Iron Age warrior lived with arrowhead in spine

It didn't immediately kill him.

A horrific spinal injury caused by a bronze arrowhead didn't immediately kill an Iron Age warrior, who survived long enough for his bone to heal around the metal point, a new study of his burial in central Kazakhstan finds.

"This found individual was extremely lucky to survive," said study researcher Svetlana Svyatko, a research fellow in the school of geography, archaeology and paleoecology at Queen's University Belfast in Northern Ireland. "It's hard to get a vertebral wound without damaging the main blood vessels, which would have resulted in an immediate death."

The male warrior was likely between 25 and 45 years old, and stood 5 foot 7 inches (174 centimeters) in height, which was tall considering that his people stood an average of 5 foot 4 inches (165 cm) in height, the researchers said. They found his grave, an elaborate burial mound called a "kurgan," after getting a tip from local people who live in the area.

Related: In photos: Boneyard of Iron Age warriors

Giant burial

The researchers have studied the area in central Kazakhstan for more than 20 years. Their work has shed light on the area's culture and the emergence of the powerful Scythians (also known as the Saka), a population of fierce nomads who lived on the central Eurasian steppes from about the eighth century B.C. to about the second century A.D., said study researcher Arman Beisenov, the head of prehistoric archaeology at the Institute of Archaeology in Kazakhstan.

During an excavation of a famous Saka cemetery in 2009 (a dig that yielded 200 jewellery pieces and more than 30,000 smaller ornaments, such as beads), locals told the researchers about a nearby kurgan that had been shamefully neglected and heavily devastated, Beisenov said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"What local people often want is attention and respect to their history and customs, which is the foundation of their present life and the key to the future," he told Live Science. "Although the schedule of our excavations was extremely tight and prohibitive for any extension, we anyway decided to follow the tip and take a look at the remains of the kurgan."

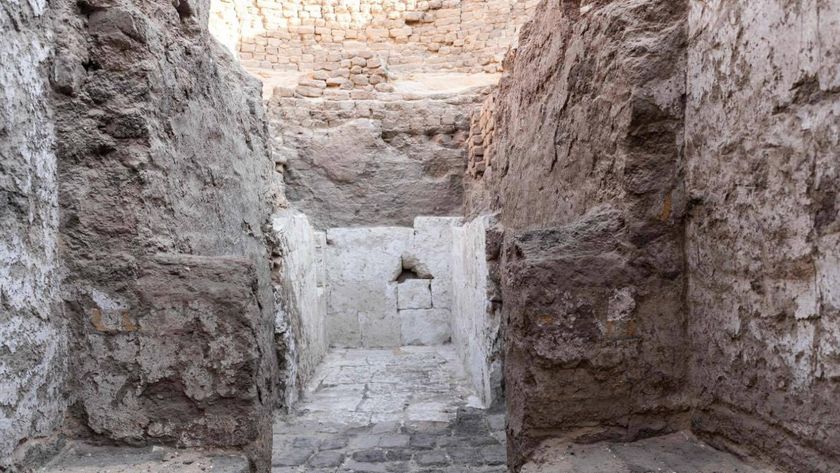

The kurgan was so magnificent that the researchers opened a new investigation, excavating the kurgan in 2010 and 2011. It was likely no more than 6.5 feet (2 meters) high and about 74 feet (22.5 m) in diameter when built, Beisenov said. However, evidence suggests that robbers plundered the site in ancient times, and that local people reused much of its soil and stones for housing in the 1960s and 1970s, he said.

