Modern Human Leg Mummified Using Ancient Egyptian Methods

The ancient Egyptians famously mummified the dead to preserve their loved ones in perpetuity, and now, scientists have mummified fresh tissue from a human corpse to gain insight into these ancient preservation techniques.

The team adhered to ancient Egyptian techniques to mummify part of the human body, which had been donated to science. They placed the tissue in a salt solution, and measured the progress of preservation using state-of-the-art microscopy and imaging techniques.

The findings, detailed Friday (May 22) in the journal The Anatomical Record, give researchers some fascinating new clues about the ancient Egyptian embalming process.

"We wanted to have an evidence-based methodology" for understanding what the mummification process looked like, said Christina Papageorgopoulou, one of the researchers on the new study and a physical anthropologist at the Democritus University of Thrace in Greece. "The only way you can do this is by [doing] the experiment yourself." [See photos of mummification in progress]

Making a mummy

Most of what scientists know about ancient Egyptian mummification comes from the Greek historian Herodotus, who lived during the fifth century B.C. First, embalmers would have removed the dead individual's organs — including the brain, which would be extracted through the nose. Then, they would sterilize the chest and abdominal cavities, before placing the body in a salty fluid containing natron — a mixture of soda ash and sodium bicarbonate — which would drain the bodily fluids and prevent the body from rotting. Finally, they would swaddle the body in strips of linen and bury it in a tomb or grave.

Some studies have attempted to use these techniques to mummify animals or human organs, and there have been one or two attempts to mummify a complete human body. But the process had never been studied using modern scientific techniques while the mummification was in progress.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

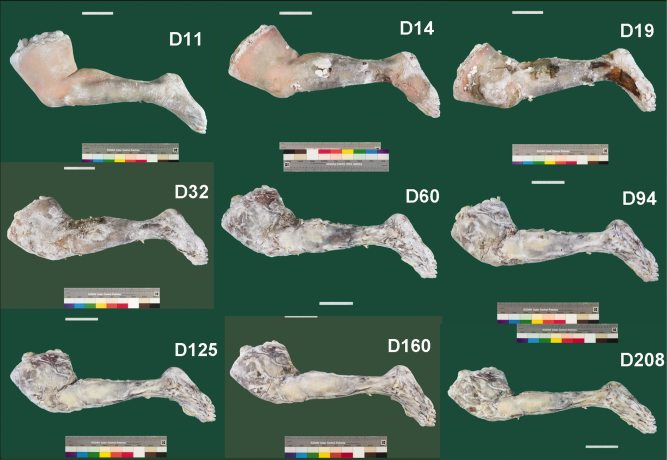

In this new study, Papageorgopoulou and her colleagues used the Egyptian salt-based preservation method to mummify the leg of a female human body that had been donated to the University of Zurich in Switzerland, where the experiment was conducted. "If we used the whole body, we would have had to cut it up and take out the intestines [and other organs]," Papageorgopoulou told Live Science.

For comparison, they also attempted to mummify a limb "naturally," using dry heat, but that attempt failed and was stopped after a week.

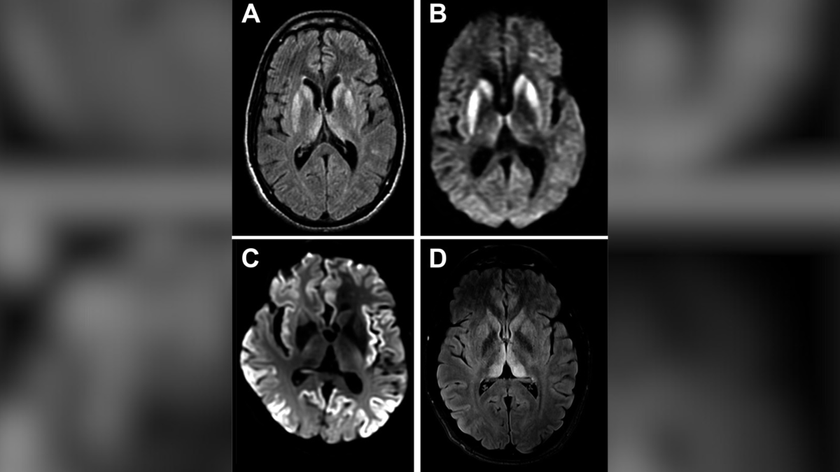

The researchers took samples of the tissue every two to three days, and examined it using a variety of methods: the naked eye, a microscope, DNA analysis, and X-ray imaging methods.

Ancient process revealed

For the most part, the mummification was successful, but it took nearly seven months (208 days), which is much longer than the two months the ancient Egyptian method took, according to Herodotus. (Other accounts report that it took even less time.)

"We were not so quick like the ancient Egyptians," Papageorgopoulou said. She suspects the cooler, damper conditions in the lab in Zurich, compared with the arid environment of ancient Egypt, may explain the discrepancy.

The salt solution effectively removed the water from the leg tissue, which prevented bacteria and fungi from degrading it. The microscopic analysis revealed good preservation of the skin and muscle tissue, as well.

The results show just how effective the Egyptian embalming methods were, and offer a detailed view of how the process worked. "It's more or less state-of-the-art documentation on how the ancient Egyptians mummified their bodies," Papageorgopoulou said.

The study revealed that the environment's temperature, acidity and humidity were all crucial factors in the speed of the mummification process. The experiment also showed how the removal of water from the tissues using salts prevented the body from degrading. Overall, the mummification process preserved the muscle and skin tissue very well, the researchers said.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Most Popular