Bones with names: Long-dead bodies archaeologists have identified

Historians record biographies of the rich and famous: kings, queens, emperors and knights. Archaeologists, more often than not, dig up common people, who remain stubbornly anonymous in death.

Occasionally, however, the written record and the archaeological record collide. In rare situations, researchers are actually able to identify a collection of bones as a person in the historical record. Many of these identifiable, or "individualized," remains belonged to royalty or other high-profile people, the sort who tend to be buried in lavish graves stamped with their names.

The bodies of royalty are not necessarily more important to archaeologists, who can learn much about diet and lifestyle by examining the bones of commoners. But there's something thrilling about uncovering this concrete evidence of the past. Read on for seven skeletons that have regained their rightful names, and three more that are tantalizingly close.

1. Richard III

The last Plantagenet king of England set off an international fervor in 2013, when archaeologists announced the discovery of his bones under a parking lot in Leicester. The king, who died in 1485 at the Battle of Bosworth Field, had been scrunched into a hastily dug grave. Researchers identified him by his battle wounds, which matched those the king was reported to have sustained during and after his death, and by his DNA, thanks to a pair of living descendants via his sister's line.

After the analysis of his remains, Richard III finally got a royal burial at Leicester Cathedral on March 26, 2015 — 530 years after his death.

2. King Tut

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The older a skeleton, the less likely historical records survive to identify it. Fortunately, the ancient Egyptians and their carefully prepared mummies provide an exception to this rule. Although the boy king Tutankhamun died in approximately 1323 B.C., his identification was in no doubt after Howard Carter and George Herbert discovered his gold-laden tomb in 1922.

Tut's mummy revealed him to be a slight young man with a clubfoot. Having a positive ID on the young king is enabling researchers to tie together the dynastic family tree using DNA. In 2010, researchers announced they'd identified mummies belonging to Tutankhamun's father, mother and grandmother.

3. Queen Eadgyth

In 2008, German archaeologists opened a tomb in the Magdeburg Cathedral, expecting it to be empty. To their surprise, they found a lead sarcophagus inscribed with the words "EDIT REGINE CINERES HIC SARCOPHGVS HABET." This translates to: "The remains of Queen Eadgyth are in this sarcophagus."

Slam dunk identification, right? Not so fast. Archaeologists knew that the bones of the Saxon queen Eadgyth, who died in 946 A.D., had been moved at least three times. They could have easily been lost and replaced.

So scientists set to analyzing the bones. They extracted isotopes, variations of certain molecules, from the skeleton's teeth. Isotopes are integrated into the body through the diet, so they can pinpoint what an individual ate during their lives.

The tooth isotopes pointed to a childhood in Wessex, England, matching the historical record of Queen Eadgyth. She also ate a high-protein diet and her skeleton bore signs of horseback riding, the archaeologists discovered, befitting her royal status.

4. Xin Zhui

One of the best-preserved bodies ever discovered by archaeologists belonged to Xin Zhui, also known as Lady Dai. Xin Zhui was the wife of the Marquis of Dai during the third century B.C., and when she died around the age of 50 in what is now Hunan, China, she was buried in style. Her tomb was full of her belongings, including cosmetic boxes, musical instruments, painted silk and tablets about health and medicine.

Tucked away in four nested pine boxes, Xin Zhui was so well-preserved upon her discovery in the 1970s that her skin was still moist and her limbs pliable. Her body is now kept in a preserved state at the Hunan Provincial Museum.

5. Ramesses I

The tomb of the first ruler of Egypt's 19th dynasty, Ramesses I, was discovered in 1817. Unfortunately, Ramesses I wasn't in it.

Years later, in 1881, a family of Egyptian goat-herders-turned-tomb-robbers revealed to archaeologists where they'd been getting the items they'd been selling on the black market for years: a cliff-side tomb above Deir el-Bahri, a mortuary complex across the Nile from the city of Luxor.

The tomb acted as a cache for royal mummies removed during the looting of tombs elsewhere, according to the Michael C. Carlos Museum at Emory University. Inside was a coffin inscribed with the name of Ramesses I — but inside that was nothing but loose bandages. So where was Ramesses? [In Photos: The Mummy of King Ramesses III]

Canada, as it turned out. Yes, the founder of Egypt's 19th dynasty and grandfather of the famed Ramesses the Great was acting as a sideshow exhibit for tourists at the Niagara Falls Museum and Daredevil Hall of Fame. At the time, purchasing mummies from Egypt was as easy as walking down the right alley to find a street merchant selling looted tomb goods. The body of Ramesses I ended up in this trade. When the Niagara Falls Museum sold off its collections in 1999, Emory raised the money to purchase the suspected Ramesses I mummy in less than two weeks. Researchers there used computed tomography (CT) scans, facial reconstructions and detailed study of the mummification techniques to confirm that the roaming mummy was indeed the lost pharaoh. (The mummy was returned to Egypt in 2003.)

