Battered Remains of Medieval Knight Discovered in UK Cathedral

The battered remains of a medieval man uncovered at a famous cathedral hint that he may have been a Norman knight with a proclivity for jousting.

The man may have participated in a form of jousting called tourney, in which men rode atop their horses and attacked one another, in large groups, with blunted weapons.

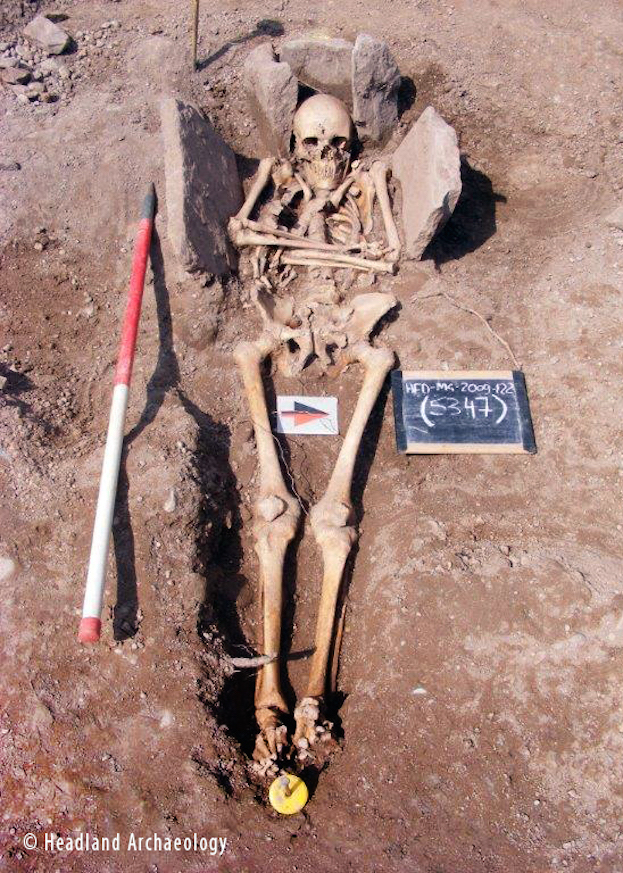

Archaeologists uncovered the man's skeleton, along with about 2,500 others — including a person who had leprosy and a woman with a severed hand — buried at Hereford Cathedral in the United Kingdom. The cathedral was built in the 12th century and served as a place of worship and a burial ground in the following centuries, said Andy Boucher, a regional manager at Headland Archaeology, a commercial archaeology company that works with construction companies in the United Kingdom.

A few years ago, the Heritage Lottery Fund, which is financed by the national lottery in the United Kingdom, awarded money to the cathedral for the landscaping and restoration of its grounds. But first, workers had to relocate the thousands of skeletons, many of which were near the ground's surface. [See Images of the Burial of Another Medieval Knight]

"By church law, anybody who died in the parish had to be buried in the cathedral burial ground," almost continuously from the time the cathedral was built until the early 19th century, Boucher told Live Science.

From 2009 to 2011, his team respectfully removed the human remains. But one stood out — a 5-foot-8-inch (1.7 meters) man with serious trauma on his right shoulder blade, 10 of his right ribs and left leg.

"He's the most battered corpse on the site," Boucher said. "He had the largest number of broken bones."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The man was about 45 years or older when he died, according to a bone analysis. He was buried in a stone-lined grave, a type of grave that was used between the 12th and 14th centuries, the researchers said.

Four of the man's ribs showed healed fractures that may have occurred simultaneously, suggesting a single instance of trauma, researchers wrote in the pathology report. Another four ribs were in the process of healing, indicating that the man was still recovering from the injuries when he died. The other two damaged ribs also show evidence of trauma, and his left lower leg has an unusual twisting break, one that could have been caused by a direct blow or a rolled ankle, according to the report.

In addition, the man had lost three of his teeth during his lifetime. A chemical analysis of his other teeth that matched different isotopes (a variation of an element) to foods and water samples from different geological locations showed that the man likely grew up in Normandy and moved to Hereford later in life, Boucher said.

Jousting battle

It's impossible to know what wounded the man, but his injuries are in line with those that nobility got through tourney, or jousting, the researchers said.

"Tourney, the true form of jousting, is open combat between large groups of people in fields — basically, a mock battle," Boucher said. "They just laid into each other with blunted weapons, which is another reason we think he might be a knight, because none of the wounds to him are caused by sharp weapons. They're all caused by blunt-force trauma."

Perhaps the man injured his leg during a horse ride during one of these tourneys, if the foot had gotten stuck in the stirrup, Boucher said. Moreover, the injuries to his right shoulder and ribs could have happened if he fell from his horse, or was hit with a blunt weapon on the right side of his body, according to the report.

However, the man may have sustained his injuries in other ways. The coroner's files show that men older than age 46 who died of accidental deaths during medieval times were likely to die while traveling or transporting goods, according to the report. [8 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries]

The archaeologists also found several other intriguing human remains, including those of a man with leprosy and a woman with a severed hand.

The man with leprosy, likely about 20 years old at the time of his death, stood about 5 feet 5 inches (1.7 m) tall. People with this disease, which causes skin lesions and nerve damage, were usually buried in separate grounds because of stigma toward the condition. But perhaps the medieval bishop at the time, known to have suffered from leprosy, felt sympathy for this person and allowed for his burial at the cathedral, Boucher said.

The researchers aren't sure what happened to the woman. The punishment for thieves of that era was to cut off their hand, but it's unclear why a thief would have been buried at the cathedral, Boucher said.

"She's a shroud burial, so she's probably medieval — sometime between 1100 and 1600," he said.

The archaeologists are storing the exhumed skeletons in a clean and dry place, and will treat them in accordance with the cathedral's wishes, Boucher said.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.