geckos Are Amazing

Geckos can hang by their toe hairs, scamper up walls and regrow their tails. They've even gone to space. Geckos are amazing creatures with a toolbox full of tricks that science is continuing to uncover.

Here's a look at six of their super skills and the science behind them.

1. Dewdrop cleaning

How do dirty geckos take a bath? According to a new study, they lather up with dewdrops.

Geckos are covered with hundreds of thousands of tiny, hairlike spines that trap pockets of air to help repel water, according to the study, published in the April issue of the Journal of The Royal Society Interface.

When the scientists looked at gecko skin samples under a scanning electron microscope, they saw that these air pockets caused tiny water droplets to bounce like popcorn off of the lizard's skin. [Album: Bizarre Frogs, Lizards and Salamanders]

"If you have seen how drops of water roll off a car after it is waxed, or off a couch that's had protective spray used on it, you've seen the process happening," Lin Schwarzkopf, a professor of vertebrate ecology at James Cook University in Australia and one of the researchers on the study, said in a statement. "The wax and spray make the surface very bumpy at micro and nano levels, and the water droplets remain as little balls, which roll easily and come off with gravity or even a slight wind."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Earlier studies had shown that rolling droplets can clean the hydrophobic surfaces of leaves and insects, but this is the first time the phenomenon has been observed in a vertebrate, the researchers said. Each drop of water can help clear away dust and other small contaminants from the gecko, they found.

"They tend to live in dry environments where they can't depend on it raining, and this process keeps them clean," Schwarzkopf said in the statement.

2. Toe-hair acrobatics

Geckos can scuttle up vertical surfaces and hang from ceilings because they can quickly switch the stickiness of their feet on and off, according to a study published in August 2014 in the Journal of Applied Physics.

Geckos have bulbous toes that are covered with hundreds of microscopic hairs known as setae, the researchers said. (The setae are different from the spines on their bodies that repel water.) Scientists had known that these lizards can get "sticky feet" when these hairs get close enough to a surface that van der Waals forces kick in. (Van der Waals forces are the combination of attractive and repulsive forces between molecules or between parts of one molecule.)

"A gecko, by definition, is not sticky — he has to do something to make himself sticky," study lead author P. Alex Greaney, a professor of engineering at Oregon State University, told Live Science in August. "It's this incredible synergy of the flexibility, angle and extensibility of the hairs that makes it possible."

The researchers made a mathematical model that explains how the setae work. The tiny hairs stick out at slanting angles, they found. If the hairs bend at an angle closer to horizontal, the surface area of the gecko's feet increases, providing a larger area to stick to surfaces and support their weight.

Setae are also flexible and allow a gecko to jump and change direction in a split second. If needed, setae can absorb energy and redirect it, allowing the gecko an expedient escape, according to the study.

3. The tail of the falling gecko

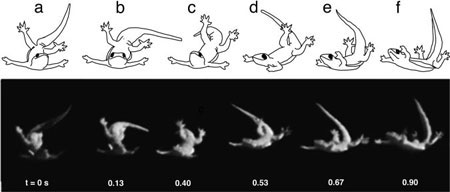

Even with their amazing toe hairs, geckos sometimes take a spill. But a turn of their tail can help them land on their feet, according to a study from 2008.

Using a high-speed camera, researchers examined how geckos responded while walking on slippery vertical surfaces. On a nonslippery surface, the geckos held their tails in the air. But when they encountered a slippery patch, their tail leaned on the wall, "like an emergency fifth leg," the researchers told Live Science in 2008. [Video – Geckos' Talented Tails]

In a separate experiment, the geckos lost their toeholds on a platform. When each gecko fell, it turned its tail at a right angle to its body. Then, it rotated the tail to make the body rotate, the researchers found. When the gecko was right side up, it stopped rotating — a feat that took only about 100 milliseconds, the researchers found in the study, published in the journal the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

4. Goodbye, tail

It's widely known that a gecko can regrow a lost tail. But it wasn't always clear why they lost their tails so easily. Now, researchers know that geckos have preformed "score lines" that help the tails detach if a predator grabs them from behind, according to a study from 2012.

Using high-powered microscopes, the researchers looked at the geckos' tails, and were surprised to find zigzag lines where the tail met the body. They also saw strange, mushroom-shaped structures that might supply the sticky forces needed to keep the tail attached until it's time to be ripped off, the researchers found.

The 2012 study was published in the journal PLOS ONE.

5. Acrobatic tail

Once the gecko loses its tail, the tail doesn't just lie there. It can flip, jump, swing and lunge for up to 30 minutes following separation, according to a 2010 study in the journal Biology Letters.

The researchers studied how the tail pulls off these acrobatics. The signals responsible for the movements are in a piece of spinal cord at the end of the tail, they found. When the tail is still attached to the body, nerve signals from the gecko's brain likely override this control center, the researchers said.

6. Sticky feet

Geckos' feet are supersticky when the air is humid, researchers discovered in 2010.

Humidity can make geckos' setae softer and more deformable, the researchers found. Hence, muggy weather allows the geckos to "glue" themselves to surfaces better than they can in drier weather, according to the 2010 study, published in The Journal of Experimental Biology.

Several experiments showed that high humidity allowed the geckos to make a strong connection between the setae and the surface, and it also allowed the lizards to peel their feet away with ease.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.