170-Year-Old Champagne Recovered from the Bottom of the Sea

Every wine connoisseur knows the value of an aged wine, but few get the opportunity to sample 170-year-old Champagne from the bottom of the sea.

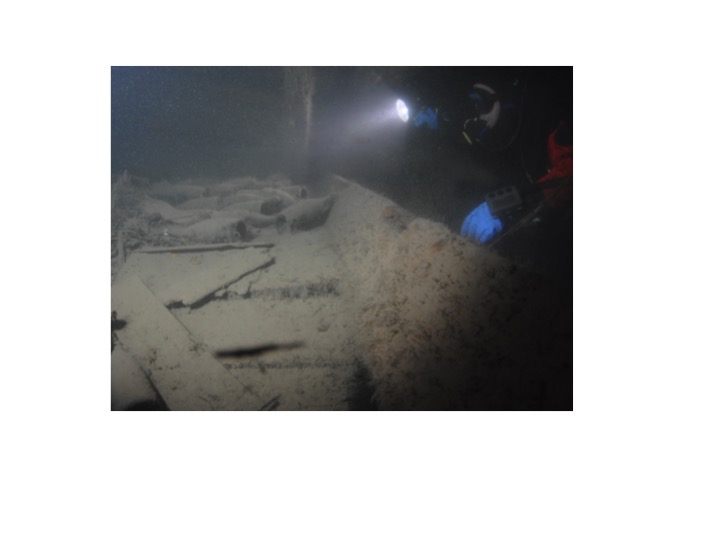

In 2010, divers found 168 bottles of bubbly while exploring a shipwreck off the Finnish Aland archipelago in the Baltic Sea. When they tasted the wine, they realized it was likely more than a century old.

A chemical analysis of the ancient libation has revealed a great deal about how this 19th-century wine was produced. [The 7 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth]

"After 170 years of deep-sea aging in close-to-perfect conditions, these sleeping Champagne bottles awoke to tell us a chapter of the story of winemaking," the researchers wrote in the study, published today (April 20) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Deep sea bubbly

In the study, led by Philippe Jeandet, a professor of food biochemistry at the University of Reims, Champagne-Ardenne in France, researchers analyzed the chemical composition of the wine from the shipwreck and compared it to that of modern Champagne.

Unexpectedly, "we found that the chemical composition of this 170-year-old Champagne … was very similar to the composition of modern Champagne," Jeandet told Live Science. However, there were a few notable differences, "especially with regard to the sugar content of the wine," he said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Engravings on the part of the cork touching the wine suggest it was produced by the French Champagne houses Veuve Clicquot Ponsardin, Heidsieck, and Juglar, the researchers said.

A chemical analysis of the wine revealed that it contained a lot more sugar than modern Champagnes. The 170-year-old beverage had a sugar content of about 20 ounces per gallon (150 grams per liter), whereas today's Champagnes have only about 0.8 ounces to 1 oz/gal (6 to 8 g/L).

This high sugar content was characteristic of people's tastes at the time, the researchers said. In fact, in 19th-century Russia, it was common for people to add sugar to their wine at dinner, Jeandet added.

"This is why Madame Clicquot decided to create a specific Champagne with about 300 grams [of sugar] per liter," which is about six to seven times the sugar content of Coca-Cola, he said.

In addition, the Champagne contained higher concentrations of certain minerals — including iron, copper and table salt (sodium chloride) — than modern wines.

The wine likely contained high levels of iron because 19th-century winemakers used vessels that contained metal, the researchers said. The high copper levels likely came from the use of copper sulfate as an anti-fungal agent sprayed on the grapes — the beginnings of what later became known as the "Bordeaux mixture."

Although one of the bottles from the shipwreck was contaminated by seawater, this is probably not the reason for the wine's high salt content. Rather, it's more likely it came from the sodium-chloride-containing gelatin used to stabilize the wine, Jeandet said.

'Spicy,' 'leathery' taste

The chemical composition closely matched the descriptions of wine-tasting experts, who described the aged Champagne as "grilled, spicy, smoky and leathery, together with fruity and floral notes."

The researchers were amazed by how well the wine had aged under the sea.The Champagne from the shipwreck was remarkably well preserved, as evidenced by the low levels of acetic acid, the characteristic vinegary taste of spoiled wine.

The wine was found at a depth of more than 160 feet (50 meters), where it's dark and exposed to a constant, low temperature — "perfect slow-aging conditions for good evolution of wine," Jeandet said.

Some winemakers are already experimenting with aging bottles of wine in seawater for extended periods.

"I'm sure there are people that are ready to spend a lot of money to have the privilege of saying to their friends, 'I put on the table a bottle that has been aged 10 years at the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea,'" he said.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.