'Extinct' No Longer? Brontosaurus May Make a Comeback

The Brontosaurus is back. Or at least it should be, according to a new analysis of the long-necked dinosaur family tree.

The study researchers suggest the dinosaur currently known as Apatosaurus excelsus is different enough from its Apatosaurian kin as to be a different dinosaur altogether. Because A. excelsus was famously first known as Brontosaurus until 1903, the species would revert back to that original name and become Brontosaurus once again.

It's a proposal that excites some paleontologists and leaves others skeptical, but researchers say it's entirely possible that Brontosaurus may eventually regain its place in the scientific nomenclature. [See Images of an Apatosaurus Discovery]

"The big picture is, there are independent groups of researchers looking at these dinos and these relationships, and they are independently arriving at the same conclusion, that the diversity of this family of dinosaurs is greater than previously recognized," said Matthew Mossbrucker, the director and curator of the Morrison Natural History Museum in Colorado. Mossbrucker was not involved in the new study, but is "wholly in favor of bringing the genus Brontosaurus back," he said.

Brontosaurus background

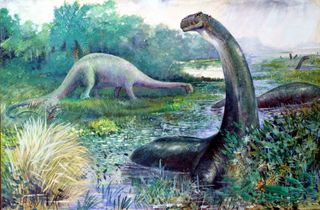

The saga of Brontosaurus is as long as this sauropod's snakelike neck. In 1877, the geologist Arthur Lakes sent paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh some fossilized bones, which Marsh described as a new late-Jurassic sauropod, Apatosaurus ajax. In 1879, Marsh's team found another long-necked dino in the same era rock, which Marsh concluded was a different genus and species altogether — Brontosaurus excelsus.

The Brontosaurus name was not long-lasting, however. In 1903, the paleontologist Elmer Riggs determined that A. ajax and B. excelsus were more closely related than Marsh had believed. Apatosaurus, being the first named, took precedence, and Brontosaurus was no more. Instead, the dinosaur species once known as B. excelsus became A. excelsus. The Brontosaurus moniker persisted in popular culture, but not among scientists.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Not among most scientists, anyway. There have been occasional calls to re-examine the species. Paleontologist Bob Bakker, the curator of paleontology at the Houston Museum of Natural Science, has argued for a revision of the A. excelsus name since the 1990s.

"These guys should never have been lumped [together] back in 1903 or '04," Bakker told Live Science. He cites differences in the A. excelsus shoulder blade, head and neck that separate it from other Apatosaurs. But the only systematic analysis of Apatosaurus traits, published in the National Science Museum Monographs in 2004, upheld the current naming conventions.

Revising the family tree

The new research examines not only Apatosaurs, but all long-necks in the Diplodocidae family, the group that includes Apatosaurs and Diplodocuses. The researchers examined 477 different morphological traits from individual specimens found in museums in Europe and the United States. The study started simply, said lead researcher Emanuel Tschopp, a paleontologist at the Universidade Nova de Lisboa in Portugal. [6 Strange Species Discovered in Museums]

"The idea was to identify some new skeletons that there are in a museum in Switzerland down to the species," Tschopp told Live Science. "At some point, we figured out that in order to do this, we also had to revise the species taxonomy of the group because it was not known in enough detail to really see where our new specimens would belong."

Tschopp and his colleagues cataloged the differences in various bony features of Diplodocidae dinosaurs and used a statistical method to quantify how different each dino was from the others. From there, they separated the specimens into individual species and genera, or closely related groups of species.

The most provocative result was how much A. excelsus stood out.

"We found that the differences between the genus Brontosaurus and the genus Apatosaurus are so numerous that they should be kept apart as two different genera," Tschopp said.

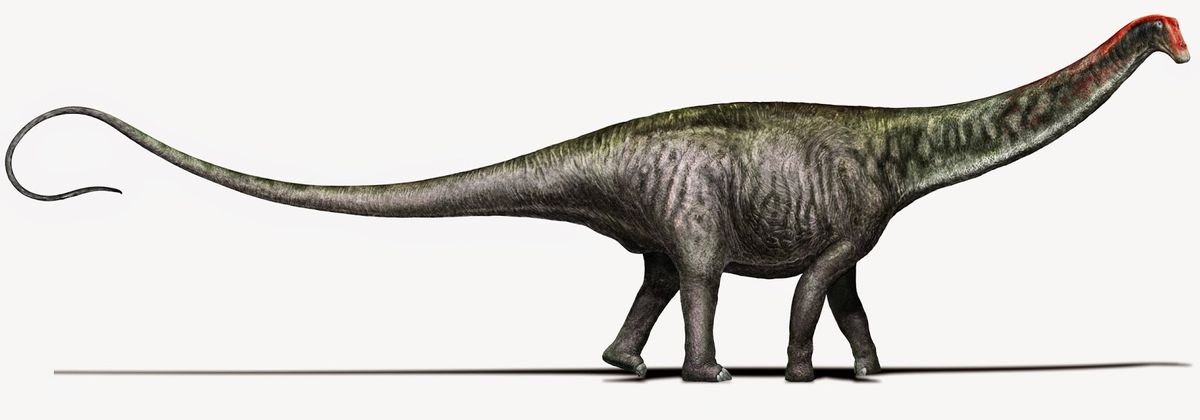

Most notably, he said, Apatosaurus would have had a wider, more robust neck than Brontosaurus. The findings appear today (April 7) in the open-access journal PeerJ.

Dino debate

Tschopp's work did not take into account Apatosaurus excelsus' skull, because paleontologists disagree about whether a true skull of this animal has ever been found. Bakker and Mossbrucker argue there is good evidence that true skulls have been found; other paleontologists are skeptical of the field drawings and diagrams of Arthur Lakes, who found the original Apatosaurus specimens in the late 1800s.

If Bakker and Mossbrucker are right, the skulls of A. excelsus and other Apatosaurians bolster the Brontosaurus claim. The nasal chambers in A. excelsus' probable skull fossils are larger than in other species, Bakker said, which would have made its bellows higher-pitched. Its muzzle, shoulders and neck joints are different, which would have altered its maneuverability and posture, Bakker added. All of these changes mattered ecologically.

"It's important to recognize the distinctions, because this group of critters, the long-neck Apatosaurs, evolved faster than we've been giving them credit for, and they evolved in sectors of anatomy that are really interesting," Bakker said. "Why would they change their head-neck posture? Why? I suspect part of it might be social behavior, the way they signaled to each other with head flips and chin bobs."

But discerning behavior and evolution from bone shapes and features is a tricky business.

"The question for me is when we look at these changes, and we say the shape of this bone is different, the shape of that bone is different, it's hard for me to say that they are equivalent changes," said John Whitlock, a paleontologist at Mount Aloysius College, who was not involved in the study but who reviewed it for publication. For example, one change could require the alteration of 400 nucleotides of DNA, Whitlock told Live Science, and another just a couple of nucleotides.

"Evolutionarily speaking, those are not necessarily equivalent," he said.

If anything is certain, it's that bringing back Brontosaurus will require a lot more debate (and, ultimately, a ruling by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature).

"For sure, there will be other researchers that are maybe not convinced or have their own evidence against the separation of the two," Tschopp said. "In the end, this is how science works."

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.