Squid 'Sees' with Its Skin (No Eyes Needed)

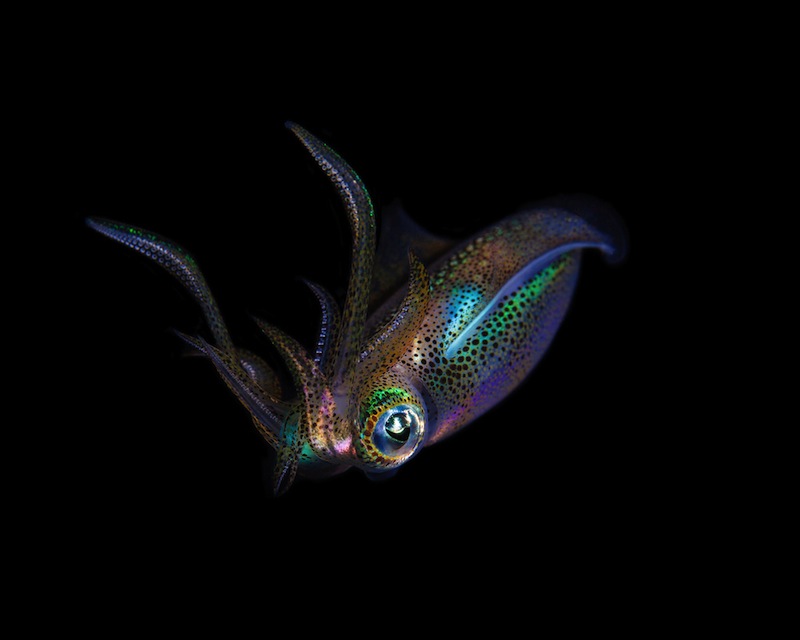

Squid, cuttlefish and octopuses are masters of camouflage, capable of changing their skin colors and patterns in the blink of an eye. And they may not even need their eyes to do it.

Two new studies, published this week in the Journal of Experimental Biology, find that cephalopod skin is chock-full of light-sensing cells typically found in eyes that help them "see." The cells likely send signals to alter skin coloration without involving the central nervous system, the researchers said.

"It may be that the patterning is just generated directly on the spot, just by the cells," said Tom Cronin, a biologist at the University of Maryland and an author of one of the studies. Understanding how could aid in the development of automatic camouflage clothing that could change color based on its background. [7 Clever Technologies Inspired by Nature]

Local control

Cephalopods are known to have sophisticated visual systems, though the vast majority of squid, cuttlefish and octopuses are colorblind. There was also tantalizing evidence that cephalopods might have light-sensing cells outside of their visual systems. For example, the bioluminescent Hawaiian bobtail squid has proteins related to vision in its light-emitting organ. And a 2010 study published in the journal Biology Letters found light-responsive proteins called opsins in cuttlefish skin.

In a new study, Cronin's graduate student Alexandra Kingston conducted an extensive molecular investigation of the skin of the longfin inshore squid (Doryteuthis pealeii) and two cuttlefish species (Sepia officinalis and Sepia latimanus). She found photosensitive proteins widespread throughout all three.

"All the evidence points to the fact that the entire phototransductive system is present in the chromatophore cells," Cronin told Live Science. The finding is exciting because chromatophores are responsible for cephalopods' color-changing abilities. Essentially, these animals can contract and dilate tiny muscles in their skin to expand or shrink skin- pigment cells. The new research suggests that control of this process is at least partly localized to the skin itself.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"They might actually have a way of directly measuring the kinds of light that are reflecting off the surfaces around the animal," Cronin said.

Missing link

In a second study, researchers at the University of California, Santa Barbara, collected skin samples from California two-spot octopuses (Octopus bimaculoides) and shone various wavelengths of light on the skin. Completely independently, the skin responded by changing colors.

Further investigation revealed that visual proteins were present in these octopuses' skin, too. The skin responded most swiftly to certain wavelengths of blue light, the researchers reported.

Next, Cronin said, scientists need to examine what happens between the cephalopod skin sensing the light and changing color.

"We have a direct connection between sensing and color production," he said. "The link we don't have is how one connects to the other."

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.