Why You Get the Joke: Brain's Sarcasm Center Found

Sarcasm might feel like a natural way to communicate to many people, but it's sometimes lost on stroke survivors. Now, a new study finds that damage to a key structure in the brain may explain why these patients can't perceive sarcasm.

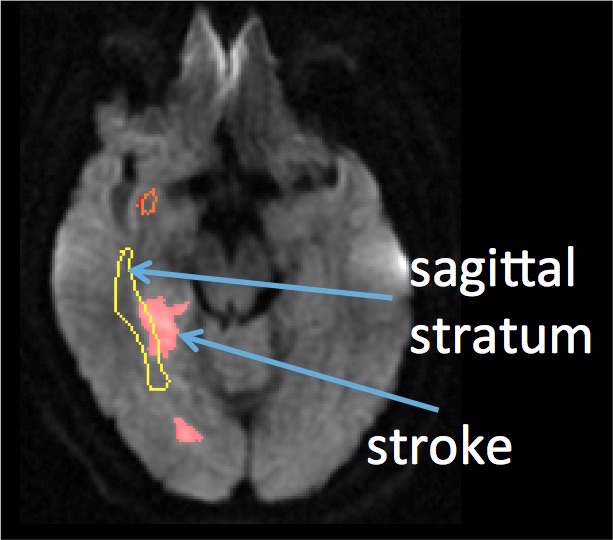

Researchers looked at 24 people who had experienced a stroke in the right hemispheres of their brains. Those with damage to the right sagittal stratum tended to have trouble recognizing sarcasm, the researchers found. This bundle of neural fibers connects a number of brain regions, including those that process auditory and visual information.

The finding may help families caring for stroke survivors understand why their loved ones don't understand the reason for an eye roll or a certain tone of voice, according to the study, published March 25 in the journal Neurocase.

"We typically tell families that they [right-hemisphere stroke survivors] might have difficulty understanding sarcasm, so it's better just to be literal," said the study's senior researcher, Dr. Argye Hillis, a professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore. "If you want to say something, say it straightforwardly." [Top 10 Mysteries of the Mind]

Hillis has spent a large part of her career working with people who have lived through a right-hemisphere stroke. These people have no problems in hearing and understanding words, but often misunderstand the meanings of sarcastic quips, because they struggle to recognize a speaker's facial expressions, emotions and intent, she said.

"Even though they understand the words, there's often a real failure of communication," Hillis told Live Science.

It's no wonder sarcasm can be hard to interpret; it's a complex way to communicate, Hillis said. First, the person has to understand the literal meaning of what someone says, and then the listener has to detect the components of sarcasm: a wider range of pitch, greater emphatic stress, briefer pauses, lengthened syllables and intensified loudness relative to sincere speech, the researchers wrote in the study.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"There're a number of cues people use, and it's both facial cues and tone of voice," Hillis said.

Brain scans

Earlier studies have linked damage to certain areas of the cortex (the brain's surface) to difficulties in understanding sarcasm, the researchers said. But it was less clear whether the brain's white matter tracts, which relay information between brain regions, also played a role.

To investigate, the researchers took MRI brain scans of the 24 stroke patients, and looked for damage in eight white matter tracts in each patient. The participants also took a sarcasm test, in which they listened to 40 sentences spoken either sincerely or sarcastically, and had to identify which was which. (For example, one sentence was, "This looks like a safe boat.")

After the researchers controlled for age and education level, they found that damage to the right sagittal stratum significantly impaired a person's ability to understand sarcasm.

Five of the participants had significant damage to this structure, Hillis said. On the sarcasm test, these participants correctly identified only about 22 percent of the sarcastic statements, compared with 50 percent of patients who did not have damage to that structure.

The right sagittal stratum group also did worse in identifying sincere statements: They got 57 percent correct compared with 67 percent from the group without sagittal stratum damage.

On average, people in the general population identify 90 percent of sarcastic statements correctly, Hillis said.

It makes sense that people with sagittal stratum damage would have trouble deciphering sarcasm, she said. The tract connects different parts of the brain, such as the frontal cortex (important for decision making) and the thalamus (which processes both auditory and visual information).

Future research may find ways to help people with damage to the right sagittal stratum regain the ability to recognize sarcastic cues. "Alternatively, family and friends can be counseled to avoid sarcasm to prevent misunderstandings," the researchers wrote in the study.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.