A giant shark the size of a two-story building prowled the shallow seas 100 million years ago, new fossils reveal.

The massive fish, Leptostyrax macrorhiza, would have been one of the largest predators of its day, and may push back scientists' estimates of when such gigantic predatory sharks evolved, said study co-author Joseph Frederickson, a doctoral candidate in ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Oklahoma.

The ancient sea monster was discovered by accident. Frederickson, who was then an undergraduate at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, had started an amateur paleontology club to study novel fossil deposits. In 2009, the club took a trip to the Duck Creek Formation, just outside Fort Worth, Texas, which contains myriad marine invertebrate fossils, such as the extinct squidlike creatures known as ammonites. About 100 million years ago the area was part of a shallow sea known as the Western Interior Seaway that split North America in two and spanned from the Gulf of Mexico to the Arctic, Frederickson said.

While walking in the formation, Frederickson's then-girlfriend (now wife), University of Oklahoma anthropology doctoral candidate Janessa Doucette-Frederickson, tripped over a boulder and noticed a large vertebra sticking out of the ground. Eventually, the team dug out three large vertebrae, each about 4.5 inches (11.4 centimeters) in diameter. [See Images of Ancient Monsters of the Sea]

"You can hold one in your hand," but then nothing else will fit, Frederickson told Live Science.

The vertebrae had stacks of lines called lamellae around the outside, suggesting the bones once belonged to a broad scientific classification of sharks called lamniformes that includes sand tiger sharks, great white sharks, goblin sharks and others, Frederickson said.

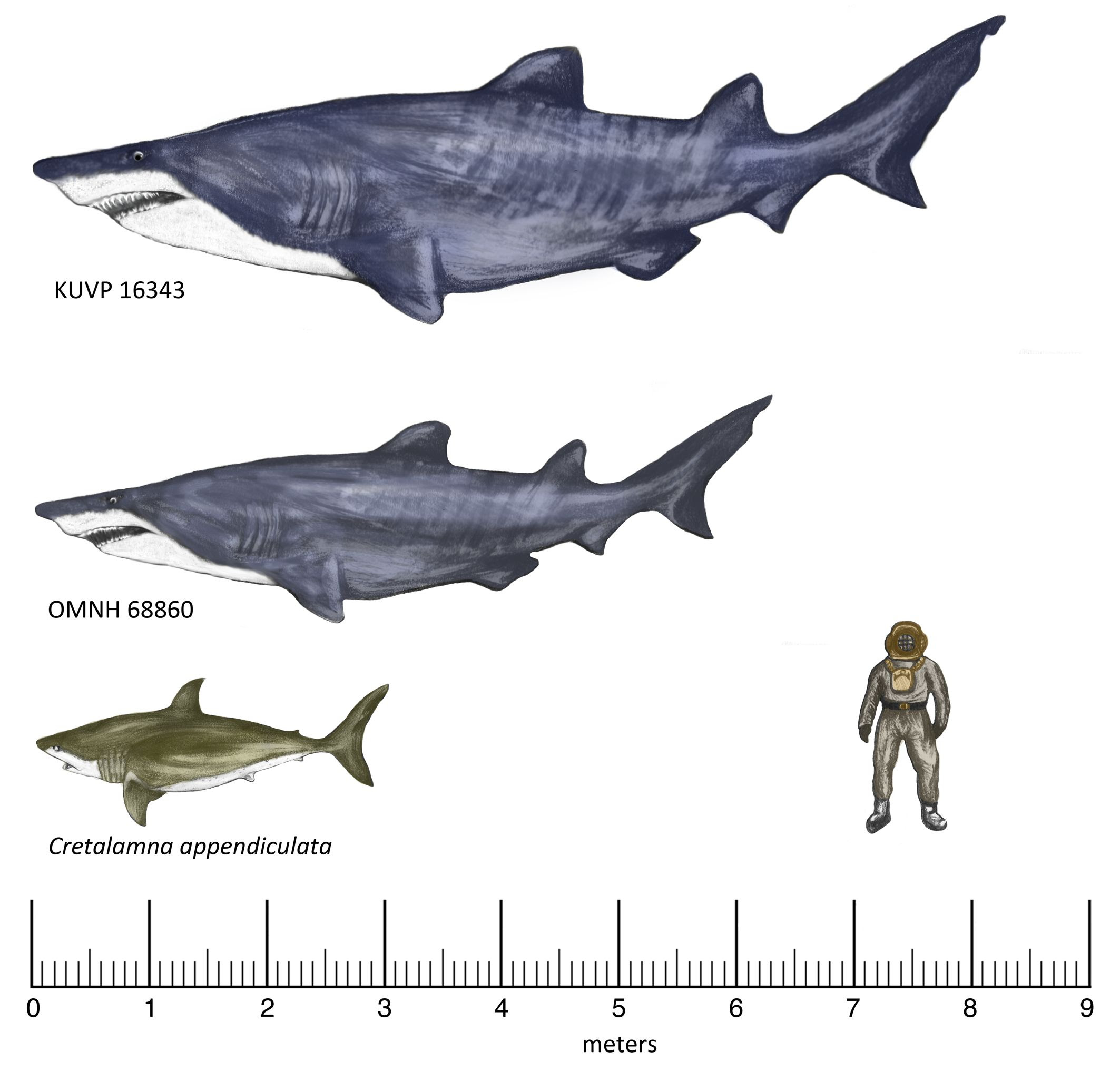

After poring over the literature, Frederickson found a description of a similar shark vertebra that was unearthed in 1997 in the Kiowa Shale in Kansas, which also dates to about 100 million years ago. That vertebra came from a shark that was up to 32 feet (9.8 meters) long.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

By comparing the new vertebra with the one from Kansas, the team concluded the Texas shark was likely the same species as the Kansas specimen. The Texan could have been at least 20.3 feet (6.2 m) long, though that is a conservative estimate, Frederickson said. (Still, the Texas shark would have been no match for the biggest shark that ever lived, the 60-foot-long, or 18 m, Megalodon.)

By analyzing similar ecosystems from the Mesozoic Era, the team concluded the sharks in both Texas and Kansas were probably Leptostyrax macrorhiza. Previously, the only fossils from Leptostyrax thatpaleontologists had found were teeth, making it hard to gauge the shark's true size. The new study, which was published today (June 3) in the journal PLOS ONE, suggests this creature was much bigger than previously thought, Frederickson said.

Still, it's not certain the new vertebrae belonged to Leptostyrax, said Kenshu Shimada, a paleobiologist at DePaul University in Chicago, who unearthed the 1997 shark vertebra.

"It is also entirely possible that they may belong to an extinct shark with very small teeth so far not recognized in the present fossil record," Shimada, who was not involved in the current study, told Live Science. "For example, some of the largest modern-day sharks are plankton-feeding forms with minute teeth, such as the whale shark, basking shark and megamouth shark."

Either way, the new finds change the picture of the Early Cretaceous seas.

Previously, researchers thought the only truly massive predators of the day were the fearsome pliosaurs, long-necked, long-snouted relatives to modern-day lizards that could grow to nearly 40 feet (12 m) in length. Now, it seems the oceans were teeming with enough life to support at least two top predators, Frederickson said.

As for the ancient shark's feeding habits, they might resemble those of modern great white sharks, who "eat whatever fits in their mouth," Frederickson said. If these ancient sea monsters were similar, they might have fed on large fish, baby pliosaurs, marine reptiles and even full-grown pliosaurs that they scavenged, Frederickson said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.