Photos: Rare Inscription from King David's Time

A rare inscription on a ceramic jar dates back to the time of King David, in the 10th century B.C., according to archaeologists with the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA). The inscription, found on a 3,000-year-old ceramic jar, reads "Eshba'al Ben Bada'" and is only the fourth inscription unearthed to date from the time of King David. [Read full story about the rare inscription]

Ancient Canaanite

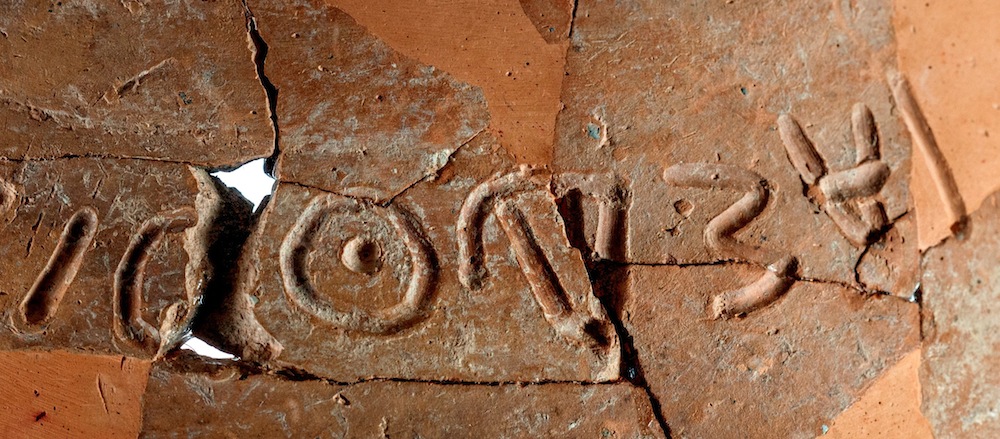

The letters in the inscription are written in ancient Canaanite script. This is the first discovery of the name Eshba'al on an ancient inscription in the country, according to the Israel Antiquities Authority. Eshba'al Ben Shaul ruled over Israel at the same time as King David. The name Eshba'al also appears in the Bible as a man who was murdered and decapitated by assassins who then sent his head to David in Hebron, the story goes. (Credit: Tal Rogovsky)

Canaanite letters

Here, a close-up of the inscription, revealing the letters (from right to left): aleph, shin, bet, 'ayin, lamed. The researchers led by archaeologists Yosef Garfinkel and Saar Ganor discovered the jar, shattered into hundreds of pieces, in 2012 during excavations at the biblical site Khirbet Qeiyafa— about 19 miles (30 kilometers) southwest of Jerusalem. They became curious about the jar when they noticed inscribed letters written in ancient Canaanite. (Credit: Tal Rogovsky)

Restored jar

The 3,000-year-old jar was was restored by researchers at the Israel Antiquities Authority. The fact that the name was inscribed on jars suggests Eshba'al was an important person, possibly the owner of an agricultural estate. There, the researchers suggest produce was packed and transported in ceramic jars inscribed with "Eshba'al." "This is clear evidence of social stratification and the creation of an established economic class that occurred at the time of the formation of the Kingdom of Judah," according to a statement by the IAA. (Credit: Tal Rogovsky)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Khirbet Qeiyafa

A view overlooking the ancient city at Khirbet Qeiyafa. Other ruins uncovered by archaeologists led by Garfinkel and Ganor include: a fortified city dating to the time of King David and overlooking the Valley of Elah, two gates, a palace and storeroom, and other dwellings. (Credit: Skyview Company, courtesy of the Hebrew University and the Israel Antiquities Authority)

Earliest Hebrew writing

Archaeologists discovered the earliest known Hebrew writing, a 10th century B.C. inscription, at the same site. The finding could mean the Hebrew Bible was written centuries earlier than scientists thought. Scholars have pinned the writing of the Hebrew Bible to the sixth century B.C. (Photo Credit: University of Haifa)

This ancient text puts the origin four centuries earlier than that. The ancient inscription reads (in English):

1' you shall not do [it], but worship the [Lord]. 2' Judge the sla[ve] and the wid[ow] / Judge the orph[an] 3' [and] the stranger. [Pl]ead for the infant / plead for the po[or and] 4' the widow. Rehabilitate [the poor] at the hands of the king. 5' Protect the po[or and] the slave / [supp]ort the stranger.

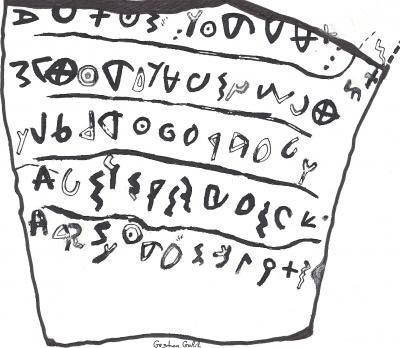

Earliest alphabetical text

An inscription on a jar fragment dating to the time of King David and King Solomon (10th century B.C.) is considered the earliest alphabetical text ever discovered in Jerusalem. Hebrew University archaeologist Dr. Eilat Mazar unearthed the jar fragment from beneath the second floor of an ancient building near the southern wall Jerusalem's Temple Mount.

Written in the Canaanite language, the text contains a combination of letters, which from left to right translate to m, q, p, h, n, (possibly) l and n. The archaeologists suspect the inscription could specify the jar's contents or the name of its owner. The text predates the earliest Hebrew inscription by about 250 years, the researchers said. (Photo Credit: Photo courtesy of Dr. Eilat Mazar; photographed by Ouria Tadmor)

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.