Colorado Plague Outbreak Shows It's Hard to Diagnose the Disease

Doctors and veterinarians in the southwestern United States should keep an eye out for cases of plague, according to a new report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

During the summer of 2014, four people in Colorado became ill with pneumonic plague, in the United States' largest outbreak of the illness since 1924. Pneumonic plague is a very rare disease caused by the same type of bacteria as the bubonic plague, which is perhaps best known for causing the Black Death in Europe during the Middle Ages. In people with pneumonic plague, the bacteria infect the respiratory system.

In the cases in Colorado, three of the people were initially diagnosed incorrectly, and the fourth, without knowing why she was sick, had self-medicated with antibiotics, the report found.

All four people have since recovered, but a veterinarian euthanized the 2-year-old American pit bull terrier that got the deadly bacterial infection in June and had passed it on to its owner and at least two of the other infected people. [Pictures of a Killer: Plague Gallery]

The fourth person may have caught pneumonic plague from the dog's owner, which would make it "the first instance of possible human-to-human transmission" in the United States in 90 years, according to the CDC report, released today (April 30).

The outbreak started with a 28-year-old man, who developed a fever and began coughing up blood on June 28. Doctors diagnosed him with pneumonia, and a test indicated that the bacterium Pseudomonas luteola was to blame. However, some of the doctors questioned the results because they knew the bacterium that causes plague, Yersinia pestis, can often be mistaken in tests for P. luteola.

A second test one week later confirmed that the man had pneumonic plague. Doctors gave him broad-spectrum antibiotics and hospitalized him for 23 days until he recovered.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It's likely the man caught pneumonic plague from his dog, which had shown symptoms including a fever, jaw rigidity and drooling, and had problems walking and breathing. The man had the dog humanely euthanized. Once doctors realized that the man had pneumonic plague, they ordered a test of the dog's remains, and found that it tested positive for plague bacteria, according to the report.

The veterinarian who treated the dog also got pneumonic plague, but was incorrectly diagnosed with bronchitis. Another person had contact with the dog's body as well as its owner, and was initially diagnosed with pneumonia, but not plague. A veterinary clinic employee got sick too but self-medicated with antibiotics.

Plague by the numbers

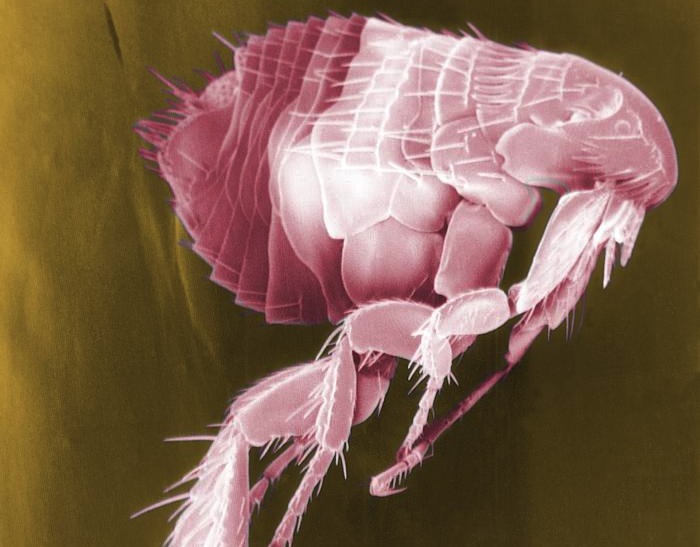

Though rare, plague is a life-threatening disease. About eight people get plague in the United States every year, primarily in the semirural regions of New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado and California, according to the report. Typically, people get sick if infected fleas on rodents bite them, or if they have direct contact with the wounds or bodily fluids of infected animals, the researchers said.

Bubonic plague is the most common type of the disease, accounting for about 85 percent of reported cases. It's known for causing fever and painful "buboes," or swollen lymph nodes. Pneumonic plague can develop if someone with bubonic plague goes untreated, or if someone inhales droplets from an infected person's cough or sneeze.

Pneumonic plague kills about 93 percent of people who catch it if they don't receive medical treatment, the researchers said. But it's also very uncommon: The U.S. had 74 reported cases of pneumonic plague between 1900 and 2012, the researchers said.

Doctors and veterinarians can learn several lessons from the Colorado outbreak, the researchers said.

"Early recognition of plague, especially the pneumonic form, is critical to effective clinical management and a timely public health response," the researchers said in the study. "Veterinarians should consider plague in the differential diagnosis of ill domestic animals, including dogs, in areas where plague is endemic."

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.