People Are Healthier in the Summer (and Here's Why)

The activity of human genes changes with the seasons, and with it, immunity changes too, according to a new study.

Seasonal changes in gene activity mean that the immune system revs up inflammation in the winter, researchers found. This may help explain why the symptoms of inflammation-related conditions — such as heart disease and rheumatoid arthritis — often worsen in winter, and why people tend to generally be healthier in the summer.

"Our results indicate that, in the modern environment, the increase in the pro-inflammatory status of the immune system in winter helps explain the peak incidences of diseases that are caused by inflammation, by making people more susceptible" to inflammation's effects, said study co-author Chris Wallace, a genetic statistician at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom.

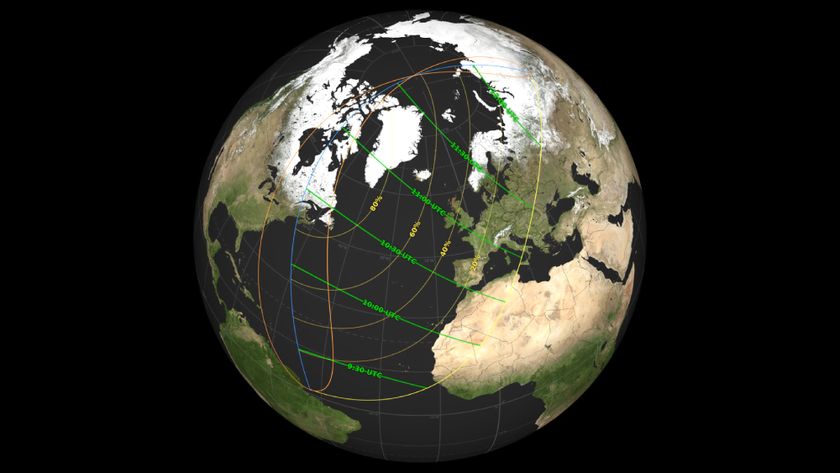

In the study, researchers examined genetic data from blood samples and fat tissue of more than 16,000 people who lived in both the northern and southern hemispheres, in countries that included the United Kingdom, the United States, Iceland, Australia and The Gambia.

The researchers found that the activity of almost a quarter of all human genes — 5,136 out of 22,822 genes tested in the study — vary over the seasons. Some genes are more active in the summer, whereas others are more active in winter, the researchers found. [11 Surprising Facts About the Immune System]

These seasonal changes in gene activity also seem to affect people's immune cells and the composition of their blood, the researchers found.

For example, during the Northern Hemisphere's winter, the immune systems of the people living there had pro-inflammatory profiles, and the levels of proteins in their blood that are linked to cardiovascular and autoimmune diseases were increased, compared with their levels during the summer.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This may explain why the incidence and symptoms of some diseases tied to increased inflammation — including cardiovascular disease, autoimmune diseases such as diabetes and psychiatric disease — peak in winter, according to the study.

In contrast, one gene, called ARNTL, was more active in the summer and less active in the winter. Previous studies on mice have shown that this gene suppresses inflammation, which may also help explain why people's levels of inflammation tend to be higher in the winter than in the summer, the researchers said.

The seasonal variation in the immune system's activity may have evolutionary roots, Wallace said. "Evolutionarily, humans have been primed to promote a pro-inflammatory environment in our bodies in seasons when infectious disease agents are circulating," she told Live Science. This pro-inflammatory environment helps people fight infections, Wallace added.

"It makes sense that our immune systems adapt to cope with variation in infections as these are thought to be the main cause of human mortality for most of our evolutionary history," Wallace said.

But even though this immune response helps fight off infection, it worsens other conditions related to inflammation.

It is not clear what mechanism brings about the seasonal variation of human immune system activity, the researchers said. However, it may involve the body's so-called circadian clock, which helps regulate sleeping patterns and is partially controlled by changes in daylight hours, the researchers said.

"Given that our immune systems appear to put us at greater risk of disease related to excessive inflammation in colder, darker months, and given the benefits we already understand from vitamin D, it is perhaps understandable that people want to head off for some 'winter sun' to improve their health and well-being," study co-author John Todd, a professor in the department of medical genetics at the University of Cambridge, said in a statement.

The new study was published today (May 12) in the journal Nature Communications.

Follow Agata Blaszczak-Boxe on Twitter. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.