Will China Become the No. 1 Superpower?

As the world focuses on China during the Olympics and keeps a watchful eye on Russia's military moves in Georgia, there is an underlying expectation — and for some, fear — that China is poised to become the world's new No. 1 superpower.

In fact, a good number of people in many countries believe the torch has already been passed.

In Japan, 67 percent of the people think China will supplant the United States as the world's premiere superpower, according to a recent Pew Research Center survey. Fifty-three percent of Chinese see that as their fate.

"Most of those surveyed in Germany, Spain, France, Britain and Australia think China either has already replaced the U.S. or will do so in the future," according to the Pew report released in June.

In the United States, hope reigns: 54 percent of Americans doubt China will win out.

Most experts on the topic range from unsure to very skeptical that China is ready to climb the podium. Yet there are clear signs of serious progress.

According to one projection, China is on the verge of supplanting the United States as the primary driver of the global economy, a leading role that dates back to the end of World War II. The Georgia Tech researchers who make this claim have little doubt that China, owing to all the money it now invests in research and development, will soon become the No. 1 technological superpower. Another study, done last year, points out that the sheer numbers of people in China will propel such a transition by mid-century.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

All of this has many global citizens worried.

"The perception that China fails to consider the interests of others when making foreign policy decisions is widespread, particularly in the U.S., Europe, the Middle East and among China's neighbors South Korea, Japan and Australia," the Pew analysts wrote earlier this month.

But people have been predicting China's ascendancy to world dominance since Napoleon's time. So what does it mean to be the superpower? The answer to that question renders China's fate as murky as the skies over Beijing.

Four elements of a superpower

A superpower "is a country that has the capacity to project dominating power and influence anywhere in the world, and sometimes, in more than one region of the globe at a time," according to Alice Lyman Miller, a research fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University and an associate professor in National Security Affairs at the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School.

Four components of influence mark a superpower, Miller says: military, economic, political, and cultural.

After World War II, the United States was virtually the only country left standing and it accounted for 40 percent of world trade in the post-war years, according to Miller. Most countries pegged their currencies to the dollar. English came to be the dominant language of global politics and business and American culture grew globally pervasive. When the Soviet Union collapsed, the United States became inarguably the top superpower.

One key to this supremacy is hegemony. The word derives from a Greek term for leadership. It is the ability to dictate policies of other nations. It's often accomplished by brute force, as in the days of the Roman and British empires. Germany took a crack at it in the late 1930s. Russia has worked at it but by many historians' accounts never achieved hegemony in any global sense. China is often considered regionally hegemonic.

In addition to sheer military might, the United States achieved hegemony through economic, political and cultural influence — factors that many see as being on the wane now.

A couple years back, the presidential hopeful Ron Paul echoed what many analysts perceive: The "dollar hegemony" — U.S. currency's strength and attractiveness — has been a key factor in U.S. dominance, but "our dollar dominance is coming to an end."

Though it has become a great power in a "spectacular" rise over the past two decades, "China is not now a superpower, nor is it likely to emerge as one soon," Miller wrote in 2004, standing by that argument this week in an email.

Yet superpowers come and go. And one way to bring them down is to stretch them thin.

Adam Segal is the Maurice R. Greenberg Senior Fellow for China Studies at the nonpartisan Council on Foreign Relations. In a telephone interview this week, Segal said you could spin a very pessimistic scenario in which a regional conflict like the one between Russia and Georgia might occur in Asia, involving China. The United States would be faced with "lots of pretty unattractive policy options considering we don't really want to have war with either Russia or China, given the fact that we're fighting two wars already."

Segal stresses, however, that he doesn't see that happening. China's behavior since the mid-1990s "has been pretty moderate," Segal said. The country's mantra has been "harmonious development," an effort to convince neighbors that what's good for China (economic growth) is good for them.

"China's relations with most of its neighbors are pretty good," Segal said.