6. Ramesses III

Historical records, penned on papyrus, told of a palace plot to murder Ramesses III, but no one knew if that plot had succeeded. A CT scan of the pharaoh's mummy suggested that it did: Ramesses III's throat had been slit. The cut would have severed the trachea, esophagus and major blood vessels to the head, killing him quickly, the researchers reported in the British Medical Journal.

During his mummification, priests placed a healing amulet in the neck wound and bound it tightly with bandages.

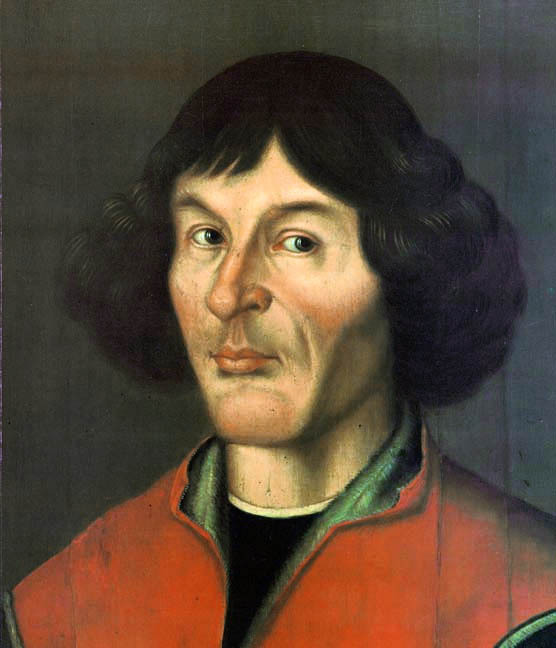

7. Copernicus

The first astronomer to realize that the Earth revolves around the sun, not the other way around, was buried in an unmarked grave in a Polish cathedral in 1543. But in 2009, Swedish and Polish researchers announced in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that they'd positively identified the remains of Nicolaus Copernicus.

The identification took some doing. First, researchers created a facial reconstruction of a skull of a man of the proper age found under the church floor in 2005. The results were promising — a mug that looked quite similar to contemporary paintings of Copernicus.

Next, the researchers turned to a few shed hairs found stuck in the bindings of a calendar owned by Copernicus. DNA testing revealed that two of the hairs matched the suspected Copernicus bones.

8. A Viking king?

Not everyone in history is considerate enough to leave DNA-bearing hair behind. In most cases, researchers have to take their best guess at an identification.

One such case is the discovery of a young man's skeleton buried near Auldhame in Scotland. The skeleton, which dated back to the 10th century, was found surrounded by expensive goods, including a Viking belt. This suggests that he was a high-status individual — perhaps even the Viking King Olaf Guthfrithsson himself.

King Olaf died in A.D. 941. Shortly before his death, the king attacked Auldhame and the nearby hamlet of Tyninghame. The location of the grave, combined with the goods inside it, suggests that skeleton could be Olaf himself. Unfortunately, archaeologists said, the evidence is only circumstantial, and with no living relatives for DNA comparison, the identification will remain speculative.

9. An unknown soldier?

After the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, the mass graves of fallen soldiers were raided for bones, which were ground up and used to fertilize fields in what is now Belgium. As a result, few full skeletons from the battle have been found.

But in 2012, a construction crew discovered the complete skeleton of a Waterloo casualty. The musket ball that killed the man was still lodged in his ribcage. Nearby were 20 coins, a spoon and a piece of wood engraved "CB," according to The Independent.

It wasn't enough to identify the man. That is, until archaeologists noticed the traces of an "F" before the "CB" and a military historian named Gareth Glover took up the case. By cross-referencing records of German soldiers who fought in the battle, Glover was able to determine that only one German with those initials had died: a 23 year-old named Friedrich Brandt.

As of June 2015, the body identified as Brandt was on display at the Lion's Mound Museum & Visitor Centre in Belgium.

10. Which Philip?

But which relatives? The debate boils down to two camps: those who believe the male tomb occupant to be Philip II, the father of Alexander who set the stage for his son's unprecedented conquests, and those who believe the skeleton belongs to Philip III Arrhidaios, Alexander's less-illustrious half-brother who ruled as a figurehead briefly after Alexander's death. (The female skeleton is presumed to be the wife, or one of the wives, of these men.)

Examinations of the bones have yet to yield any firm proof either way. Archaeologists argue over whether the bodies were cremated right after death, or later — Philip III was buried for more than a year before being exhumed for a royal cremation and funeral. They also bicker over whether the bones show signs of Philip II's known battle wounds. Ultimately, the bodies may not even provide the final clues, said Maria Liston, an anthropologist at the University of Waterloo who studies cremated remains.

"It's going to have to be, in the end, based a little bit at looking at the bones, but honestly on the dates of the pottery [in the tomb] and things like that," Liston told Live Science.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.