Washington Earthquake's Mysterious Source Discovered

PASADENA, Calif. — Geologists have finally solved a 142-year-old earthquake mystery in central Washington state.

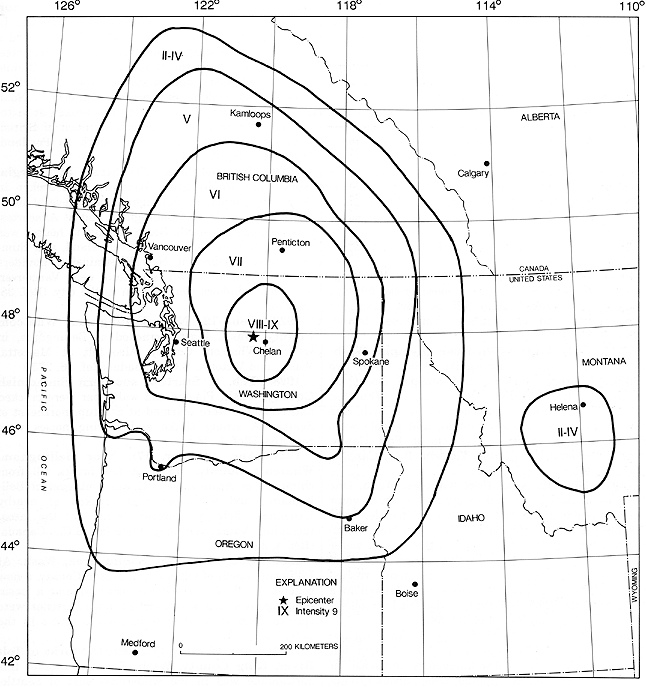

Until now, no one knew the source of a powerful earthquake that rattled windows from Washington to Montana on Dec. 14, 1872. The quake's size, based on historical accounts, was magnitude 6.8. At the time, newspapers put the epicenter in several areas, from underneath the Puget Sound north to Vancouver, British Columbia. But Washington's eyewitness reports, slower to arrive in the sparsely populated state, centered the most intense damage east of the Cascades, near Wenatchee, where a giant landslide temporarily dammed the Columbia River.

"There have been lots of controversies about where this earthquake actually occurred," said Brian Sherrod, lead study author and a research geologist with the U.S. Geological Survey in Seattle. [7 Ways the Earth Changes in the Blink of an Eye]

Using both high-tech tools and back-breaking labor, Sherrod found the 1872 earthquake fault near the town of Chelan, he reported yesterday (April 21) here at the annual meeting of the Seismological Society of America.

The new fault, which no one had ever noticed before, was named the Spencer Canyon fault, after the valley in which it was found.

Sherrod and his colleagues have been searching for the mystery fault for several years. They started their hunt near the town of Entiat, where there are ongoing swarms of small earthquakes and many faults nearby. Entiat is also close to 1872's river-clogging landslide. The USGS surveyed the area twice with lidar, an airborne laser-mapping tool that creates detailed maps of surface topography. A faint "moletrack" visible in the lidar turned out to be a fault scarp, where a fault moves the ground surface during an earthquake.

The scarp snakes along a steep hillside in the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest, west of the Columbia River. The remote, hilly terrain meant Sherrod and his colleagues had to dig two trenches across the fault by hand, because the only road was too narrow to bring in an excavator.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Fault trenches expose layers of rock or sediment that were disturbed by past earthquakes. Dating charcoal and ash in the sediments can pin down the date of these ancient events.

In one trench along the newly identified fault, Sherrod discovered a distinctive ash layer called the Mazama ash, blasted out by the volcanic eruption that created Oregon's Crater Lake more than 7,000 years ago. The ash layer is now offset from itself about 6.5 feet (2 meters) on either side of the fault, , Sherrod said.

In the second trench, the Spencer Canyon fault pushes 75-million-old gneiss (a metamorphic rock) on top of soil that has bits of charcoal just 285 years old. The young charcoal helped link the fault to the 1872 earthquake by providing a maximum age for its recent movement. Sherrod also showed the fault scarp is older than two small landslides that buried it. The oldest trees growing on top of the landslides are 130 years old, he said. Ponds created by the landslides also drowned trees, and those trees were killed sometime in the past 300 years.

"The evidence pins down the action to a window of time," Sherrod said.

Further research planned by Sherrod will reveal how often the fault has ruptured in the past, and what future hazards it presents to the many hydroelectric dams nearby. The risk to Washington's nuclear sites is less clear, because they are more than 60 miles (100 kilometers) away.

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.