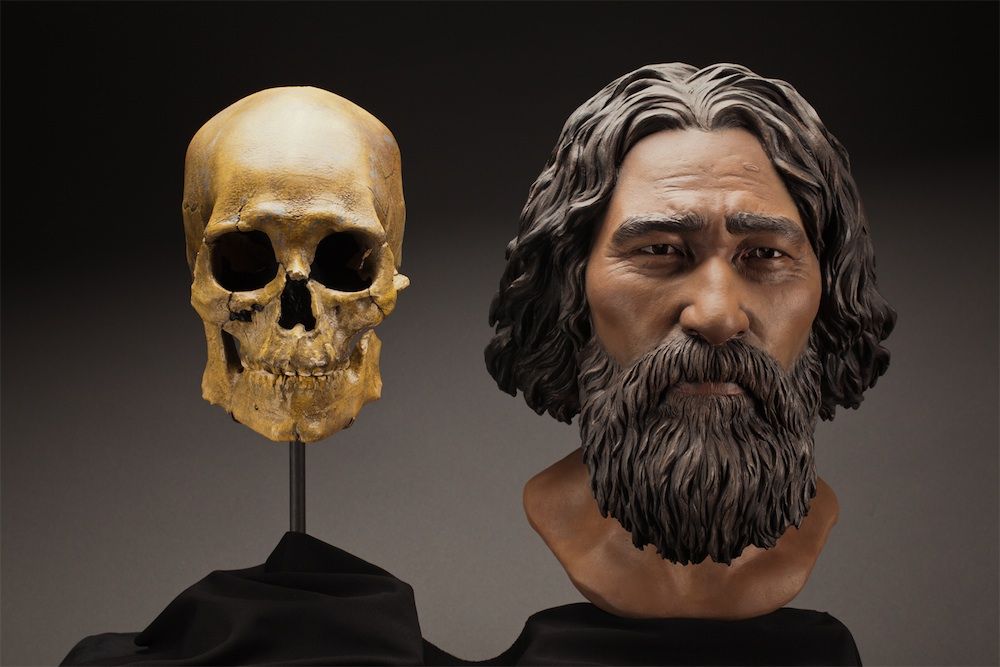

The relatives of a much-debated 8,500-year-old skeleton found in Kennewick, Washington, have been pinned down: The middle-age man was most closely related to modern-day Native Americans, DNA from his hand reveals.

The new analysis lays to rest wilder theories about the ancestry of the ancient American, dubbed Kennewick Man, said study co-author Eske Willerslev, an evolutionary biologist at the Natural History Museum of Denmark at the University of Copenhagen.

"There have been different theories, different mythology, everything from him being related to Polynesians, to Europeans, to [indigenous people] from Japan," Willerslev told Live Science. "He is most closely related to contemporary Native Americans." [In Photos: Human Skeleton Sheds Light on First Americans]

Disputed identity

A couple first discovered the skeleton in 1996 on the banks of the Columbia River in Kennewick. The coroner analyzing the remains noticed an arrow tip lodged in the man's pelvis, and surmised he was a European felled by a Native American, said co-author David Meltzer, an anthropologist at Southern Methodist University in Dallas.

But the man's bones revealed he was at least 8,000 years old.

At a news conference then, researchers studying the skeleton said the ancient man was "Caucasoid," an archaic, 19th-century term that includes a wide swath of people with origins in Africa, Western Asia and Europe. Reporters heard the word "Caucasian," and all of a sudden people were wondering how a European showed up in North America and was shot thousands of years before Europeans set foot on the continent, Meltzer said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"That was the moment when all the wheels fell off and this became quite the mess," Meltzer told Live Science.

Meanwhile, five Native American tribes argued the Kennewick Man was an ancestor, and since native graves are protected under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), the prehistoric man should be reburied on their land, not studied. A judge, however, concluded the Kennewick Man's Native American ancestry was in doubt, opening the door to more scientific research.

