Plastic Does Decay, Creating a Crisis for 20th-Century Art

This article was originally published on The Conversation. The publication contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Because conservation scientists strive to shed light on an artist’s processes and materials choices, our work can be like that of a detective.

Using advanced scientific techniques, we have to analyze the physical and chemical properties of works of art. But we must also sift through historical and archival documents for specific mentions of materials or technologies, and how they’ve been traditionally used.

I was part of a team of scientists from The Northwestern University/Art Institute of Chicago Center for Scientific Studies in the Arts (NU-ACCESS) that collaborated with Guggenheim Museum conservators Carol Stringari and Julie Barten.

We wanted to investigate the materials and techniques employed by the prominent Bauhaus artist László Moholy-Nagy (1895-1945). Throughout his career, the Hungarian artist explored a large variety of media – including many newly-developed industrial plastics – to experiment with transparency and reflection.

For this reason, I found myself immersed in, among all things, the history of plastics – and their messy nomenclature.

Along the way, we discovered a key error in the description of one of Moholy-Nagy’s primary materials – a mistake that, had it gone unnoticed, could have resulted in the deterioration of the painting Tp 2.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The plasticity of names

Historically, it’s common for chemical products to be renamed.

We all agree that Aspirin sounds lighter and far more pronounceable than its ponderous chemical name, acetylsalicylic acid. Same with the clipped sounding Super Glue and Teflon – which are technically called cyanoacrylates and polytetrafluoroethylene, respectively.

Beginning at the end of the 19th century, the growing chemical industry made a number of new plastics with unexceptional chemical names. These were then rebranded for public consumption. Phenol formaldehyde resin became Bakelite, while cellulose nitrate was called celluloid. Objects formed from polymethyl methacrylate came to be known as plexiglas.

Unfortunately, the rebranded versions often have zero connection with their original materials. Different plastics can be lumped together under an umbrella term. This can prove problematic for understanding the history of our materials, including those used in artwork.

Not surprisingly, I ran across my own problems with “brand-ification” when I started investigating Moholy-Nagy’s paintings – specifically, Tp 2 (1930), where the artist painted bold geometric shapes on an opaque sheet of thick, blue plastic.

Mamma Mia!

The painting appeared to be in excellent condition. It made sense, then, that museum records described the plastic as a phenol-formaldehyde resin called Trolitan – the German equivalent of Bakelite, a synthetic plastic known for its long-term stability.

However, this general impression changed very quickly when NU-ACCESS’s co-director Francesca Casadio performed an on-site analysis of Tp 2.

“Mamma mia!” she exclaimed; the substrate was actually cellulose nitrate, a totally different type of early plastic – and one prone to severe degradation.

Now we needed to learn more about the true origin and formulation of the blue plastic background.

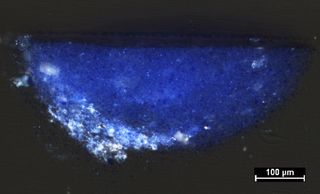

Guggenheim conservator Julie Barten provided me with a micro-sample – invisible to the naked eye – from the back of Tp 2 to enable me to examine the plastic in more detail and learn more about its condition. After preparing the sample as a cross-section, I analyzed it using scanning electron miscroscopy, which revealed that the plastic was filled with a remarkably high amount of gypsum.

Tro-lling for answers

Using this information as a guide, I researched cellulose nitrate German manufacturers of the 1930s and determined that the plastic used in Tp 2 was, in fact, a material called Trolit F, a highly filled cellulose nitrate plastic produced at the Rheinisch-Westfälischen Sprengstoff-Fabriken (RWS) company in Germany.

Delving into the company records, I discovered that the RWS company originally produced explosives for the German army during World War I, but turned to plastic manufacturing in the postwar years. RWS would develop a large variety of plastic products, all with the prefix “Tro”: Trolit F, Trolit W, Trolon, Trolitan, Trolitul, etc.

The prefix, I learned, was derived from Troisdorf, the town where RWS was incorporated near Cologne. RWS used it much like how Apple employs the letter “i” in its iPod, iPhone and iPad products.

While the Tro-line of products certainly had a nice commercial ring, it completely obscured the chemical identity of the plastic. Trolit F and Trolit W, for instance, are two distinct types of plastic. Each has different properties and uses.

Even more confusing, advertisements from the era show that they were both sold by the company under the single name of Trolit. So it’s entirely possible that customers didn’t know which type of plastic they had purchased.

Meanwhile, the media further obscured the true identity of these plastics. A 1936 special issue of the avant-garde magazine Telehor had been dedicated to Moholy-Nagy’s art. However, in the magazine – which was issued in four languages – editors spelled Trolit differently in each of the four editions: “Trolit” (German), “Trolite” (English), “Trolithe” (French) and “Trolitem” (Czech).

Lost in translation

When researching this piece, I became convinced that Moholy-Nagy knew he was using Trolit material for Tp 2, since he mentioned it by name in his writings. He also used Trolit wall panels with the same elongated proportions in his room design for the Paris Werkbund exhibition in 1930.

However, at the same time, a close examination of Moholy-Nagy’s correspondence suggests that the artist incorrectly thought that the names “Trolit” and “Bakelite” were interchangeable – and this may be at the root of subsequent misclassification of the material composition of Tp 2.

From the different sources of information available, the specific origin of the confusion surrounding Tp 2 might be traced back to 1937, when the painting entered the Solomon R Guggenheim collection.

As mentioned earlier, the material used for Tp 2 was originally (almost) accurately described as “Trolite” in the 1936 issue of Telehor magazine. But upon joining the museum collection, the material was instead described as Bakelite.

Museum records of Tp 2 show that Bakelite was later re-translated as the material Trolitan – RWS’s version of Bakelite.

This would have been consistent with the painting title, since Moholy’s titles often reference support materials. For example, his paintings Al 3 and Cop I were done on aluminum (Al) and copper plate (Cop).

Our materials research has added new pieces to this puzzle. We’ve linked the Tp 2 plastic base to the highly-filled cellulose nitrate Trolit F from RWS. It’s also conceivable that “Tp” refers to “Trolit poliert” or “Trolit Platte” – “polished Trolit” or “Trolit panel” in German.

Because cellulose nitrate plastics can deteriorate quite extensively, they require specific care and storage conditions to preserve them. And Tp 2 – long thought to be supported by the sturdy Bakelite – will now need to be cared for appropriately, especially by designing optimal conditions for storage.

As this story shows, it’s crucial to correlate archival and historical information with scientific analysis. By identifying – and correcting – misleading language, conservators can better care for iconic works of art.

Johanna Salvant is Postdoctoral Fellow at the Center for Scientific Studies in the Arts at Northwestern University.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.