Early Urban Planning: Ancient Mayan City Built on Grid

The city's grid system has never been seen in the Maya world before and was likely designed by a very powerful ruler thousands of years ago, the researchers said.

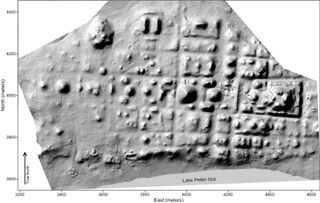

An ancient Maya city followed a unique grid pattern, providing evidence of a powerful ruler, archaeologists working at Nixtun-Ch'ich' in Petén, Guatemala, have found.

The city, which contains flat-topped pyramids, was in use between roughly 600 B.C. and 300 B.C., a time when the first cities were being constructed in the area. No other city from the Maya world was planned using this grid design, researchers say. This city was "organized in a way we haven't seen in other places," said Timothy Pugh, a professor at Queens College in New York.

"It's a top-down organization," Pugh said. "Some sort of really, really, powerful ruler had to put this together."

The ancient Mexican city of Teotihuacan also used a grid system. But that city is not considered to be Mayan, and so far archaeologists have found no connections between it and the one at Nixtun-Ch'ich', Pugh said. [In Photos: Mayan Art Discovered in Guatemala]

People living in the area have known of the Nixtun-Ch'ich' site for a long time. Pugh started research on it in 1995 and has been concentrating on Mayan remains that date to a much later time period,long after the early city was abandoned. However, in the process of studying these later remains, his team has been able to map the early city and even excavate a bit of it.

Ceremonial route

From the mapping and excavations, Pugh can tell that the city's main ceremonial route runs in an east-west line only 3 degrees off of true east. "You get about 15 buildings in an exact straight line — that's the main ceremonial area," he said. These 15 buildings included flat-topped pyramids that would have risen up to almost 100 feet (30 meters) high. Visitors would have climbed a series of steps to reach the temple structure at the top of each of these pyramids.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

At the end of the ceremonial way, on the eastern edge of the city, is a "triadic" structure or group, which consists of pyramids and buildings that were constructed facing each other on a platform. Structures like this triadic group (the name comes from the three main pyramids or buildings in the group), have been found in other early Mayan cities.

The residential areas of the city were built to the north and south of the ceremonial route and were also packed into the city's grid design, Pugh said.

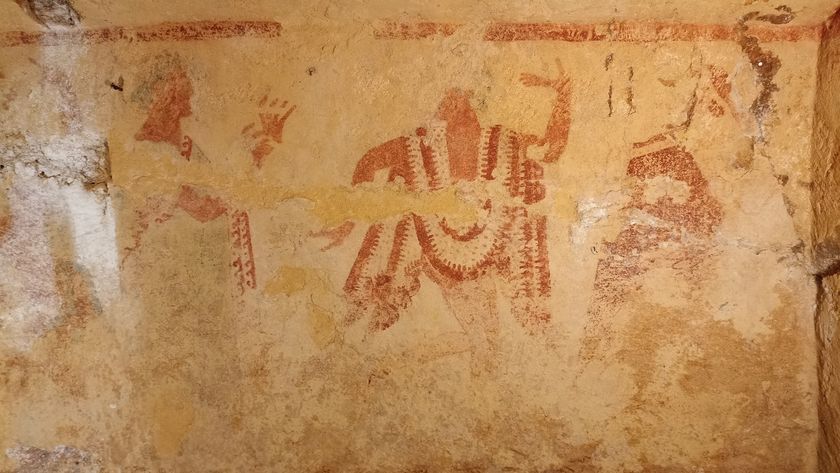

From the excavations, archaeologists can tell that many of the city's structures were decorated with shiny white plaster. "It was probably a very shiny city," Pugh said.

The city's orientation, facing almost directly east, would have helped people follow the movements of the sun, something that may have been of importance to their religion.

A wall made of earth and stone also protectedthe city, suggesting defense was also a concern of these Mayans.

Were the people miserable?

While the city was a sight to behold, its people might not have been happy with it, Pugh said.

"Most Mayan cities are nicely spread out. They have roads just like this, but they're not gridded," said Pugh, noting that in other Mayan cities, "the space is more open and less controlled."

Cities in early Renaissance Europe that adopted rigid designs were often unpleasant places for their residents to live, Pugh said. It's "very possible" that the residents of this early Mayan city "didn't really enjoy living in such a controlled environment," Pugh said.

Preserving the city

Archaeologists said they are thankful to the cattle ranchers who own the land the site is on and are protecting it against looters, Pugh said.

This location is one of the few Mayan sites in the area that hasn't been looted, and that's because the ranchers are "really protective, and they don't want people messing with the Maya ruins," Pugh said.

Additionally, the ranchers use a type of quick-growing grass, which, in addition to helping feed cattle, also protects the site from erosion, helping preserve it.

Pugh's team presented their research recently at the Society for American Archaeology's Annual Meeting, in San Francisco.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

Most Popular