In fact, many people who study these things see the world possibly entering a new phase where superpowers are not what they used to be. Rather than a unipolar world, where one country calls the bulk of the shots, the future might prove to be multipolar, where three or more nations share the preponderance of influence. Most analysts agree China is taking a seat at the world power table, the question is whether the country is motivated to seek world domination or prefers to play nice.

"The Chinese government does all that it can to avoid clashes with the United States," said Susan L. Shirk, director of the University of California Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation. Shirk is a former Deputy Assistant Secretary of State responsible for U.S. relations with China and author of "China: The Fragile Superpower" (Oxford University Press, 2007).

"It [China] would rather be on the same side of an international issue than at odds with us," Shirk told LiveScience. "Compared to many other countries, including our friends and allies, China has been much less critical of U.S. actions in Iraq."

World views

Meanwhile, a look at several reports from Pew illuminates public sentiments and concerns about China, from within and from the outside.

The results, mostly from surveys done this year, paint a picture of a people growing more satisfied with their country's status and direction and increasingly confident that they will ultimately be the world's top dog.

More than 80 percent of the Chinese people surveyed have a positive view of both their country and their economy. Of 24 countries polled on these points, China was first in both categories.

"Although levels of personal satisfaction are lower, and by global standards Chinese contentment with family, income and jobs is not especially high, these findings represent a dramatic improvement in national contentment from earlier in the decade when the Chinese people were not nearly as positive about the course of their nation and its economy," the Pew analysts state.

A Pew survey released in July found "broad acceptance among the Chinese of their country's transformation from a socialist to a capitalist society." Some 71 percent said they like the pace of modern life and 70 percent said they think people are better off in free markets.

Not everyone is keen on the site of the 2008 summer games, of course, with many activists and politicians citing a human rights record that could use some improvement.

A Pew survey released in June asked people if they thought hosting the Olympics in China was a good idea. The answer was "no" from 43 percent of Americans, 55 percent of Japanese and 47 percent of Germans. But in 14 of 23 countries, "clear majorities favor having the games in Beijing." The largest "yes" percentages came from Nigeria (79 percent), Tanzania (78 percent) and India (76 percent).

The Olympics will help China's image, say 93 percent of the Chinese surveyed.

Co-opting U.S. strategy

The United States has driven the world economy since the end of World War II. But part of the formula relied on for that success — heavy investment in research and technology — is being co-opted by China, just as Japan and other countries have done in recent decades.

Meanwhile, many American scientists complain that morality-based politics and a lack of federal funding has seriously eroded the U.S. leadership in science and technology in recent years.

A study earlier this year by the Georgia Institute of Technology projects China will soon pass the United States in the ability to export technology-based products.

"For the first time in nearly a century, we see leadership in basic research and the economic ability to pursue the benefits of that research – to create and market products based on research – in more than one place on the planet," said Nils Newman, co-author of the study. "Now we have a situation in which technology products are going to be appearing in the marketplace that were not developed or commercialized here. We won't have had any involvement with them and may not even know they are coming."

The study, which relied on both statistics and expert opinions, finds the gains China is making "have been dramatic, and there is no real sense that any kind of leveling off is occurring," Newman said in January.

"China has really changed the world economic landscape in technology," said Alan Porter, another study co-author. "When you take China's low-cost manufacturing and focus on technology, then combine them with the increasing emphasis on research and development, the result ultimately won't leave much room for other countries."

