Mystery on Mercury: Strange Pattern of Huge Cliffs Defy Explanation

A baffling new mystery has turned up on Mercury — a pattern of giant cliffs and ridges on the planet's surface that defies any explanation that scientists have currently been able to offer.

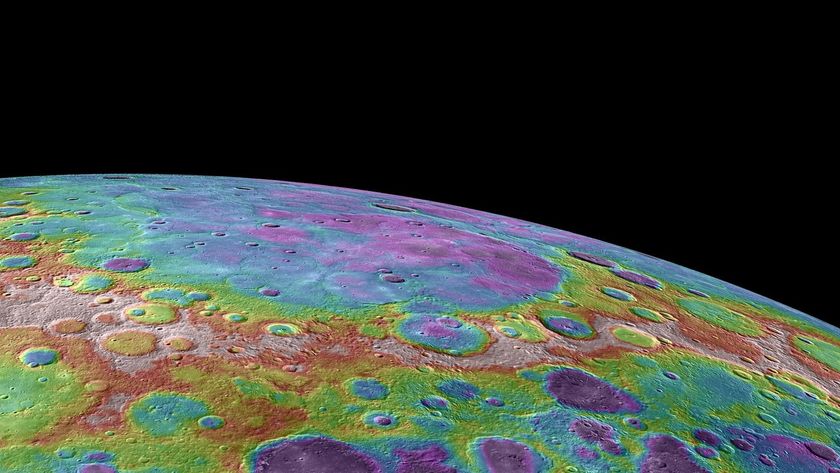

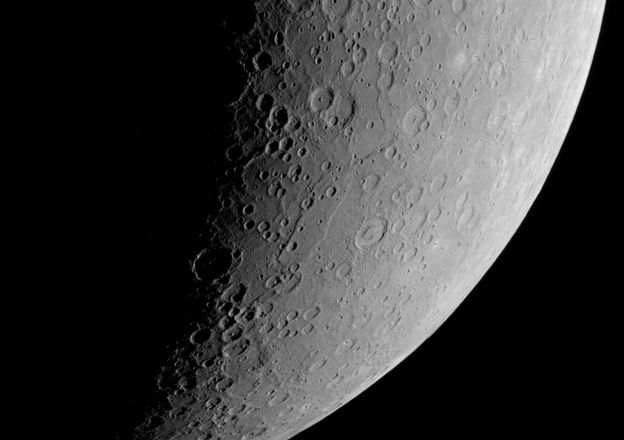

Mercury is the solar system's smallest and innermost world. It was an enigmatic planet for years. Until NASA's MESSENGER spacecraft became the first probe to orbit Mercury, the only other visits it received were the flybys made by NASA's Mariner 10 probe four decades ago. MESSENGER ended its mission in April by crashing into Mercury's surface.

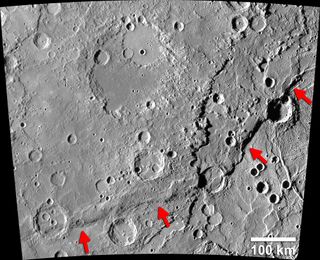

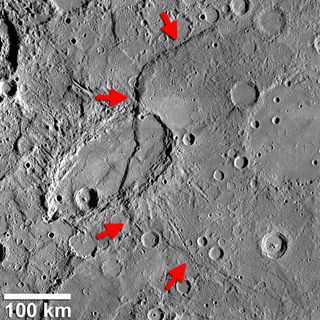

Images that MESSENGER collected during its more than four years in orbit revealed a vast array of large fault scarps, or cliffs, on Mercury. These scarps resemble giant stair steps in the landscape — the largest are more than 600 miles (1,000 kilometers) long and more than 1.8 miles (3 km) high. [See Mercury Photos by NASA's MESSENGER Probe]

These fault scarps form when rocks are pushed together, break and thrust upward along faults — or fractures — in the planet's crust. The most widely accepted model of the origin of these faults and scarps is that they are essentially wrinkles that formed on Mercury's surface as the planet's heart cooled over time, leading Mercury to shrink in size. Prior research has suggested that Mercury may have contracted by about 2.5 to 8.7 miles (4 to 14 km) in diameter.

If this planetwide array of fault scarps formed as Mercury shrank in size, these features should be uniformly scattered over the planet's surface. However, scientists now find there is a bewildering pattern to these fault scarps.

"It is a real mystery," study lead author Thomas Watters, a planetary scientist at the Smithsonian Institution's National Air and Space Museum, told Space.com.

The scientists analyzed the largest, most prominent fault scarps on Mercury's surface, which were more than about 30 miles (50 km) long. Unexpectedly, they discovered many scarps are concentrated in two wide bands that run north to south and are located on almost opposite sides of the planet from each other.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

One potential explanation for these bands might lie in the flow of hot rock in Mercury's mantle layer. "However, the scale of flow in Mercury's mantle is too small to explain these bands, because Mercury's mantle is not very thick — only 400 kilometers (250 miles) or so, we think," Watters said. "There must be other factors at play here we don't really have a grasp on yet."

In addition, about twice as many of Mercury's large fault scarps are located in its southern hemisphere than in its northern hemisphere. Of the 407 fault scarps that were more than about 30 miles (50 km) long that the researchers analyzed, 264 are in the south, adding up to about 20,500 miles (33,000 km), while 143 are in the north, for a total of about 8,700 miles (14,000 km).

"None of the models we have at present can account for the lopsided number of scarps between the hemispheres," Watters said. "We still have a lot to learn about Mercury."

The researchers will continue to analyze images and data from MESSENGER to shed light on this mystery. In addition, Watters noted that the BepiColombo spacecraft, set to launch in 2017, "may be able to give us a better picture of the global structure of the crust of Mercury." The BepiColumbo spacecraft is a joint mission of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA).

While Earth's surface is made up of multiple tectonic plates, Mercury only has one. "Mercury is ideal for investigating how one-plate planets evolve," Watters said. "Understanding Mercury is essential to explaining how planets may evolve elsewhere in the galaxy."

The scientists detailed their findings online May 29 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.