This is the Dinosaur That Tested Life's Size Limits (Video)

Rachel Ewing is a news officer for science and health at Drexel University. She contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

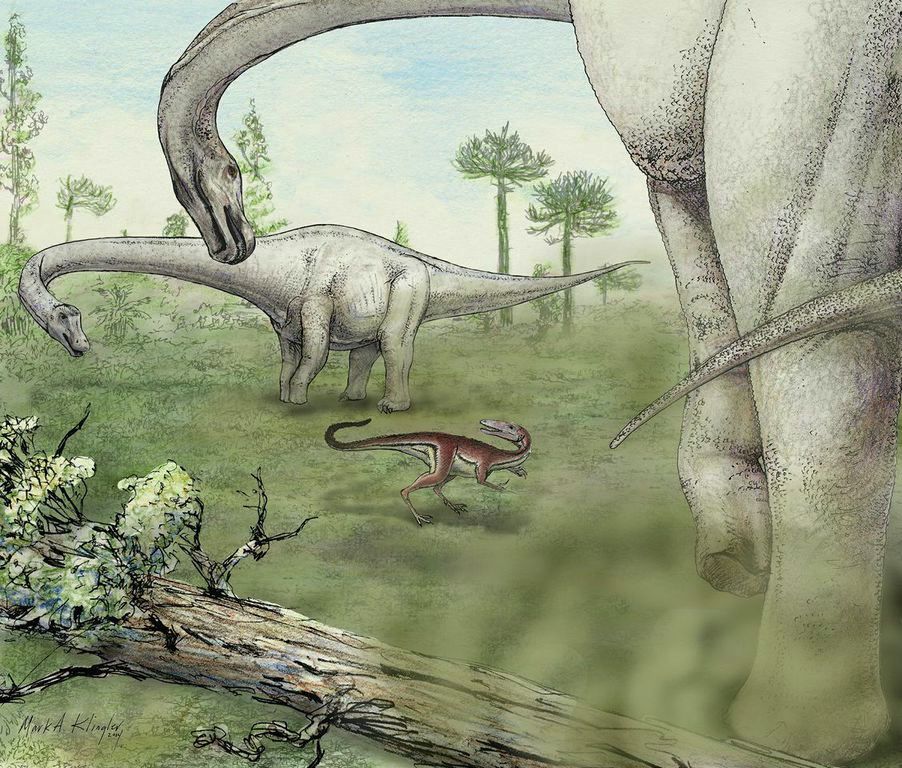

Scientists have a lot of unanswered questions about how the biggest dinosaurs that ever lived managed to move their enormous bodies on land. With the discovery of the supermassive dinosaur Dreadnoughtus schrani, the most complete skeleton ever found of its type, paleontologists have an unprecedented window into the anatomy and biomechanics of the largest animals to ever walk the Earth.

"Dreadnoughtus schrani was astoundingly huge," said Kenneth Lacovara, a professor of paleontology and geology at Drexel University. He discovered the Dreadnoughtus fossil skeleton in southern Patagonia in Argentina and led the excavation and analysis. His team published the discovery in the journal Scientific Reports in September 2014.

Dreadnoughtus schrani is the largest land animal for which scientists have accurately calculated a body mass: 59,300 kilograms (65 tons) and 26 meters (85 feet) long.

The completeness of its skeleton, with over 70 percent of the bones represented (although unfortunately, not the head) — is exceptional among the world's most super-massive dinosaurs. Over 100 elements of the Dreadnoughtus skeleton are present, including most of the vertebrae from the 30-foot-long tail, a neck vertebra with a diameter of more than 1 m (3 ft.), scapula, numerous ribs, toes, a claw, a small section of jaw and a single tooth, and nearly all the bones from both forelimbs and hind limbs (including a femur more than 2 m (6 ft.) tall) and a humerus.

To better visualize the skeletal structure of Dreadnoughtus, Lacovara's team digitally scanned all of the bones from both dinosaur specimens. They have made a "virtual mount" of the skeleton that is now publicly available for viewing in the paper's open-access online supplement as a 3D digital reconstruction.

The 3D laser scans of Dreadnoughtus show the deep, exquisitely preserved muscle attachment scars, providing a wealth of information about the function and force of the animal's muscles and where they attached to the skeleton — information that is lacking in many other sauropod dinosaurs. The bones themselves were returned to Argentina in late 2014, but with 3D digital reconstructions and 3D printing, research in Lacovara's lab and among his colleagues continues. Efforts to understand this dinosaur’s body structure, growth rate, and biomechanics are ongoing areas of research.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For more about the discovery, see Drexel University's Dreadnoughtus video.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.