X-Ray Scans 'Dig' Beneath Layers of Rembrandt Painting

There's more than meets the eye in artist Rembrandt van Rijn's famous 17th-century painting, "Susanna and the Elders," according to a new study.

To learn more about how the Dutch painter created his masterpiece, art historians and researchers recently compared two imaging techniques that revealed hidden layers in the nearly 400-year-old painting.

The oil painting, dated and signed in 1647, hangs in Gemäldegalerie, an art museum in Berlin, Germany. The painting illustrates the biblical story of Susanna, who is caught bathing by a group of elders and is blackmailed into coming with them. In the tale, Susanna refuses, and the elders are undone by their lies. [Gallery: Hidden Gems in Renaissance Art]

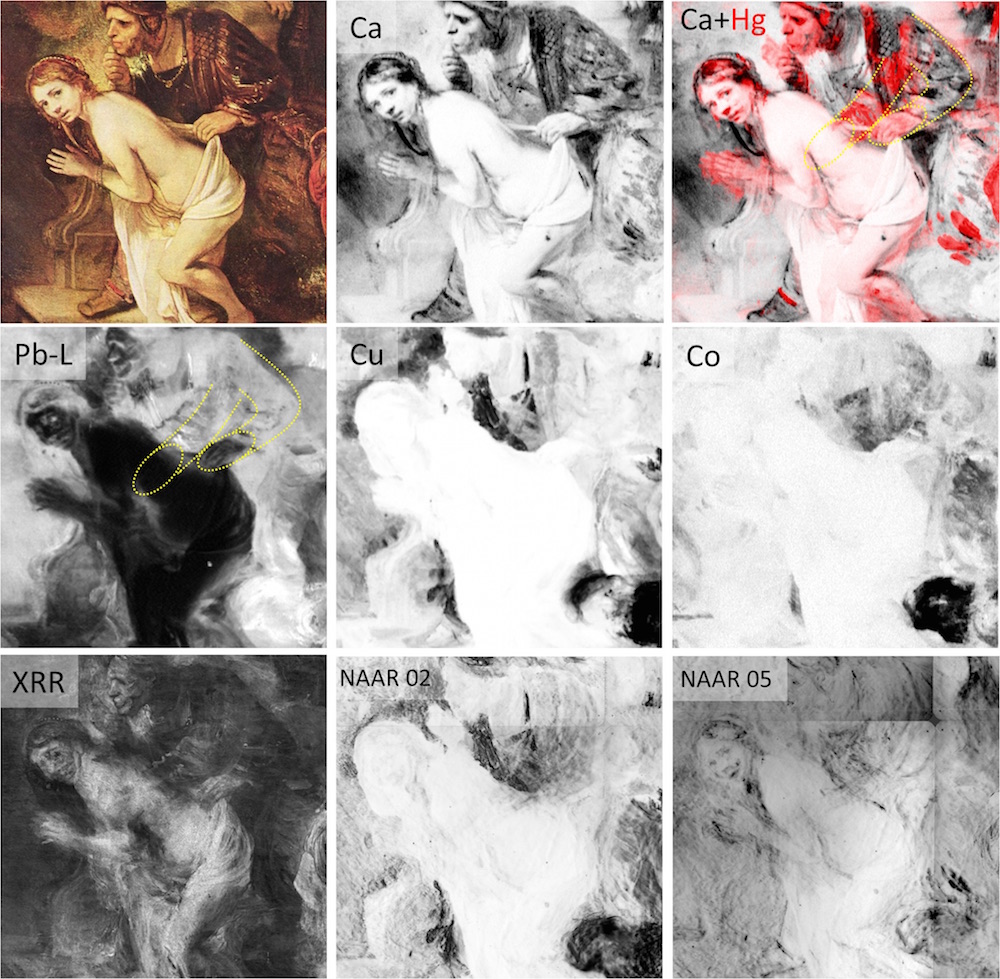

Using two imaging techniques, the researchers found that the painting has a "considerable number of overpainted features," they wrote in the study. For instance, Rembrandt redrew one of the Elder's arms from his original draft. They also identified a number of chemical elements used in the pigments, such as manganese and iron in the earth-colored pigments, white lead in the distinct whites and mercury in the painting's vermillion-red pigments.

But the researchers didn't choose to study "Susanna and the Elders" on a whim. Earlier research had already revealed that Rembrandt had labored over the painting, redrawing figures as he perfected the piece.

In the 1930s, researchers took an X-ray of the painting. The results showed that the work of art was replete with pentimenti, or changes the artist made to the painting as he carefully crafted the final scene. (Pentimenti comes from the Italian verb "pentire," which means "to repent.")

Researchers found even more concealed details in 1994, when they used neutron activation autoradiography. This technique involves using a nuclear research reactor to blast the painting with neutrons. By seeing how the neutrons interact with the painting, the researchers can determine what elements are present in the pigments, with the exception of lead-based pigments.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The painting was also small enough that the researchers of the new study could complete X-ray scans within a single day at the museum in Berlin. Then, they compared their findings with the previous scans of the painting, and tested which method provided the best results.

Interestingly, the elements identified from the X-ray scans were the easiest to interpret, the researchers said. This is likely because many of the individual elements are clearly separated in the results. This technique, known as macro X-ray fluorescence, can also be used to study a broader range of chemical elements compared to autoradiography, they said.

But macro X-ray fluorescence analysis isn't perfect. It can only detect bone black (a carbon-based black pigment) on a painting's surface, not on its underlayers, which means the scanning technique misses hidden, preliminary sketches, the researchers said.

In contrast, autoradiography is a good tool for detecting phosphorus (present in bone black) and pigments like umber (dark-yellow brown), copper-based greens and blues, smalt (blue) and vermilion. However, it's less adept at identifying calcium, iron and lead in pigments.

But, when combined with X-ray scanning, autoradiography can help detect single brush strokes — an important factor in learning about an artist's technique.

"Given the relatively short time and less effort required for investigations using X-ray fluorescence scans, this technique is expected to be applied more frequently in the future than autoradiography," study lead researcher Matthias Alfeld, a researcher at the University of Antwerp in Belgium, said in a statement.

However, Alfeld added that autoradiography is still a useful tool that can "visualize the distribution of certain elements through strongly absorbing covering layers — both methods ultimately provide complementary information. This is especially true for phosphorus, which was found present in the sketching of the painting investigated."

The study was published online Tuesday (April 14) in the journal Applied Physics A: Materials Science and Processing.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.