Huge Colorado Floods Helped Sculpt Mountains

In 2013, heavy rains unleashed devastating slurries of rock, soil and water on cities and towns along the Colorado Rockies. A new study has shown that although these huge floods are rare in human lifetimes, they are responsible for sculpting the steep mountains in this semiarid landscape.

"While it strikes us as very random, our research suggests this is one of the formative processes in this landscape," said lead study author Scott Anderson, a geomorphologist with the U.S. Geological Survey in Tacoma, Washington.

The 2013 Colorado floods triggered more than 1,100 landslides and debris flows in the Front Range after several days of unusually heavy rain in September. The resulting debris flows carried huge volumes of rock and sediment down mountain valleys, scouring out river channels like sandpaper. [See photos of Colorado's Landslides]

"The erosion that occurred during this one event represents the removal of hundreds to a thousand years of accumulated debris," Anderson said.

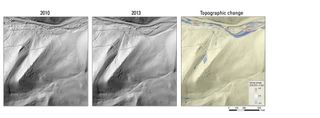

Anderson was a research scientist at the University of Colorado, Boulder, when the storms hit, and was part of the massive scientific response to the destruction. His role was to compare high-resolution surface maps that were taken before and after the floods with lidar, a measurement technique that uses pulses of laser light to map surfaces and structures. By comparing the lidar maps, Anderson and his colleagues could detect where sediment was removed and where the floods deposited debris.

The team identified 120 landslides in the area covered by the lidar maps, which transported more than 4 million cubic feet (114,000 cubic meters) of debris. The findings were published March 27 in the journal Geology.

Within the debris flow channels, the floods removed up to 3 feet (1 meter) of rock and sediment, Anderson said. The total amount of erosion, averaged over the entire landscape measured in the study, is 0.6 inches (1.5 centimeters). While that's shorter than a fingernail, the erosion compares in scale to the amount of lowering that takes place over millennia along the Front Range, Anderson said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

According to techniques that measure the length of time that rocks have been exposed at the surface, the rocks weather away at 0.8 inches to 2.4 inches (2 to 6 cm) per 1,000 years. The results suggest that, like an old house having its paint sandblasted away, hundreds of years of built-up sediment shot out of the canyons in a geologic instant during the 2013 floods.

If such a huge amount of material had moved miles in a wet landscape such as Washington or Oregon, it wouldn't be considered shocking, Anderson said. "The presence of so many debris flows in this semiarid landscape is pretty novel," he told Live Science.

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.