Stegosaurus' Bony Plates May Reveal Dino's Sex

The plates of the Stegosaurus — the large, bony discs that lined the dinosaur's neck, back and tail in two staggered rows — may have differed between males and females, a new study finds.

An analysis of the 150-million-year-old remains of the species Stegosaurus mjosi show that some individuals had wide plates, whereas others had tall plates. These anatomical differences may distinguish males and females — a concept known as sexual dimorphism, said the study's author, Evan Saitta, a graduate student of paleobiology at the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom who began the study as part of his senior thesis at Princeton University.

"It's the most convincing evidence we have so far of sexual dimorphism in a dinosaur," excluding birds, the living descendants of dinosaurs, Saitta told Live Science. [Photos: Incredible Near-Complete Stegosaurus Skeleton]

Saitta has studied Stegosaurus fossils since 2009, when he began visiting the Judith River Dinosaur Institute (JRDI) in Montana while still in high school. The JRDI is the only known dinosaur graveyard to have multiple Stegosaurus fossils from the same time period buried together, Saitta said. He became intrigued by the dinosaurs' plates, and wondered whether the different dimensions were signs of sexual dimorphism.

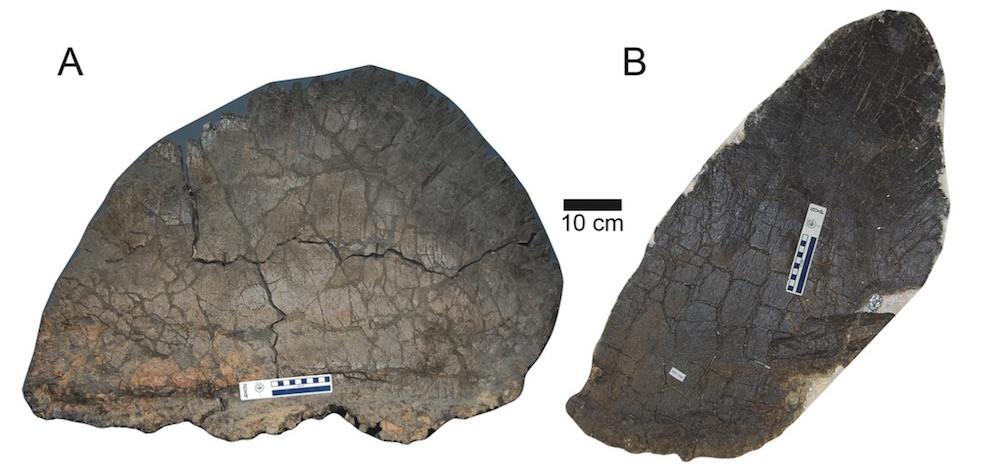

He took CT scans and measurements of 10 plates in good condition from the Montana quarry, and included 30 Stegosaurus plates from earlier research. He also looked at four tail spikes from the Montana quarry, but didn't find evidence of sexual dimorphism.

The wide plates were up to 45 percent larger in surface area than the tall plates, he found. The largest wide plate was 35.8 inches by 25.5 inches (91 centimeters by 65 centimeters). In contrast, the largest tall plate is 21.2 inches by 33.5 inches (54 cm by 85 cm), he said.

Sexual dimorphism

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Next, Saitta looked for other possible causes of the plate differences, including that they came from different species.

The dinosaur graveyard in Montana held a jumble of bones, and it wasn't always clear which plates belonged to which skeleton. Yet "every other bone is the same," besides the plates, suggesting that all of the individuals were S. mjosi, Saitta said. In addition, the dinosaurs were buried together, suggesting they lived together, he said.

"Do we have co-existence? You can't say for sure, but I wouldn't be surprised if these individuals in Montana were a social group," Saitta said.

He also checked whether the size of the plates was simply variation within individuals. But if this were the case, the plates would come in all sizes along the spectrum, from wide to tall.

"We have two distinct varieties of plates, and we don't see intermediates," he said.

He also checked whether the different sizes were a product of age. But he found one adult with tall plates and another adult with wide plates, suggesting that growth wasn't the reason for the differences.

Which is the girl?

Sexual dimorphism remained a real possibility. However, it's extremely difficult to determine the sex of dinosaurs. Some fossils can be identified as female because they contain eggs or calcium deposits in the long bones that were likely a preparation for egg laying, Saitta said. But unless these clues are present, scientists can't know a dinosaur's sex.

