If you've ever untangled a Gordian knot of wires and cords, or seen your 2-year-old sucking on your laptop charger, you understand the appeal of wireless charging.

Until recently, however, there weren't alternatives to charging through bulky wires and cords. But as wireless charging becomes more advanced, it may be used to power a wide variety of things other than phones or watches, such as lamps or even electric buses, experts say.

But just what is wireless charging? And why is a technology developed a century ago just now becoming popular? We talked to a few experts to find out. [Quiz: The Science of Electricity]

How it works

Wireless charging as a concept has been around since inventor and physicist Nikola Tesla first concluded that you could transfer power between two objects via an electromagnetic field, said Ron Resnick, president of the Power Matters Alliance, which has a wireless charging protocol.

Essentially, wireless charging uses a loop of coiled wires around a bar magnet — which is known as an inductor. When an electric current passes through the coiled wire, it creates an electromagnetic field around the magnet, which can then be used to transfer a voltage, or charge, to something nearby, Resnick said.

Most wireless power stations nowadays use a mat with an inductor inside, although electric toothbrushes, for example, have long had wireless charging embedded in their bases. Because the strength of the electromagnetic field drops sharply with distance (as the square of the distance between the objects), a device must be fairly close to a charging station to get much power that way, Resnick said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

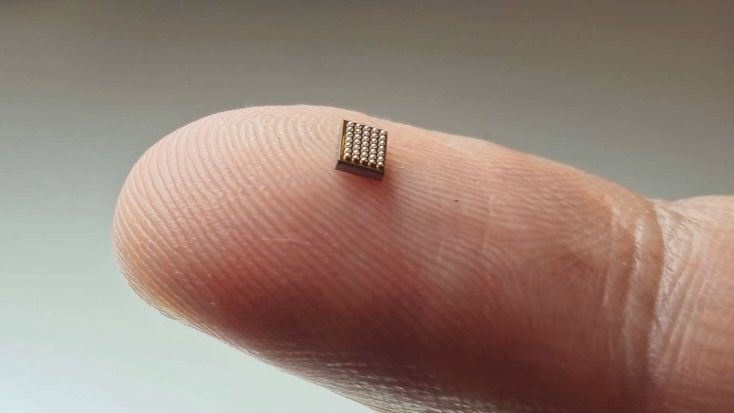

But although the basic concept of wireless charging has been understood for more than 100 years, scientists hadn't figured out a way to efficiently transfer large amounts of power using this technique, Resnick said. The amount of electric charge transferred is proportional to the number of coils that can be looped around the tiny bar magnet, as well as the strength of the magnet. Until recently, wires and electronics couldn't be made small enough and cheaply enough to make wireless charging feasible.

Improvements in technology

But that's changed in recent years.

"The cost to do it has been really reduced," Resnick told Live Science. "To make it more efficient, you have to have very, very flat coils of wire," enabling many loops of wire to be coiled around the tiny bar magnet, he said.

What's more, wireless power stations must charge only objects that are supposed to be charged, such as a phone, and not, for example, a stray penny that falls on it, Resnick said.

To ensure that the wireless charging station doesn't power an errant object, wireless power stations use tiny transmitters that communicate with small receivers in a device, such as a phone, said John Perzow, vice president of market development for the Wireless Power Consortium, which created the Qi wireless charging technology.

In essence, the receiver "talks" to the charging station, Perzow said. "If it says I'm an authorized Qi receiver, it's OK to send me some power. I'll let you know how much power I need, and as those needs change, I'll let you know. And when I'm done charging, I'll let you know so you can go back to sleep," he told Live Science.

Future uses

Nowadays, both the Power Matters Alliance and Wireless Power Consortium have developed competing protocols, or systems, for wirelessly charging devices. Existing systems are used primarily to charge smartphones or smartwatches.

But wireless power may soon extend to many more applications. For instance, electric buses in South Korea can now be charged through a wireless platform, and IKEA is rolling out a new line of furniture, including lamps and tables, with built-in charging stations.

Other groups are integrating wireless charging stations into public locations so that people with so-called battery anxiety — that ever-present fear of running out of juice — can charge their devices on the go, Perzow said.

As technology improves, it may be possible to charge bigger and more power-hungry devices, such as blenders or even vacuum cleaners, Resnick said.

And companies are already designing systems in which wireless charging platforms in hotel rooms will be able to not only charge phones, but also figure out when people are in their rooms, sync their TV to the last spot in a movie they were watching on the plane and sense whether the air conditioning should be cranked up, Perzow said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitterand Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.