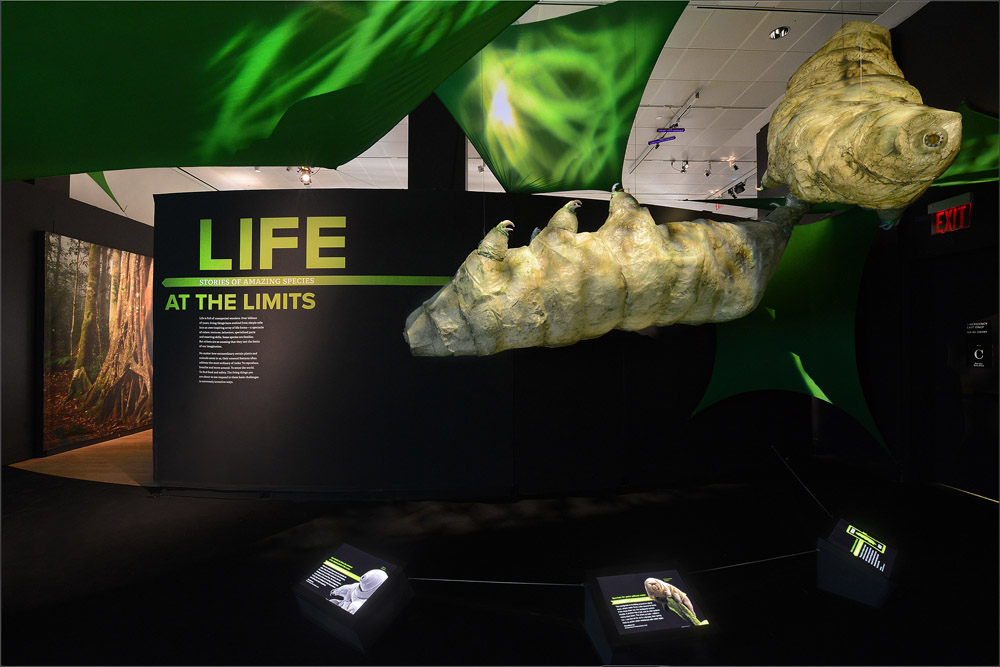

Life at the Limits: Amazing Species Gallery

Animals have some amazing abilities, from a Hercules beetle that can lift 80 times its weight to the microscopic water bear (or tardigrade) that can survive for 10 years without water. These super creatures are being showcased in an exhibit, "'Life At The Limits: Stories of Amazing Species," at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Check out some of the highlights.

Black swallower

The black swallower (Chiasmodon niger) lives thousands of feet beneath the ocean’s surface, where a good meal can be hard to find. Not one to pass up an opportunity, this fish can gulp down prey 10 times its own weight thanks to jaws that can open wide and a greatly expandable stomach. (Credit: © AMNH/R. Mickens.)

Cave spider

The cave spider (Trogloraptor marchingtoni), first discovered in the dark zone of a cave in the coastal forests of Oregon, differs from other spiders so much that scientists created a new family to classify it. One feature that sets it apart: unmatched toothed claws at the end of each leg that are likely used for capturing prey. (Credit: © AMNH/R. Mickens.)

Cecropia moth

The Cecropia moth (Hyalophora cecropia) is a saturniid, characterized by large antennae and a spectacular sense of smell. The branching antennae carry tens of thousands of hairlike structures called sensilla. Some sensilla can detect just one kind of molecule: those produced by females of the same species. (Credit: © AMNH/R. Mickens.)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Hercules beetle

The Hercules beetle (Dynastes hercules) is the largest of the subfamily of rhinoceros beetles. Males use their specialized appendages to fight other males while courting females. These buff beetles can lift up to 80 times their own weight. (Credit: © AMNH/R. Mickens.)

Climbable Hercules beetle

This climbable Hercules beetle (Dynastes hercules) model is 18 times the length and 6,000 times the volume of the actual size of this insect, which is the largest of the rhinoceros beetles. (Credit: © AMNH/D. Finnin.)

Orchid bee

Orchid bees (such as Exaerete frontalis) sip nectar from flowers with their extraordinarily long tongues. Male bees collect fragrant compounds from a variety of plants and store them in pockets in their enlarged hind legs, creating a mixture that is used in their mating ritual. (Credit: © AMNH/R. Mickens.)