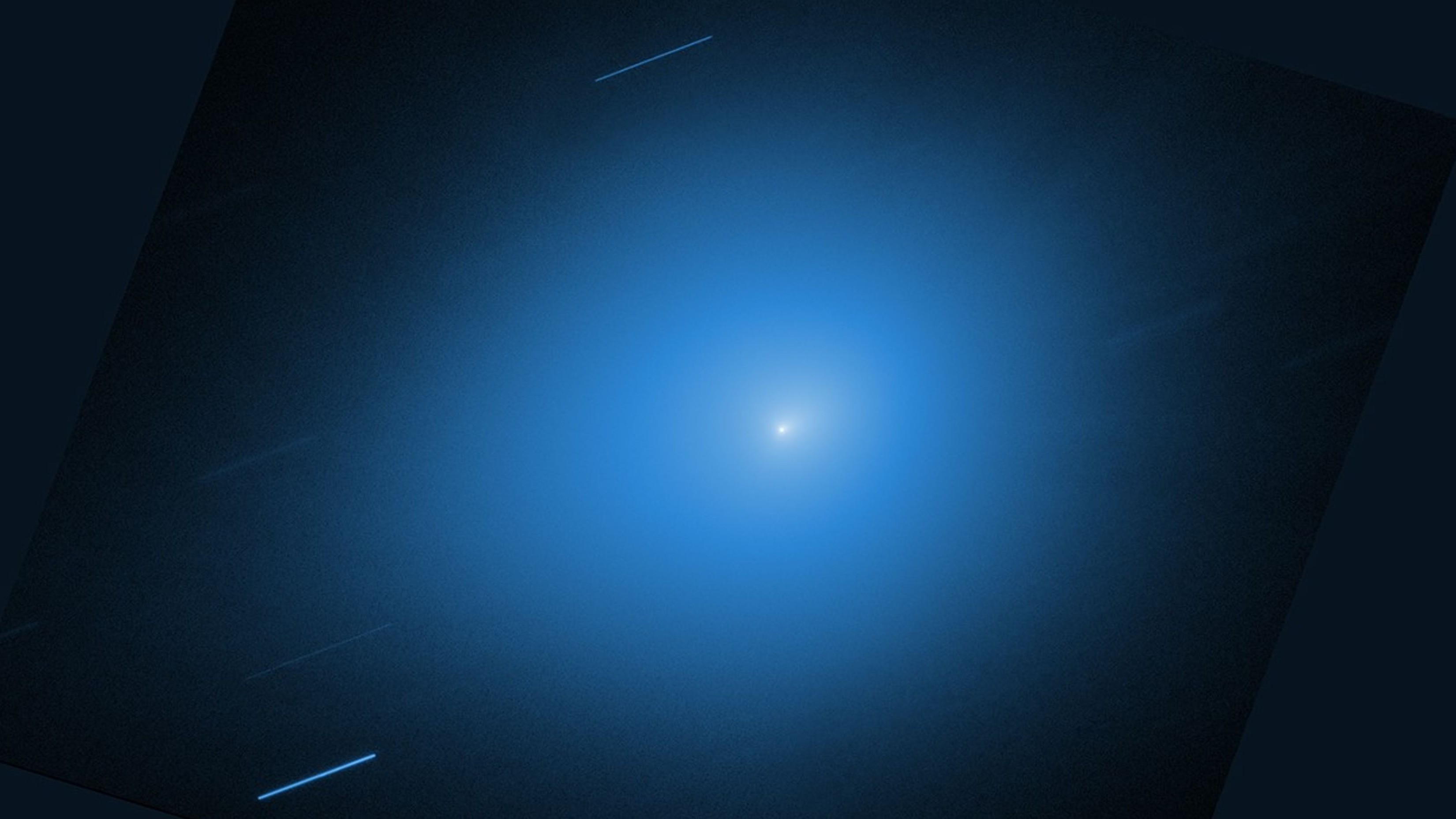

Porter said Chinese scientists now write more scientific papers in international journals than any country for a number of key emerging technologies. China has also entered the exclusive club of nations putting people in space.

"They are also dramatically increasing their R&D," Porter told LiveScience. "When they get better at innovation — taking the results of that R&D and fueling new technology development — they will be the No. 1 technology superpower."

Porter notes that technically based economic competitiveness is not the only measure of a superpower, but he thinks it may be the most important one. He and Newman note that the United States has a mature economy, while China is just getting started.

