Ancient, Shell-Less Turtle Sported Whiplike Tail

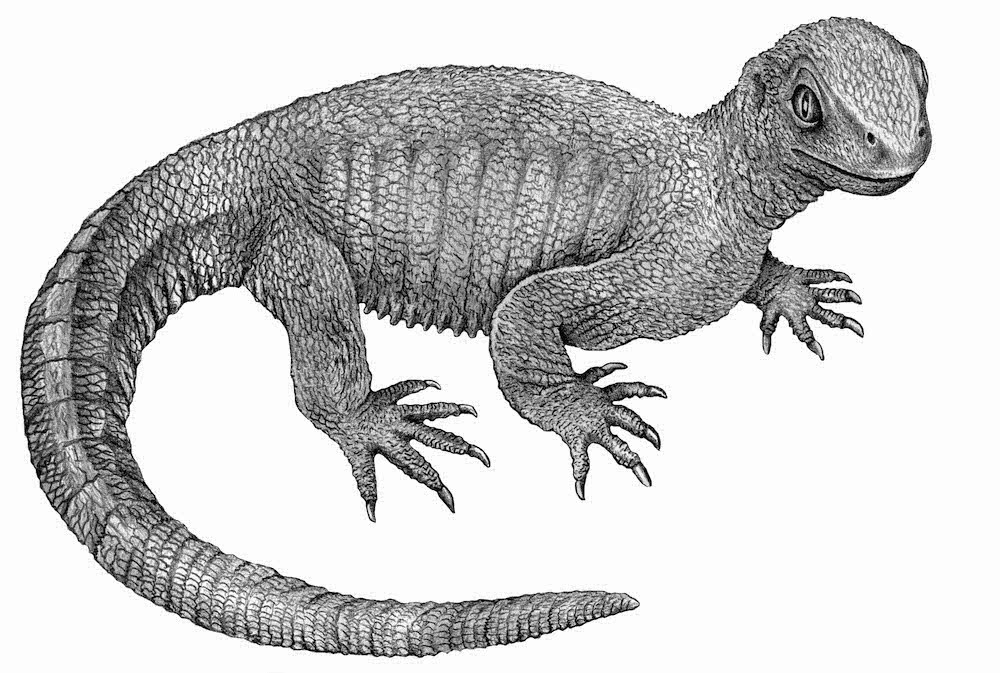

An ancestor of modern-day turtles, a shell-less creature with a long tail once puttered around an ancient lake, likely munching on insects and worms with its peglike teeth, a new study finds.

Researchers found the first fossils of the 240-million-year-old creature in 2006, during an excavation of Vellberg Lake, an ancient lakebed in southeastern Germany, said study researcher Hans Sues, a curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C.

"We now have well over a dozen specimens, including partial skeletons but also some isolated parts of skeletons," Sues told Live Science. "But we have a nice spectrum of sizes, so you can sort of see how the animal grows and changes." [Image Gallery: Fossilized Turtles Caught in the Act]

The researchers named the new species Pappochelys rosinae, from the Greek words "pappos" meaning grandfather — as the species is thought to be the "grandfather" of shelled turtles — and "chelys," meaning turtle. The species name honors I. Rosin, who prepared key specimens of the new taxon, Sues said.

P. rosinae was small, measuring about 8 inches (20 centimeters) long, but it fills in an important evolutionary gap, the researchers said.

"It's a beautiful link between the earliest precursors that we know of turtles, this animal called Eunotosaurus from South Africa that lived about 260 million years ago, and then later turtles that had a fully developed shell," Sues said.