Elite warrior

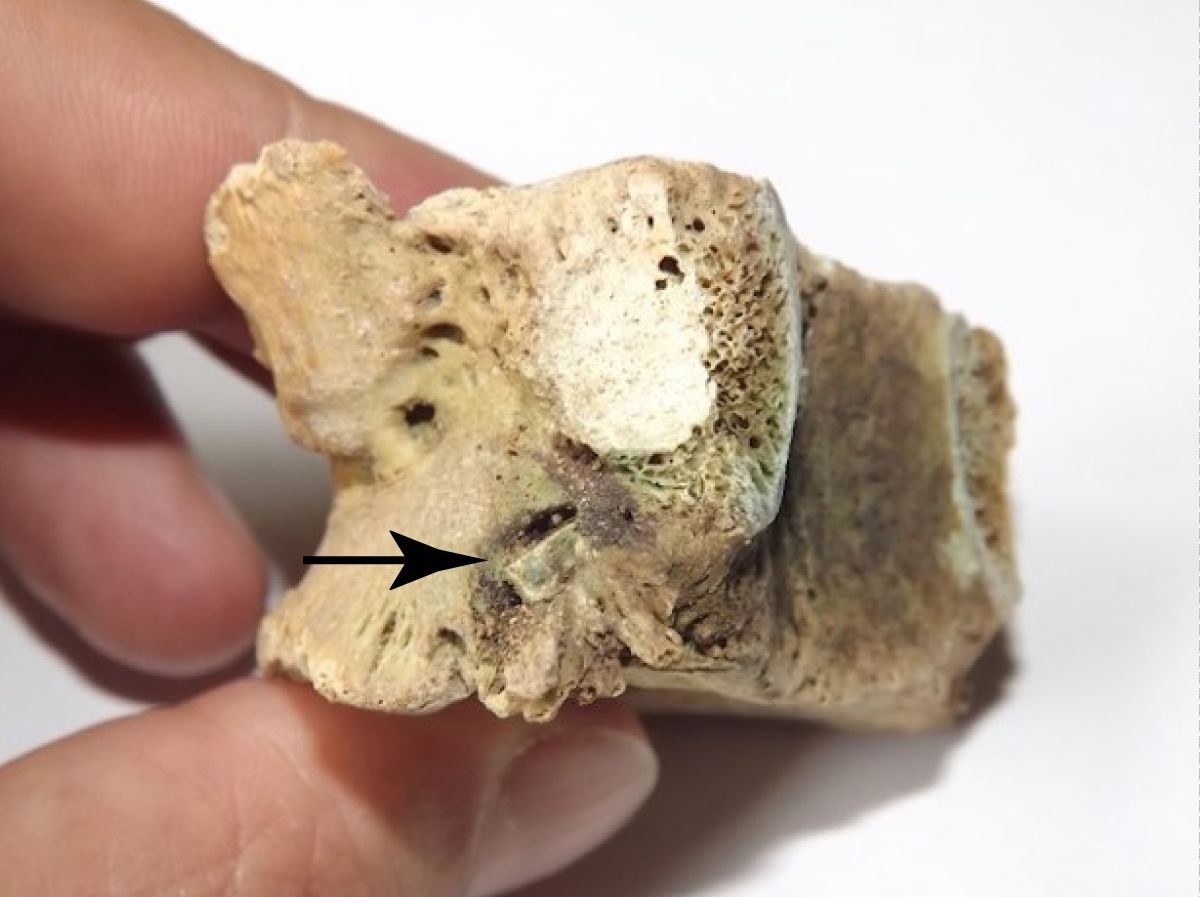

The grandiose grave suggests the individual belonged to the early Saka nomadic aristocracy, the researchers said. But the plundered kurgan held only a few scattered bones, including ribs, fibulae (lower-leg bones) and a vertebra. Radiocarbon dating suggests the individual lived sometime between the eighth and sixth centuries B.C., during the early Iron Age, according to the study.

A close look at the man's bones revealed a bronze arrowhead — made of copper, tin, and traces of lead and iron — lodged in one of his vertebra. The researchers also found a rib with a healed fracture, but it's unclear whether the man received these injuries at the same time as the arrow wound, the researchers said. It's also unclear how long he survived following his injuries, they said.

Computed tomography (CT) scans showed that the arrowhead, measuring 2.2 inches (5.6 cm) long, caused more than just a flesh wound. In fact, it "teaches us is the power of the human body to heal," said Aleksey Shitvov, a research team assistant at Queen's University Belfast who works with the group, but wasn't among the study's authors.

The scientists also looked at the chemical composition of the man's bones, and found he likely ate more millet (a type of grain) than did many of his Saka peers, Svyatko said.

"We can only speculate now what was the status of millet as a food for this society," Svyatko told Live Science. "Perhaps it was specifically accessible to high-ranked people or military elite, though this needs further investigation."

The study was published online June 22 in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.