Shocking Discovery: Egypt's 'Mona Lisa' May Be a Fake

An ancient Egyptian masterpiece, hailed by some scholars as the "Mona Lisa" of Egyptian painting, is in fact a fake created in the 19th century, a researcher says. But the painting may conceal an authentic Pyramid Age piece underneath.

The "Meidum Geese," as modern-day Egyptologists and art historians call it, was supposedly found in 1871 in a tomb located near the Meidum Pyramid, which was built by the pharaoh Snefru (reign 2610-2590 B.C). The tomb belonged to the pharaoh's son, Nefermaat, and the painting itself was supposedly found in a chapel dedicated to Nefermaat's wife Atet (also spelled Itet). A man named Luigi Vassalli discovered and removed the painting, which is now located in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. [Faux Real: See Photos of Amazing Art Forgeries]

"Some scholars compared it, with due respect, to 'The Gioconda' (Mona Lisa) for the Egyptian art," wrote Francesco Tiradritti, a professor at the Kore University of Enna anddirector of the Italian archaeological mission to Egypt, in a summary of his finds sent to Live Science. The painting's beauty and detail has helped it gain this level of fame.

"Doubting the authenticity of a masterpiece seems almost impossible and it is a mentally painful process," he wrote. "After months of study, I came to the conclusion that there are few doubts on the falsification of the 'Meidum Geese.'"

But while Tiradritti's research suggests the painting is a fake, a real one may be hidden underneath. "The only thing that, in my opinion, still remains to ascertain is what was (or 'is') painted under them. But that can be only established through a noninvasive analysis," Tiradritti wrote.

Tiradritti is set to publish his findings on April 5 in the art specialty papers Giornale dell'Arte and The Art Newspaper, in Italian and English, respectively.He sent Live Science an advance summary of his finds. Tiradritti examined the painting in-person and used high-resolution photographs in his study.

Goosey finds

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The first clues that led Tiradritti to doubt the authenticity of the painting came from studying the birds depicted on it. Two of these birds were unlikely to have flown to Egypt.

Painted on plaster, "the painting depicts three different couple[s] of geese, three turned to the left and three to the right," Tiradritti wrote. Two of the geese were labeled as white-fronted geese (Anser albifrons), with the pair looking to the left identified as bean geese (Anser fabalis) and the pair turned to the right as red-breasted geese (Branta ruficolis), he wrote.

The bean goose breeds in tundra and taiga and winters as far south as the north of Spain, Greece and Turkey, he said, while the red-breasted goose breeds in tundra and rarely winters as far south as the Aegean coast of Greece and Turkey.

That species information in itself doesn't prove the painting is a fake, but it made Tiradritti take a more critical look at it. "After that, it was like to see a castle of cards collapsing."

Hints at forgery

Tiradrittithen found many other problems with the painting. For instance some of the colors are unique and were not used by other ancient Egyptian artists. "Some of the hues (especially beige and marc) are unique in the Egyptian art. Even the shades of more common colors, like orange and red, are not even comparable with the same colors used in other fragments of painting coming from Atet's chapel," he wrote.

The way the geese are drawn, so that they appear to be the same size, is also unusual, Tiradritti pointed out. The ancient Egyptians tended to draw different features of a painting, such as animals and people, in different sizes, sometimes relating their size to their importance.

The artist of the "Meidum Geese" went so far as to have two geese leaning over so that the size of all the geese appears to be balanced. "It is a unique characteristic in Egyptian art, but it is a common feature in modern art," Tiradritti wrote.

Even the cracks on the painting don't seem right, as they "are not compatible with the supposed ripping of the painting from the wall," wrote Tiradritti.

The "Meidum Geese" painting also seems to be painted over another painting, parts of which can still be seen. "The background [of the Meidum Geese] is repainted in a blue hue of grey," he wrote. "The original had a more cream shade and it is still visible on some areas of the painting, especially on the right-top corner and at the two sides [of] the red-breasted goose to the right." [Gallery: Images Reveal Paintings Hidden Beneath Others]

Who did it?

If the painting is a fake, and Tiradritti is convinced it is, then the question is who painted it?

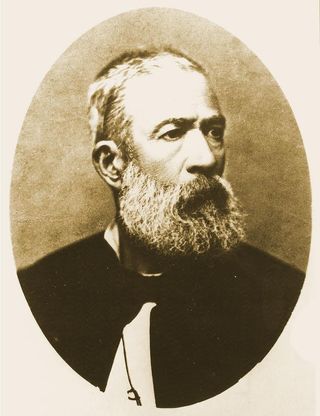

The culprit was likely Vassalli, the person credited with discovering and removing the painting, Tiradritti said. Vassalli was a curator at the Museum Bulaq in Cairo and was an accomplished artist, having studied painting at the Accademia di Brera in Milan, said Tiradritti. [Gotcha! Tales of 8 Famous Art Forgers]

While he is credited with finding and removing the painting, Vassalli never published a word about it, which is unusual given that he loved to talk about his discoveries in Egypt, Tiradritti noted.

"In the manuscripts of Vassalli, there is not [any] mention of the 'Meidum Geese,' and that can be taken as a proof 'ab silentio,' given the fact that he used to mention his exploits even years after he made them. It is highly likely that Vassalli has to be considered the real author of 'the Geese,'" wrote Tiradritti.

A romantic clue

The reason why Vassali forged the painting is a mystery. Tiradritti said the man could have done it because a painting was needed at the Museum Bulaq, or he could have simply done it for fun.

Although Vassali didn't write about the painting, he may have left behind a mark of his work.

While investigating remains from the Atet Chapel, Tiradritti noticed a fragment of painting that Vassalli supposedly found. It was painted with an image of a vulture and a basket. These two signs have meanings in Egypt's hieroglyphic language that spell the initials for Vassalli's second wife Gigliati Angiola.

Tiradritti wrote that the "basket can be read as a 'G,' while the vulture corresponds to an 'A,' giving room to the hypothesis that they have to be interpreted as a monogram."

A big revelation

His finds will be shocking to Egyptologists and art historians, Tiradritti told Live Science in an email. After his work is published, he will be able to get more feedback.

"I already announced it to some of my colleagues, and their first reaction ranged from astonishment to disbelief. At the end, they had to admit that what I am affirming could be likely," he said.

Tiradritti said he hopes that his research will help scholars think more critically about ancient art, especially pieces being sold today on the art market. "I would like to alert my colleagues and invite them to look at the Egyptian art in a different way. We strongly need to revise it."

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.