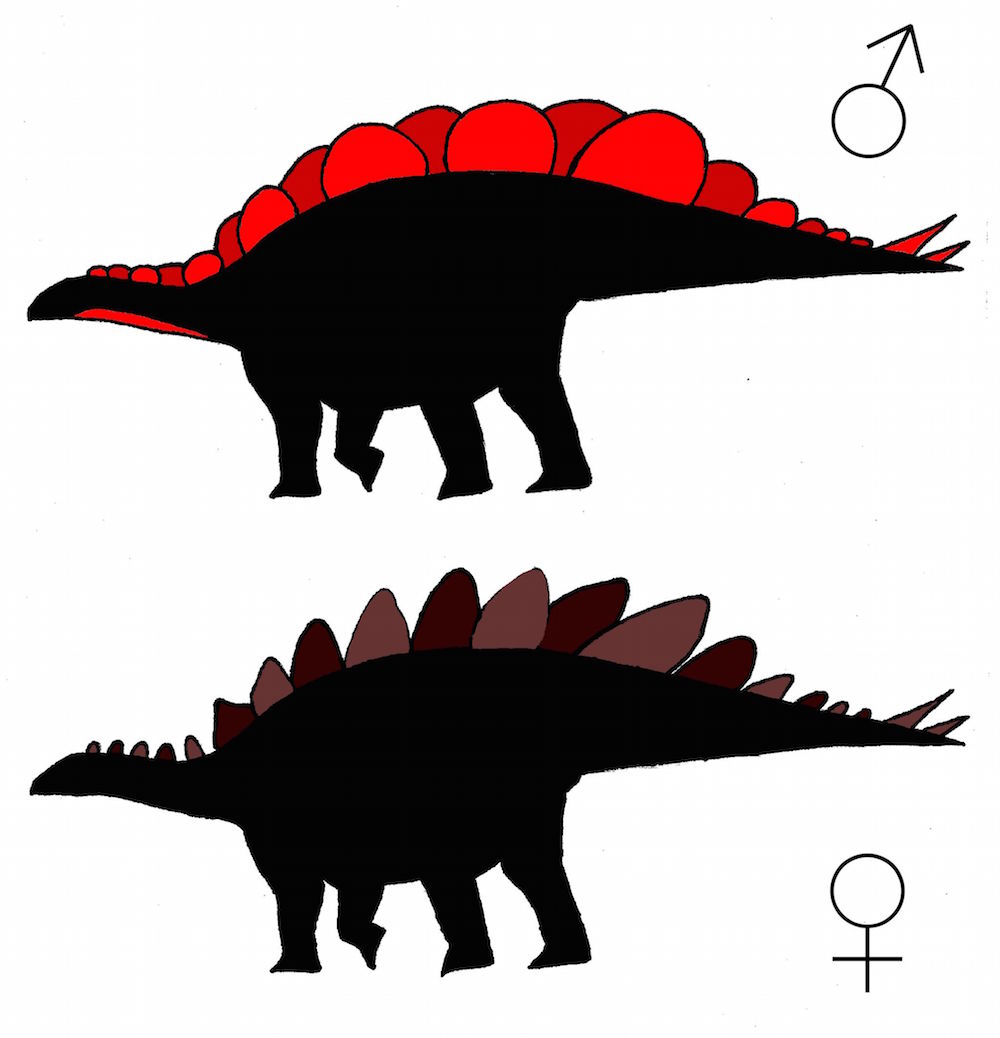

None of the Stegosaurus fossils in the study come from animals with a known sex, he said. But Saitta shared an idea in the study: Perhaps the males had the wide plates, and the females had the tall ones.

Male animals today typically invest more energy in their ornamentation than females do, and the wider plates were larger and thus would have required more energy to grow, he said. Two staggered rows of wide plates may have been attractive to females, he said. [In Photos: Baby Stegosaurus Tracks Unearthed]

The tall plates may have belonged to the females, which possibly used them as a prickly deterrent against predators, he said. The males likely didn't use the plates to fight each other, as they may have been deadly weapons, he added.

The study is "intriguing," but more work is needed before the plates can be looked at as reliable predictors of sexual dimorphism, said Andrew Farke, a paleontologist at the Raymond M. Alf Museum of Paleontology in Claremont, California, who was not involved with the study.

"One of the Holy Grails of dinosaur paleontology is trying to distinguish male and female dinosaurs," Farke said. "I think this is one of those cases that's quite suggestive. I wouldn't say it's necessarily airtight, but it's fairly suggestive of something going with these animals."

In future work, scientists could examine even more fossils, Farke said. "I would like to see additional analyses done on this," he added. "The shape analysis that was done is pretty simple. There's much more powerful analyses out there nowadays."

However, the Stegosaurus plates found in Montana could have been damaged by amateur excavators, meaning their true dimensions would never be known, said Kenneth Carpenter, director of the Utah State University Eastern Prehistoric Museum, who was not involved in the study.

But Saitta said that was not the case, and that he "personally prepared many of the plates. "One can examine the edges to see if they are broken," he said, "which is usually apparent on close inspection."

The findings were published today (April 22) in the journal PLOS ONE.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.