Charlie Charlie Challenge: Can You Really Summon a Demon?

"Charlie, Charlie, can we play?"

That is the seemingly innocent question that begins a new "spirit-summoning" game that is taking the Internet by storm. The so-called Charlie Charlie Challenge is based on shaky science (the objective is to summon a malignant spirit from beyond the grave), but there are some real and powerful forces behind this parlor game, according to one expert.

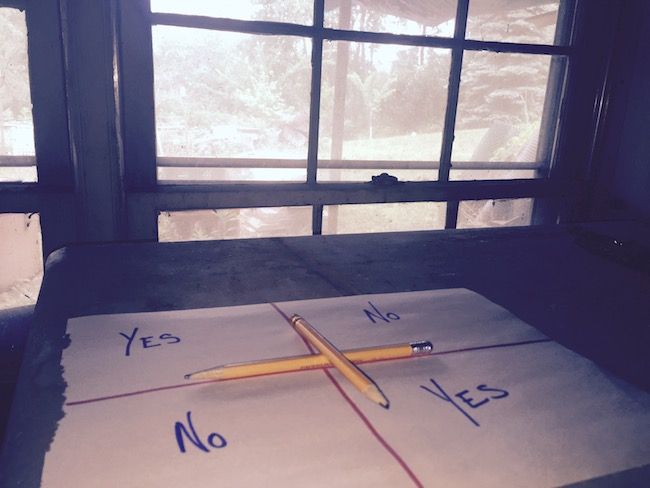

Here's how the Charlie Charlie Challenge works: players balance one horizontally aligned pencil on top of a vertically aligned pencil (essentially, in the shape of a cross). Both writing utensils sit atop a piece of paper divided into four quadrants. Two of the quadrants are labeled "yes" and two are labeled "no." Players then invite a spirit, Charlie, to play with them. If the spirit is feeling playful, the top most pencil will allegedly spin until it points to "yes." Then the players can ask Charlie other yes or no questions and wait for the pencil to move again. [The Surprising Origins of 9 Common Superstitions]

So what causes the pencils to spin of their own accord? Only one of the most powerful forces on Earth: gravity. In order to balance one object on top of another, the topmost object's center of gravity (a point where an object's mass is said to be concentrated) must be positioned precisely over the supporting object. In the case of the Charlie Charlie Challenge, players balance two long objects with rounded edges on top of one another. Naturally, these hard-to-balance objects have a tendency to roll around.

"Trying to balance one pencil upon another results in a very unstable system," said Christopher French, head of the anomalistic psychology research unit at the University of London in the United Kingdom. "Even the slightest [draft] or someone's breath will cause the top pencil to move."

And the precariously placed pencils will move around regardless of whether you summon a demon after balancing them, French told Live Science. This proves that there's no demonic force necessary for the pencil-moving effect to occur, he said.

Of course, pencils that move without anyone touching them might seem spooky in the right setting (i.e., in a candlelit room in the middle of the night), but as French pointed out, the situation is really no more threatening than a curtain blowing in the breeze.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Mind games

To be fair, gravity is not the only force at work in the Charlie Charlie Challenge. It's also possible that another formidable power, the power of suggestion, has a role to play.

A 2012 study published in the journal Current Directions in Psychological Science found that people often employ a "response expectancy" in certain situations. In other words, by anticipating that something will occur, a person's thoughts and behaviors will help bring that anticipated outcome to fruition. In the case of this spirit-summoning game, it could be that players expect a certain result and their actions during the game help bring it about (for instance, a well-timed breath or a subtle wave of the hand).

This hypothesis is similar to one suggested by French, who pointed out that many forms of recreational divination — like Ouija (the board game where you put your hands on a piece of plastic that allegedly moves of its own accord to answer your questions) or table turning (an old-school parlor game where people put their hands on a table and wait for the table to turn of its own volition) — involve the subconscious actions of participants. [Really? The World's Greatest Hoaxes]

The "magic" behind the Ouija board and turning tables, along with pendulums and dowsing rods (two other popular forms of divination), has been scientifically explained through something known as the "ideomotor effect," French said.

The ideometer effect was first described in the 19th century by the English doctor and physiologist William Carpenter. It suggests that it's the involuntarily muscular movements of the people using the plastic planchette in Ouija, or the people sitting around the table in table turning, that causes these objects to move. The ideometer effect doesn't completely explain the Charlie Charlie phenomenon, because players don't touch the pencils used in the game. However, the game is similar to these other examples because it involves what French calls "magical thinking," or the belief that a random event (the spinning of a pencil) is related to some unconnected, and in some cases imaginary, force or energy (a spirit).

"Often the 'answers' received [in divination games] might be vague and ambiguous, but our inherent ability to find meaning — even when it isn't there — ensures that we will perceive significance in those responses and be convinced that an intelligence of some kind lay behind them," French said.

The Charlie Charlie Challenge is magical thinking at its finest, according to French, who explained that this sort of thinking may have played an important role in human evolution. It made sense for our human ancestors to see "sentience and intention" in unexplained everyday events, he said, because these events may have represented real threats that needed to be avoided.

"The cost of avoiding a threat that wasn't really there was far less than that of missing a threat that was really there," French said.

This tendency to attribute a deeper meaning to meaningless or unrelated events persists in modern brains, French said. He added that this innate tendency could help explain why so many people believe that the random responses in the Charlie Charlie Challenge really are coming from an intelligence that is trying to send them a message.

Follow Elizabeth Palermo @techEpalermo. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Elizabeth is a former Live Science associate editor and current director of audience development at the Chamber of Commerce. She graduated with a bachelor of arts degree from George Washington University. Elizabeth has traveled throughout the Americas, studying political systems and indigenous cultures and teaching English to students of all ages.