Aili Kang is director of the China Program for the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), where she has worked for 16 years. In 2008, Kang received the Global Young Conservationist Award from the Society of Conservation Biology. Kang contributed this article, as part of a series from WCS on women in conservation, to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

The work of conservationists is not limited to field investigations and peer-reviewed papers. Though I'm a trained scientist, social media is my platform, and that platform can have a significant impact on conservation. Web posts in China, paired with government and local community support, are convincing Chinese consumers to avoid the ivory trade, the most devastating threat African elephants face. Despite the thousands of miles separating the continents of Asia and Africa, Chinese chat sites can make a difference for elephants.

China is one of the largest markets for body parts from endangered wildlife, and that market has rapidly increased due to the nation's booming economy. Elephant ivory, often intricately carved, is among the most coveted of those animal products — in large part due to the high social status it has traditionally conferred to its owner. [Crushing the Ivory Trade in China (Photos)]

Because the slaughter of Africa's elephants is taking place far from most Chinese citizens, too many ignore this growing crisis. According to "The Ivory Road Study" published by National Geographic in December 2012, only 44 percent of respondents knew ivory comes from dead elephants, although consumers are more aware of this relative to non-purchasers (but they still buy). More than one-third of all respondents (36 percent) do not know that ivory trading is illegal.

This factor of geography is compounded by the sanitized and superficial presentation of retail ivory, which is associated with prestige, wealth and beauty. Associating these elements and images with the brutal reality of ivory poaching is challenging.

Ivory only comes from dead elephants

My team from the WCS China Program, along with our Chinese and international partners, have been working collaboratively to dispel such myths — and there are welcome signs that we are making progress. More and more Chinese people are at least talking about elephant poaching. Two years ago, they weren't.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

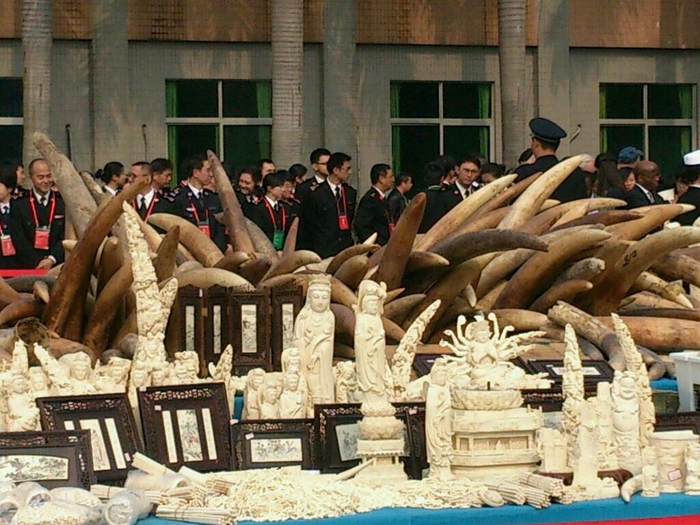

After Chinese officials destroyed six tons of ivory in January 2014, we browsed both Chinese and Western social media sites to gauge the different responses. On U.S. Twitter, people celebrated the government's action. On Chinese social media sites — mainly Sina Weibo, China's hybrid version of Facebook and Twitter, and WeChat, a hybrid of Facebook and WhatsApp — people instead were asking why officials were paying attention to this issue when there are other pressing troubles in the country, like air pollution, water pollution and food security.

Based on feedback from social media channels, we can filter and identify what topics people are concerned about, what people think about elephants and the ivory trade, who can be allies in fighting that trade, and who will need more information for the campaign to make an impact.

Combing the data for leads

Through data analysis, our team can design key messages for different audiences, from people regularly traveling between Africa and China, to people who are interested in art collection, to people who want to contribute to elephant conservation. When I discuss ivory crushes — where governments destroy illegal animal products, literally by crushing them — it's more about marketing and public relations than about scientific discourse.

Strategic partnerships with mainstream and digital media outlets have also assisted us in our efforts to educate citizens in the primary markets for ivory and other endangered animal products: China and the United States.

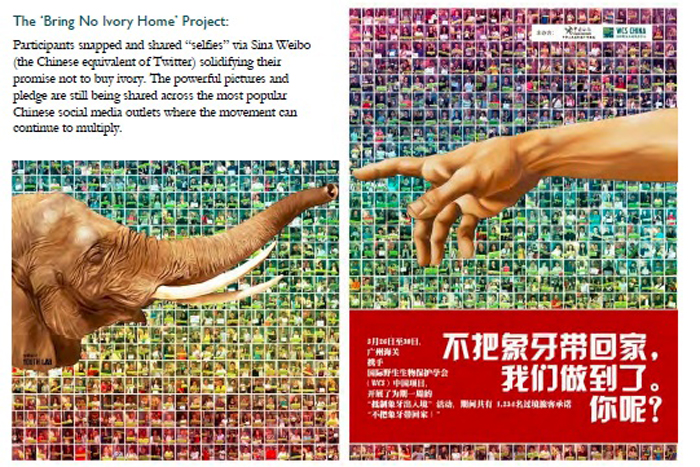

WCS's 96 Elephants campaign began in 2013, aiming to bolster the protection of elephants and educate the public about the link between ivory consumption and elephant extinction. Through this campaign, we have had more than 8,000 Chinese sign the "Bring No Ivory Home" pledge. The 96 Elephants campaign has generated close to 235 million exposures through social and traditional media in China.

Finally, we're working with the Chinese Wildlife Conservation Association — a government organization whose mission is "to promote the development of Chinese wildlife conservation," — to develop a mobile-based app called Wildlife Guardian to help Chinese law enforcement officials identify wild animals and products being smuggled into China. The app has strong support from the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) Management Authority of China, and currently we have introduced it in four out of 23 provinces.

The app will assist Chinese customs officers in identifying 500 of the most commonly traded species and products in China, from elephant ivory to big-cat claws.

Evaluations from frontline enforcement users are strongly positive. For example, officers from Guangxi Forestry Police use the app regularly whenever identification of unknown products or species is required, and they have made a number of seizures as a result. Customs authorities in Guangdong have requested that WCS provide regular training for frontline officers on how to use the app, as it is invaluable for rapid and accurate identification of illegal wildlife. And, WCS has established a good relationship with the primary training facility for forest police in China and we are looking at how the Guardian app could become an established element in the national curriculum for Chinese police. [Google Goes Wild: How Off-Road Tech Aids Conservation ]

When it comes to the illegal wildlife trade, we're committed to stopping the killing, stopping the trafficking and stopping the demand. By simultaneously collecting intelligence on the illicit ivory trade and reaching out to Chinese consumers in new ways to educate them on the poaching crisis, we are hopeful we can slow the slaughter of elephants and ensure their survival long into the future.

Read more about women in conservation in "Will Mobile Labs Finally Halt Killer Frog Fungus? (Op-Ed )" and "Voices of Rare 'Talking' Turtles May Prevent Their Extinction ." Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.