Pink salt crystal

This huge pink salt crystal from Searles Lake, California, gets its beautiful color from the microbes within it. Salt levels are so high in Searles Lake that few animals can live there, but the salt-loving microorganisms called Archaea breed in such abundance that they can change the color of the water, as well as of the dried salt crystals. (Credit: © AMNH/R. Mickens.)

The North American porcupine

The North American porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum) is famed for its barbed quills, an effective defense against predators. A porcupine can have as many as 30,000 of these quills, each one tipped with hundreds of tiny hooks that make it hard to remove from punctured skin. (Credit: © AMNH/R. Mickens.)

Porcupinefish

The spot-fin porcupinefish (Diodon hystrix) has spines similar to a porcupine’s. It can also puff up its body by swallowing water, making itself even less appetizing to potential predators. (Credit: © AMNH/R. Mickens.)

Corpse flower

Hailing from the rainforests of Southeast Asia, Rafflesia arnoldii belongs to a group of parasitic plants called corpse flowers. This parasitic plant has no stem, leaves, or roots and is barely visible when not in bloom. When it opens, though, it’s hard to miss: it has the largest flower on the planet and emits a powerful odor of rotting meat to attract its pollinator of choice, carrion flies. Instead of using energy from the Sun to make nutrients, it draws all of its nourishment from a host vine. (Credit: © AMNH/R. Mickens.)

Electrosensing saw

The sawfish (Pristis pristis) hunts with its long, flat snout, which is rimmed with sharp points that give it its signature look. This blade serves as both a weapon and a scanning device—its surface is speckled with sensitive pores that detect the weak electric fields produced by its prey. (Credit: © AMNH/R. Mickens.)

Tardigrade

This 10-foot model of the microscopic tardigrade, an animal that enters a low-metabolic state to endure stressful environmental conditions, is 6,000 times life size (by length). (Credit: © AMNH/R. Mickens.)

Tardigrade

More than 1,000 species of tardigrades are found across the world in habitats that range from bubbling hot springs to holes in the Antarctic ice, and from the Himalayas to the deep ocean. When environmental conditions get too tough, these microscopic animals can enter a low-metabolic state called cryptobiosis, during which they are just about invincible. (Credit: © Eye of Science/Science Source.)

Waterfall climbing cave fish

Like many cave-dwelling animals, waterfall climbing cavefish (Cryptotora thamicola) lack eyes and skin pigment. Members of this species, which is found in only two caves in Thailand, also have enlarged fins that they use to hold onto or climb up rocks in fast-moving streams. (Credit: © AMNH/D. Finnin.)

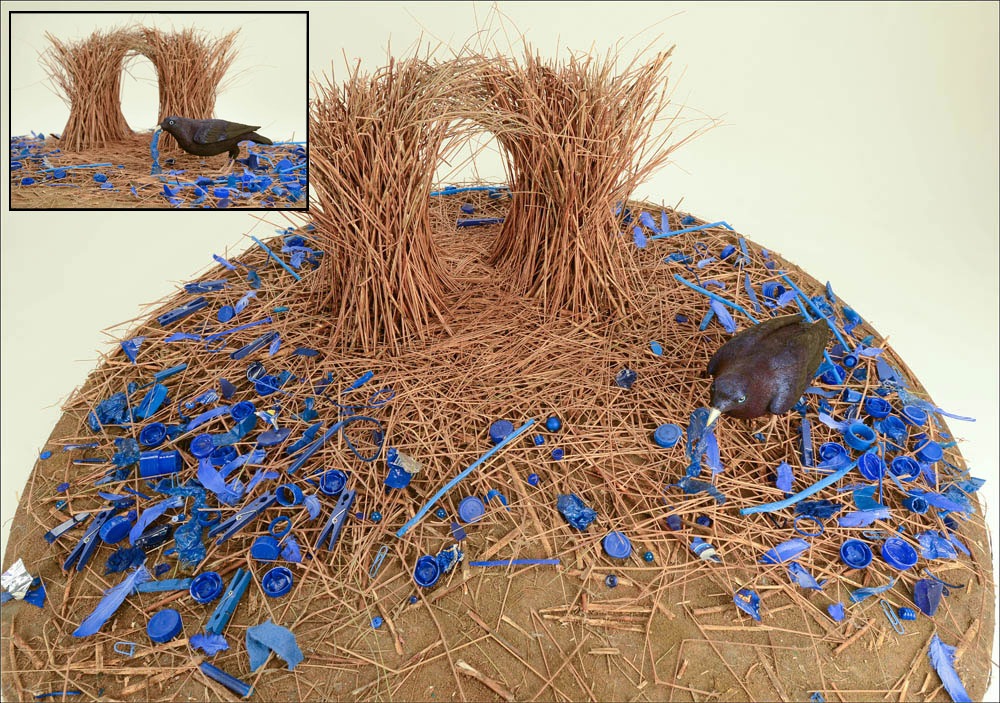

Bowerbird

When the male satin bowerbird (Ptilonorhynchus violaceus) is ready to mate, it builds an elaborate nest-like structure called a bower, which it decorates with flowers, shells, feathers, and other eye-catching baubles to attract females. (Credit: © AMNH/R. Mickens.)