Rough life

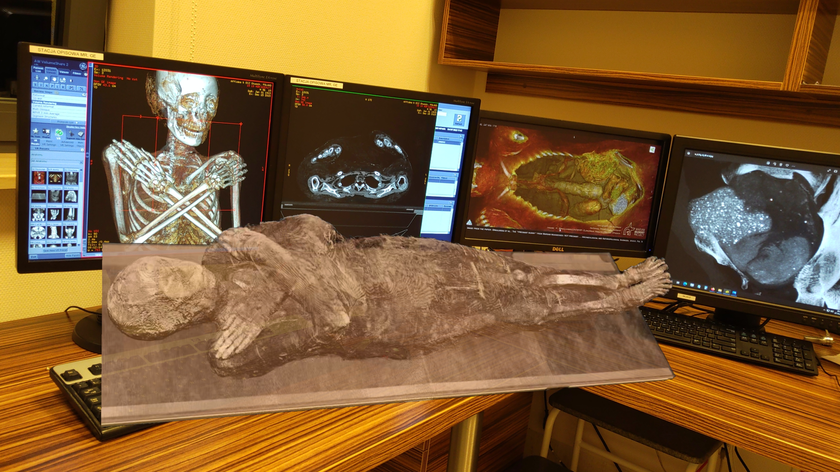

The first efforts to analyze the man's DNA failed, so researchers tried recreate some of the ancient man's life. It turned out he was between 35 and 45 years old, with developed muscles as well as rib fractures and other injuries suggesting a life of hard work. Chemical analysis of his bones suggested he ate a diet of mostly fish.

Most surprisingly, anthropologists measured his skull and concluded its shape tied him more closely to the modern-day Polynesians or the indigenous Ainu people of Japan than to modern-day Native Americans.

Native American Ancestry

In the new study, which was published today (June 18) in the journal Nature, Meltzer, Willerslev and their colleagues took a second look at DNA from a sliver of Kennewick Man's hand bone. They then compared that DNA with that of several modern-day Native American populations, as well as Ainu and Polynesian populations. The team also reanalyzed the skull and concluded that, because it was just one sample, it was well within the range of variation that could have been found among ancestral Native American populations. [Top 10 Mysteries of the First Humans]

"There's no getting around it, Kennewick Man is Native American," Meltzer said.

The team also found the closest genetic match came from people living along the Northwest coast, particularly the Colville people, who were some of the first to claim Kennewick Man as one of their own. But because not all the tribes that claim the Kennewick Man as an ancestor submitted DNA, and few other Native Americans have submitted DNA samples, other tribes could be even more closely related to him, Meltzer added.

If the Kennewick Man did come from the ancestral population of the Colville tribes, that would mean the same people have occupied roughly the same region for thousands of years, Willerslev said. The Colville tribes were historically a nomadic tribe that migrated between different hotspots for fishing and gathering berries, but they have long lived around the Columbia River, according to their website.

The new DNA also sheds light on the ancient migrations that peopled the Americas. Last year, Willerslev and his colleagues analyzed the DNA from a 12,600-year-old skeleton, known as the Anzick boy, unearthed in Montana. That DNA revealed the first Americans split into two groups before the Anzick boy lived. One lineage migrated southward to populate Central and South America, while another branch headed north along the northwest coast of North America and into Canada. The new data suggest Kennewick Man's group formed a third offshoot that diverged from the southern lineage, but migrated back north. This lineage includes modern Native Americans such as the Colville and some other Pacific Northwest tribes.

Still, with so few ancient American remains available for study, scientists can't completely recreate the history of these long-lost migrations, said Benjamin Auerbach, a professor of anthropology at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, who was not involved in the current study.

"As exceptional and important a study as this is, and as much as it reveals about early populations and ancestry in North America, Kennewick Man is only one individual," Auerbach told Live Science in an email. "Only through aggregating more information from these earliest human remains globally will we be able to shed light on broad patterns of human ancestry and migration."

Despite the new findings, it may be a while before Kennewick Man is finally laid to rest.

"This is just the first step in the process," Jim Boyd, chairman of the Colville Business Council and a spokesman for the tribe, said in an email. Now that the Native American DNA ancestry question is settled, "this will begin the NAGPRA process that will logically lead to joint repatriation and reburial," he said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.