Whooping Cough Outbreaks Traced to Change in Vaccine

The recent outbreaks of whooping cough in the United States may be due, in part, to a change made two decades ago to vaccine ingredients, a new study finds.

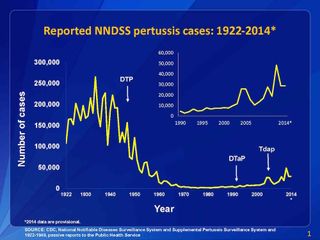

In 2012, the United States had about 48,000 cases of whooping cough (also called pertussis) — the most cases since 1955. Although the numbers dropped in 2013 and 2014 to about 29,000 cases yearly, there are still far more cases now than in decades past. Between 1965 and 2002, there were no more than 10,000 cases yearly.

Researchers have proposed a number of ideas for the increase, including increased awareness of the disease and better diagnostic techniques. Others have suggested that fewer people were getting the vaccine, and some thought that the new vaccine's ingredients were less effective.

In the new study, researchers tested these theories using mathematical models. They used an enormous data set from a variety of sources on whooping cough cases in the U.S. from 1950 to 2009. [Tiny & Nasty: Images of Things That Make Us Sick]

They found that a change in vaccine ingredients was the best explanation for the recent whooping cough outbreaks, according to the study, published today (April 23) in the journal PLOS ONE Computational Biology.

Whooping cough is caused by the bacterium Bordetella pertussis, which infects the respiratory system. The disease causes people to make a distinctive "whoop," or gasp, when they inhale after a coughing fit.

Doctors began vaccinating people against pertussis in the 1940s with a type of vaccine called a whole-cell vaccine, which was made of dead bacteria. This type of vaccine "can raise an immune response, but cannot cause the disease," said the study's lead researcher, Manoj Gambhir, an associate professor of epidemiology at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Widespread use of this vaccine dramatically cut pertussis infections. Before the 1940s, there were 150 cases of pertussis yearly for every 100,000 people in the United States, but during the 1970s, that number had dropped to an average of 0.5 cases yearly.

But the whole-cell vaccine sometimes caused side effects, such as fevers, and in some severe cases, people developed fever-induced convulsions, Gambhir said.

In 1991, researchers developed a new, "acellular" vaccine that does not contain dead bacterial cells. This vaccine "contains far fewer components of the bacteria and, therefore, far fewer possible biochemical triggers for the adverse events," Gambhir told Live Science.

Doctors began using the acellular vaccine in the U.S. during the 1990s, but it turned out to be less effective than the original vaccine: It prevents 80 percent of cases, compared with the 90 percent of cases that the whole-cell vaccine prevented, Gambhir said. This means that, of the people exposed to the disease, about 20 percent who received the acellular vaccine may still get sick, compared with just 10 percent of those who received the whole-cell vaccine.

Vaccination clues

Babies under age 1 have the highest number of pertussis cases. (Infants younger than 2 months old cannot receive the vaccine.) Young children are especially susceptible to the bacterial infection: In 2008, 195,000 children died from pertussis worldwide.

Normally, in a pertussis outbreak, a first wave of cases in infants is followed by a second "bump" of cases in adolescents. (It is thought that immunity to pertussis wanes in the teen years, so doctors recommend getting a booster shot.) But in a 2010 outbreak, researchers noticed that children ages 7 to 10 were getting whooping cough. In 2012, an outbreak that centered in Washington affected mainly 7- to 13-year-olds.

"The lower level of protection of this group of kids is well explained by the fact that they were among the first group to be entirely vaccinated by the acellular vaccine," Gambhir said. [6 Superbugs to Watch Out For]

The new study supports the idea that researchers need to develop a pertussis vaccine that is both safe and effective, said Dr. Pritish Tosh, an infectious-diseases physician at the Mayo Clinic and a member of the Mayo Vaccine Research Group, who was not involved with the study.

"In the long run, we may need to have newly designed pertussis vaccines that give a broader and longer-lasting protection," he said.

In the meantime, people should continue to get the current vaccine to protect not only themselves, but also infants who haven't received the vaccine yet and people whose immune systems are compromised, Tosh said. Pregnant women can also receive a booster shot during their third trimester to protect the fetus, he added.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.