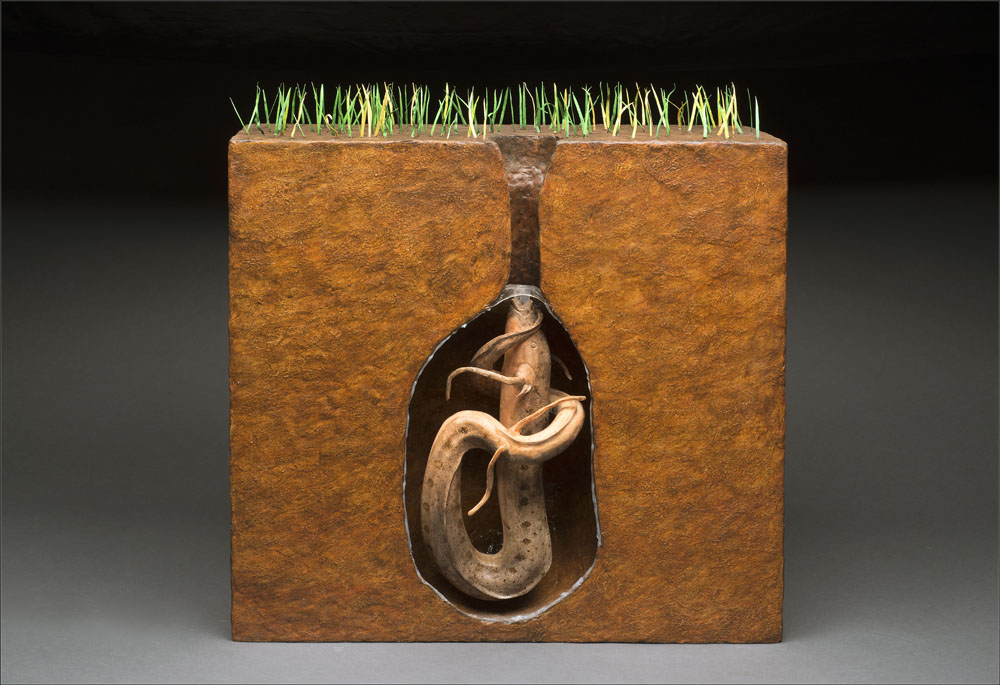

African lungfish

African lungfish (Protopterus dolloi) can survive for months to years without food or water in a special burrow. They live in shallow pools, rising to the surface every five minutes or so to breathe atmospheric air. If its pool dries up, the lungfish tunnels headfirst into the mud and secretes a mucus cocoon, leaving an opening through which it breathes air. (Credit: © AMNH/R. Mickens.)

Elephant seal

This life-size model (20 feet) is of the southern elephant seal (Mirounga leonina), which spends two months a year living on land in Antarctica and the rest of the year hunting for fish and squid in the frigid Southern Ocean. While hunting, the elephant seal can dive down nearly a mile and may not resurface to breathe for up to two hours. (Credit: © AMNH/D. Finnin.)

Dragonfly

Dragonflies are among the world’s fastest insects, achieving speeds up to 30 miles per hour. They’re also formidable predators: with amazing vision and maneuvering capabilities—they can fly backwards and upside down and hover for a minute at a time—they have a midair capture rate of 95 percent. This model of a wandering glider dragonfly (Pantala flavescens) is 47 times life size (by length). (Credit: © AMNH/R. Mickens.)