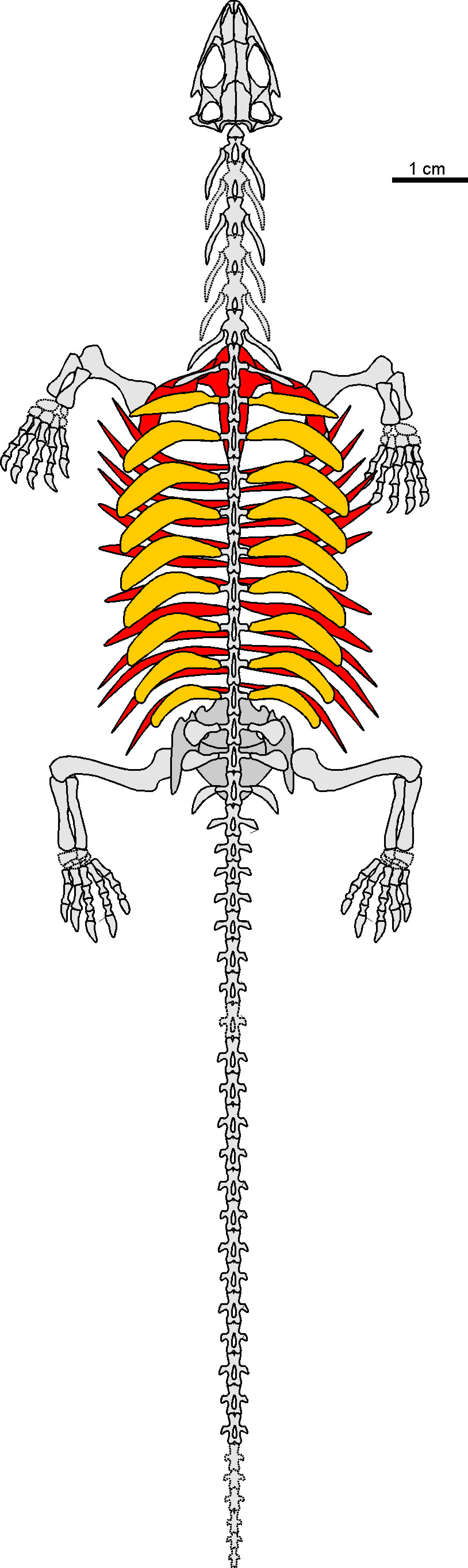

P. rosinae has broad trunk ribs, and belly armor made of thick, riblike structures. Coincidentally, researchers studying turtle evolution have hypothesized that turtle ancestors once had riblike structures such as these, as well as protective bones on the shoulder girdle, Hans said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Our new fossil beautifully confirms that," he said.

Turtle evolution

The P. rosinae fossils hold other clues about turtle evolution. The creature's skull has two small holes behind the eye sockets on either side, a feature seen in many reptiles today — though not modern turtles, making it difficult to understand the animal's evolutionary lineage.

Some scientists hypothesized that turtles had an ancient lineage and evolved from the base of the reptilian tree. In contrast, some molecular researchers suggested that turtles were more closely related to these so-called two-holed "diapsid" reptiles than to the earliest reptiles, which didn't have any openings at all, Sues said.

"This new fossil shows that the molecular people were actually right," he said. "It shows that turtles are closely related to other modern reptiles and didn't branch off early."

A reptilian tree analysis showed that turtles are more closely related to lepidosaurs, such as lizards and snakes, than they are to archosaurs, such as nonavian dinosaurs and birds, according to the study.

The researchers said they hope to paint a fuller picture of turtle evolution as more fossils emerge. The first fossil on record of a fully shelled turtle (Proganochelys) dates to between 205 million and 210 million years ago, Sues said. However, the creature couldn't withdraw its head and neck into its shell.

"What they did instead was they put armor on their head and neck to protect themselves," he said. [In Photos: Bones Reveal Ancient Sea Turtle]

Modern turtles, with the exception of sea turtles, can all withdraw their heads and necks into their shells in one of two ways: Most living turtles, such as tortoises, draw their necks back in an S-shape. However, a smaller group of turtles, such as the side-necked river turtle, draw their necks back sideways to hide them under the edge of their shells, Sues said.

The study was published online today (June 24) in the journal Nature.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.