"It's like being 40 years old and playing basketball against a competitor who's only 12 years old – but is already at your height," Newman said. "You are a little better right now and have more experience, but you're not going to squeeze much more performance out. The future clearly doesn't look good for the United States."

A study last year by Siddharth Swaminathan and Tad Kugler of the La Sierra University School of Business projected that China will dominate the international economy and become the top superpower by mid-century. They note that India will be close on China's heels.

While the U.S. population is 305 million people, China's is 1.3 billion, and India's is 1.1 billion.

"These emerging superpowers, through the sheer size of their respective populations and coupled with increasing access to education and technology, may become contenders for international dominance even before reaching the income per capita levels of the developed nations of today," the researchers write.

Challenges remain

Segal, of the Council on Foreign Relations, is skeptical that the Chinese will emerge as a superpower. He does not think they'll have the economic, military, political or cultural might to go for the gold anytime soon. They have no aircraft carriers and no ability to extend their military reach beyond the Pacific, he points out. And while their economy is growing rapidly, the focus is largely on domestic development, he said.

America's open, democratic society, and the fact that other nations sought to emulate it, was an important factor in the U.S. becoming a superpower, other historians say.

China lacks the sort of transparent political system that Segal sees as necessary to achieving superpower status.

"China's behavior during the SARS epidemic, when it hid what was going on and lied to the international community, suggests that it is not ready for that type of leadership," Segal said. "We saw more openness after the Sichuan earthquakes, but the fundamental system remains the same."

"No other country seeks to emulate China's political model," Miller argues. Culturally, Miller points out that Chinese is unlikely to supplant English as the language of international politics anytime soon.

Some analysts think the Olympics could mark a turning point for China.

The goal of Chinese leadership in hosting the Olympics was to "signal to the rest of the world that China has arrived," said Jeffrey Bader, director of the John L. Thornton China Center at the Brookings Institution.

"China will enter a new era after the Olympics," said Cheng Li, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. The country will become "more open, more transparent and more tolerant. But this will not be achieved overnight. It will take time." If China is to become a major power, the government has to deal with minority issues, such as Tibet, in more sensitive ways than simply cracking down, he said. He does not think the Chinese government nor its people recognize that yet, "but I hope the Olympics serve as a wake-up call."

Economic juggernaut?

By one economic measure, China falls short of global domination for now. The country's gross domestic product — the value of goods and services it produces annually — is about $7 trillion, second place to the United States ($13.8 trillion).

Miller acknowledges that China is becoming the manufacturing hub of the world. But if the aim is superpower status, there remains much to be done.

"China is nowhere close to becoming a world financial center," Miller says. And to become a superpower, China's "dramatic economic growth must continue indefinitely, a prospect about which there are grounds for skepticism."

Still, there's that increasingly common "Made in China" label that gives many Americans the impression of a country aiming to take over. A lot more labels would be required.

"China's rise further depends critically on the continuation of such [economic] growth rates, and there are reasons to wonder how long the spectacular rates of the past 25 years can continue," Miller says. "The high proportion of China's economy occupied by its exports makes it sensitive to the ups and downs of the international economy generally and to the engine of American consumption in particular."

Other say there's no reason, however, to expect a significant slowdown anytime soon.

"The U.S. isn't going to disintegrate into a backwater economy," said Porter, the Georgia Tech analyst. "But if you scan the contributing factors to technology-driven economic prominence, the Chinese upside is far greater. They are educating more scientists and engineers. Their government puts a high priority on technical capability and entrepreneurial activity. If you look at our educational system (especially K-12), our investment (savings rate), debt, and so on – prospects are scary."

For now at least, let the games continue.

Robert is an independent health and science journalist and writer based in Phoenix, Arizona. He is a former editor-in-chief of Live Science with over 20 years of experience as a reporter and editor. He has worked on websites such as Space.com and Tom's Guide, and is a contributor on Medium, covering how we age and how to optimize the mind and body through time. He has a journalism degree from Humboldt State University in California.