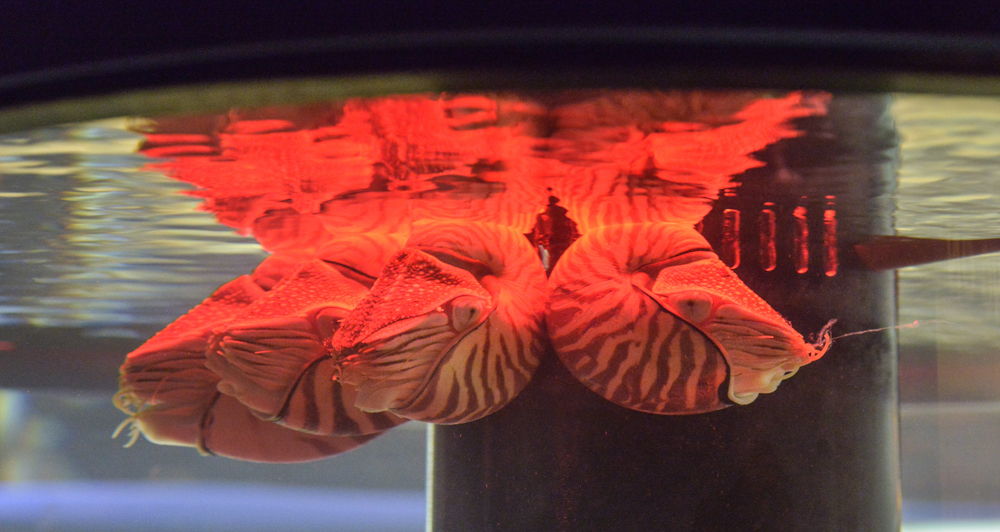

Nautilus

The slow-moving nautilus (Nautilus pompilius), shown live in one of the exhibition’s aquariums, moves using jet propulsion: it shoots water out of its funnel (siphon), which propels it in the opposite direction of the flow. A pair of strong muscles inside the shell forces the water through. (Credit: © AMNH/D. Finnin.)

Axolotl

This unusual salamander (Ambystoma mexicanus) lives its whole life underwater and retains many of its juvenile traits, such as its external gills and lidless eyes. It also has the ability to regrow limbs repeatedly and can even regenerate a crushed spinal cord. (Credit: © AMNH/D. Finnin.)

Coral reef

Corals (model of a section of the Great Barrier Reef, Australia) are animals that begin life floating in the water but settle and live anchored to the sea floor. Adult corals can’t move in search of mates and instead spawn in unison, releasing billions of eggs and sperm. Corals can also produce clones of itself. (Credit: © AMNH/R. Mickens.)

Tube worm

Red, feathery tips of giant tube worms (Riftia pachyptila) poke out of long, white tubes, as seen in this model. These worms have no mouths and cannot eat. Instead they absorb chemicals from the surrounding water that microbes living inside their bodies convert to nutrients. (Credit: © AMNH/R. Mickens.)

Titan flower

The flowering titan arum (Amorphophallus titanium) in Indonesia rarely blooms, but when it does, the sight—and smell—can be utterly breathtaking. At night, the tropical giant unfurls and releases a seductive scent to lure pollen-spreading insects. Its strong perfume resembles the stench of rotting flesh, attracting sweat bees as well as flies and carrion beetles—insects that typically dine on decaying animal remains. (Credit: © AMNH/D. Finnin.)

Mimic octopus (illustration)

The mimic octopus (Thaumoctopus mimicus) can imitate a number of poisonous and venomous creatures, including a flatfish, a lionfish, and a sea snake, to scare off predators. To mimic these animals, this octopus’s skin creates colors and patterns like a video screen, and its boneless body takes on a variety of shapes. This species is so difficult to spot that it was unknown until 1998. It even has its own mimic, the harlequin jawfish (Stalix histrio). (Credit: © AMNH/5W Infographics/P. Velasco.)

Species interactive

Visitors can test the ‘super powers’ of several species that they encountered in the exhibition. Through exploration of several virtual environments and the use of guided gestures using whole-body, motion-sensing Microsoft Kinect technology, visitors will cause creatures to behave in ways consistent with some of their amazing abilities, highlighting why these creatures live life at the limits. (Credit: © AMNH/R. Mickens.)

Paper wasp nest

Every inch of this impressive nest was made from chewed-up plant matter, carried inside the mouth of a wasp and mixed with saliva to make the paper-like walls. Inside the nest, which promotes the safety in numbers defense for wasps, are six-sided cells that look like honeycomb. Some paper wasp nests can have 130,000 individual cells. (Credit: © AMNH/D. Finnin.)

Talons of the harpy eagle

These touchable talons belong to the one of the world’s largest birds of prey: the harpy eagle (Harpia harpyja). A harpy eagle’s grip is strong enough to catch and subdue prey close to its own body-weight, or up to 20 pounds (9 kilograms). (Credit: © AMNH/R. Mickens.)

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+.