Wildfires, water rationing and snow-free mountaintops are all becoming the new norm in California.

The Golden State is experiencing the most severe drought on record, and research suggests the conditions will only worsen in the coming decades.

"Climate change is going to lead to overall much drier conditions toward the end of the 21st century than anything we've seen in probably the last 1,000 years," said Benjamin Cook, a climatologist at the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York City.

But despite the drier conditions and the apocalyptic headlines, California is unlikely to become a parched, uninhabitable hellscape, experts say. Southern California's forest may transform into scrub and grassland. And a drier climate may force a transformation or reduction of the state's agricultural economy. But with some forethought and planning, the state should have enough water to support the millions of people who live there, experts say. [6 Unexpected Effects of Climate Change]

"In the next few decades, warming is not going to cause California to be a wasteland," said A. Park Williams, a bioclimatologist at the Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University in New York City.

Drying trend

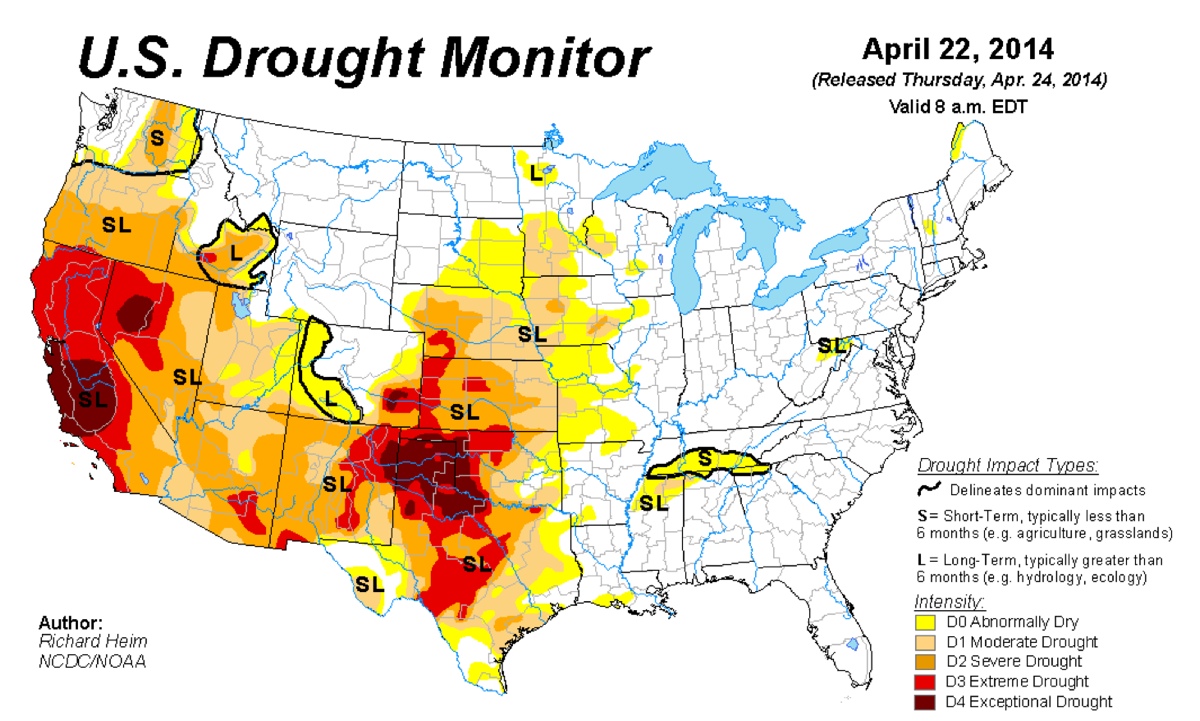

California is facing its worst drought on record, with snowpack in the state's Sierra Nevada at an all-time low. About 98 percent of the state is experiencing moderate to exceptional drought, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The past several years of low rain and snowfall aren't that unusual. But thanks to greenhouse gas emissions, California is warmer, on average, than it has been in the recent past. That hotter weather means the water that falls on the ground evaporates quickly, said Noah Diffenbaugh, a climatologist at Stanford University, in Palo Alto, California.

"We're on the cusp in California of having every year be a warm year, which means that when low precipitation does occur there's going to be a much higher risk that that low precipitation produces drought," Diffenbaugh told Live Science.

In a study published in February in the journal Science Advances, Cook and his colleagues found that the risk of a megadrought this century would rise dramatically if greenhouse gas emissions aren't checked. As a result, though California typically faces droughts that last from one to three years, the state could experience droughts that last several years or even two to four decades, Cook said.

Changing landscape

The dryer, hotter conditions will transform the landscape. The forests in Southern California may give way to shrub and grassland, Williams said.

And that transition won't be gradual. In areas that have experienced similar changes, "these transitions occur largely as catastrophes," Williams told Live Science.

For instance, wildfires or bark beetle infestations will likely take out patches of forest over a matter of weeks or a few seasons, Williams said.

The Sierra Nevada mountain range has a diverse set of plants and animal species, so the proportions of those species may change. Because climate models predict slightly more winter precipitation and relatively constant temperatures, the coastal redwoods of Northern California, which depend on fog, are likely to be OK, Williams said.

Avoiding catastrophe

Still, there is time to ensure enough water is available for the millions who live in the state, all the experts Live Science spoke with said.

"There are a lot of opportunities to deal with these potentially significant droughts in the future, but we just need to be a little bit proactive about it and we need to plan ahead," Cook said.

However, Californians have a short memory when it comes to droughts and don't follow through with actions taken during drought years, he said. For instance, desalination plants were built during droughts, but then partly dismantled when precipitation levels rose, Williams said. [The Worst Droughts In U.S. History]

To address the water shortage, the state must tackle agricultural water use, which comprises about 70 to 80 percent of the state's total water usage. Water-hogging plants such as almonds and lettuce may need to take a back seat to more drought-tolerant crops, Cook said. The state could help subsidize a shift to drip irrigation, which delivers moisture directly to a plant's roots. Long-term, agriculture may become a less prominent part of the economy, Williams said.

Slowing the pace of climate change could decrease how dramatically the state changes, though some climactic change is already baked in, Diffenbaugh said. And steps to improve water storage during wet years, like increasing the use of reservoirs, could also help, Cook said.

To prevent or slow ecosystem change, the state should prioritize controlled burns — where forest managers thin the forest with small fires — so that ecosystem-altering conflagrations like the 2013 Yosemite Rim Fire don't have enough wood on the forest floor to get going, Williams said.

Either way, to avoid catastrophe the system needs to adapt to the coming reality. California has built complex systems for managing water policy and infrastructure, but those systems need to be rethought, Diffenbaugh said.

"Those were all built in an old climate, and the reality is, we're in a new climate," Diffenbaugh said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.