Cloudiest Places on Earth Revealed in Stunning New Image

"No more cloudy days," The Eagles promise to a new love interest in the 2006 song of the same name. Keeping that promise might require going off-planet.

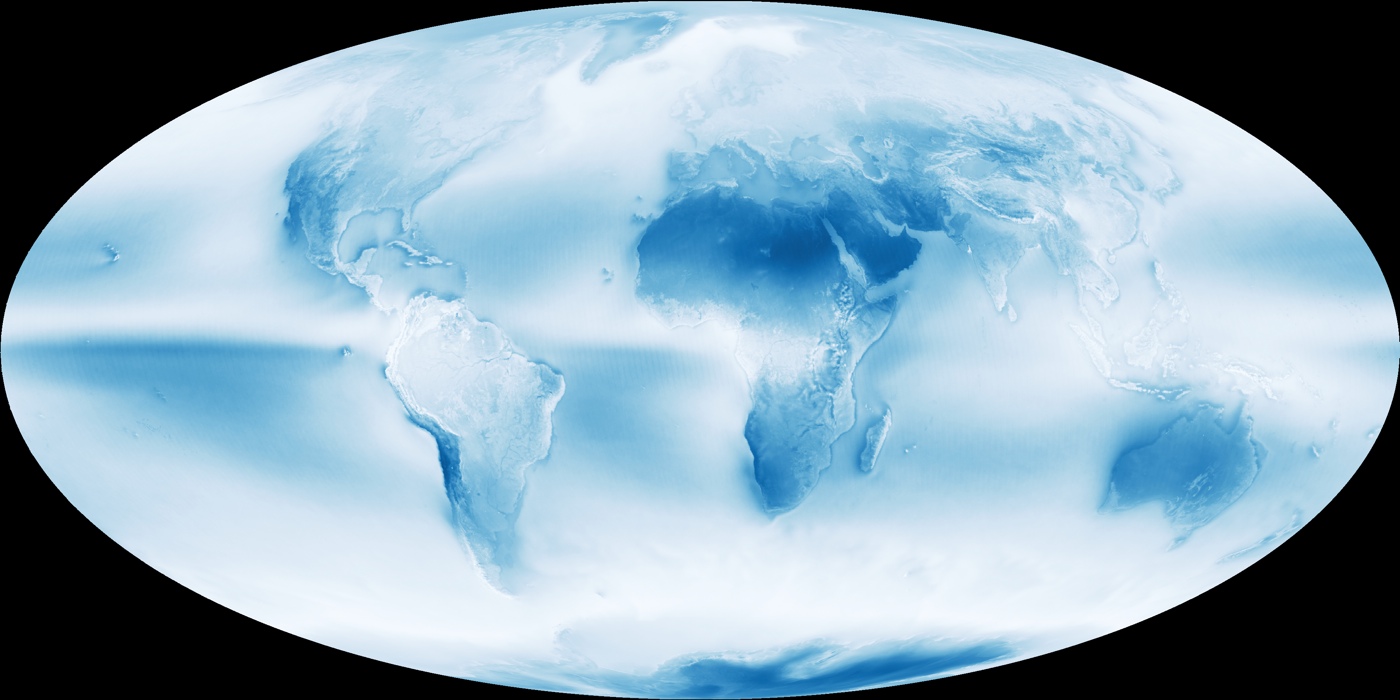

As a new NASA image reveals, the Earth is a cloudy place. According to the space agency, clouds cover about 67 percent of the Earth's surface at any given time, and less than 10 percent of the skies over the ocean are sunny and blue. Now, more than a decade's worth of data from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA's Aqua satellite reveals where clouds gather and where skies tend to be clear.

The blue-and-white image averages daily cloud observations from the satellite between July 2002 and April 2015. It reveals a mostly hazy Earth with three especially cloudy zones.

These zones are linked to the global circulation patterns in Earth's atmosphere. According to NASA's Earth Observatory, in the mid-latitudes, polar air masses collide with Ferrel cells, which circulate air westward at high altitudes and eastward at the surface. These patterns cause air to rise around 60 degrees north and south of the equator, promoting the formation of clouds in these two zones. These same patterns push air downward between 15 degrees and 30 degrees from the equator, resulting in the cloud-free zones seen in desert areas such as Australia and northern Africa.

The third particularly cloudy zone is found over the equator, where circulation cells called Hadley cells dominate. In these zones, warm air rises and condenses, creating both clouds and storms, according to the Earth Observatory.

On the satellite image, these cloudy zones are seen in bright white; the bluer the region, the clearer the skies.

In addition to illuminating Earth's cloud cover, satellites have helped alter the very definition of clouds. In research presented in 2005at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union, atmospheric scientists argued that the old categories for clouds — cirrus, stratus and cumulus — are good enough for classifying clouds by their shape as seen from the ground, but fail to take into account factors such as texture and altitude of formation, which are more readily captured by satellite imagery.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.