Sacrificed Humans Discovered Among Prehistoric Tombs

A prehistoric cemetery containing hundreds of tombs, some of which held sacrificed humans, has been discovered near Mogou village in northwestern China.

The burials date back around 4,000 years, before writing was developed in the area. In just one archaeological field season — between August and November 2009 — almost 300 tombs were excavated, and hundreds more were found in other seasons conducted between 2008 and 2011.

The tombs were dug beneath the surface of the ground and were oriented toward the Northwest. Some of the tombs had small chambers where finely crafted pottery was placed near the deceased. Archaeologists also found that mounds of sediment covered some of the tombs, which could have marked the location of these tombs. [See Images of the Ancient Tombs and Artifacts in China]

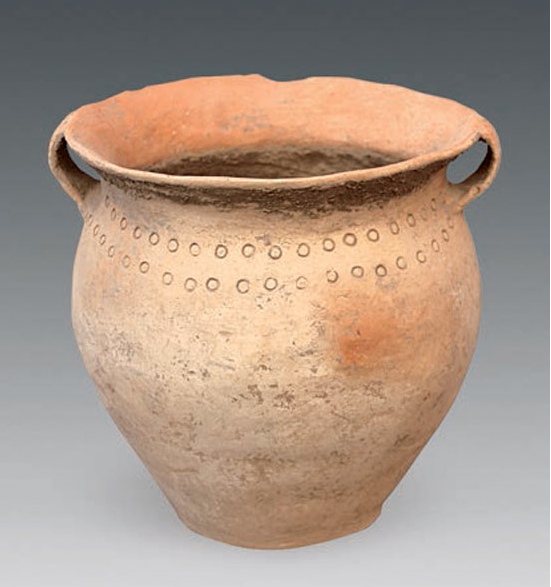

Within the tombs, archaeologists found entire families buried together, their heads also facing the Northwest. They were buried with a variety of goods, including, necklaces, weapons and decorated pottery.

Human sacrifices were also evident in the burials. In one tomb, "the human sacrifice was placed on its side with limbs bent and its face toward the tomb chamber. The bones are relatively well preserved, and the individual's age at death is estimated at around 13 years," archaeologists wrote in a paper published recently in the journal Chinese Cultural Relics.

Predicting the future

The goods found in the tombs included pottery decorated with incised designs. In some cases, the potter made numerous incisions shaped like the letter "O," with the O's forming patterns on the vessel. Sometimes, instead of making O's, the potter would incise wavy lines near the top of the pot.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers also discovered artifacts that could have been used as weapons. Bronze sabers were found that researchers say could have been used for cutting. They also found stone mace heads. (A mace is a blunt weapon that can smash a person's skull in.) Axes, daggers and knives were also found in the tombs.

Archaeologists also found what they call "bone divination lots," or artifacts that could have been used in rituals aimed at predicting the future. Bone divination was practiced widely throughout the ancient world. In fact, when writing was developed in China centuries later, some of the earliest texts were written on bones used for divination.

Qijia culture

Most of the tombs belong to the Qijia culture, whose people used artifacts with similar designs and lived in the upper Yellow River valley.

"Qijia culture sites are found in a broad area along all of the upper Yellow River as well as its tributaries, the Huangshui, Daxia, Wei, Tao and western Hanshui rivers," Chen Honghai, a professor at Northwestern University in China, wrote in a chapter of the book "A Companion to Chinese Archaeology" (Wiley, 2013).

Honghai wrote that people from the Qijia culture lived in a somewhat arid area. To adjust to these conditions, the Qijia people grew millet, a cereal suited to a dry environment; and raised a variety of animals, including pigs, sheep and goats.

People from the Qijia culture lived in modest settlements (smaller than 20 acres), in houses that were often partially buried beneath the ground. "Remains of buildings are mainly square or rectangular, and they are usually semi-subterranean. The doors usually point south, identical to the current local custom of building houses, as rooms on the sunny side receive more light and warmth," Honghai wrote.

Scientists aren't certain why the Qijia people engaged in human sacrifice or whom they sacrificed. They may have conquered other groups, enslaving and sacrificing them, Honghai said.

The team's report was initially published in Chinese in the journal Wenwu and focused on discoveries made between August and November 2009. Their report was translated into English and was published in the most recent edition of the journal Chinese Cultural Relics.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.