Camel Spider's Fierce Jaw Is Focus of New Creepy Crawly 'Dictionary'

When you think of animals with large, powerful jaws, chances are you envision nature's fiercest predators — the great white shark, the grizzly bear. But one of the most ferocious jaws in the animal kingdom belongs to a creature that's quite a bit smaller than these huge beasts: the camel spider.

Ranging in size from tiny (just a few millimeters long) to eerily large (6 inches, or about 15 centimeters long), camel spiders inhabit desert regions all over the world. Despite the name, these critters aren't actually spiders; they're solifuges (belonging to the Solifugae order of arachnids), and these critters lack the silk and venom glands that would make them truly spiderlike. The camel spiders star in a new publication designed to help researchers better study the Solifugae order.

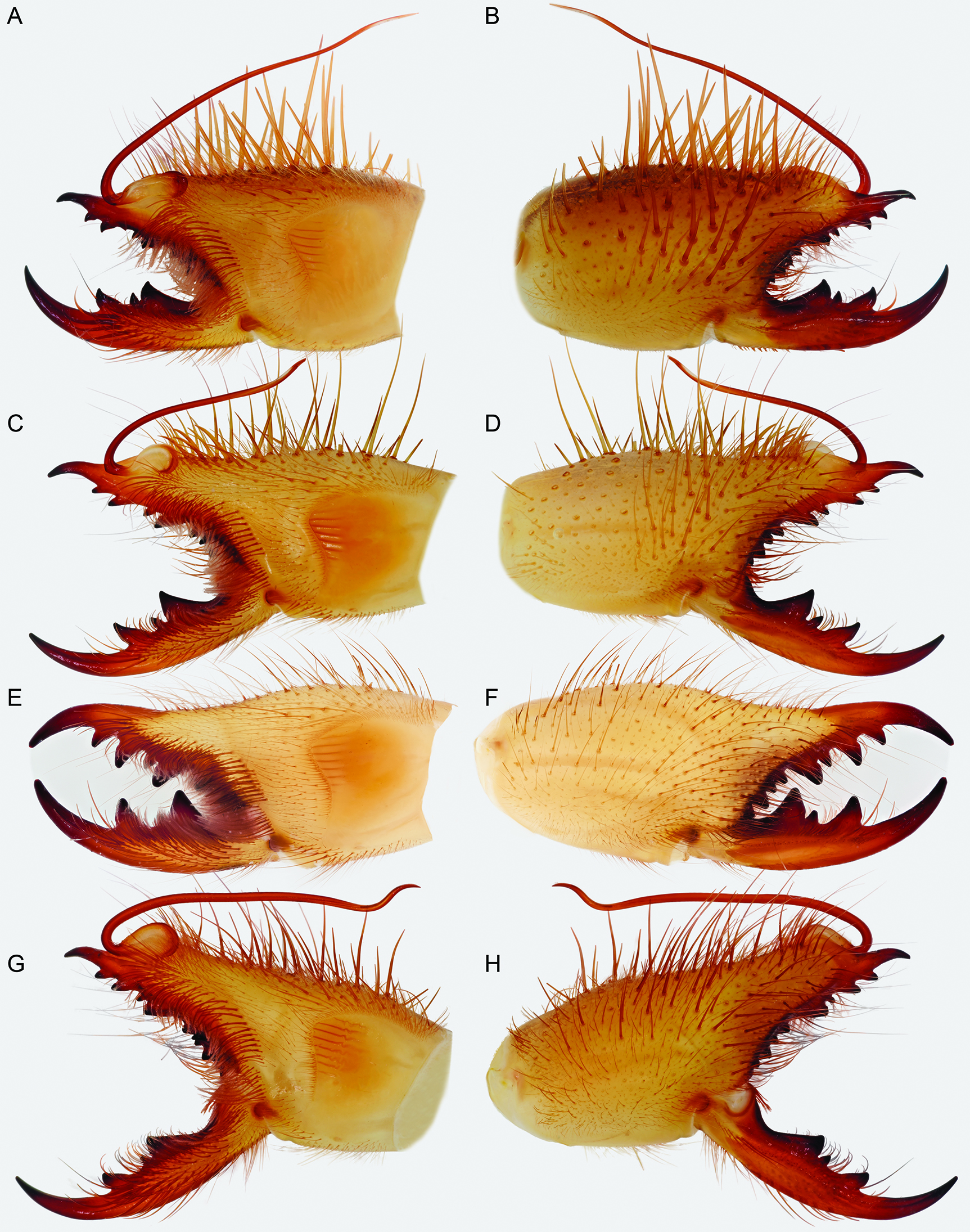

Of course, the camel spider's huge jaws, or chelicerae, also set it apart from its spider cousins. This critter boasts the largest jaw-to-body-size ratio of any animal in its subphylum, Chelicerata, which includes spiders, horseshoe crabs, sea spiders and scorpions. But, its giant chompers are good for more than just bragging rights (and munching on prey); they're also the body part that scientists rely on most to classify these animals. [In Photos: The Amazing Arachnids of the World]

The jaws of a solifuge contain "most of the relevant information" needed to tell one species of camel spider from the next, said Lorenzo Prendini, a curator in the Division of Invertebrate Zoology at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Prendini and several of his colleagues put together the new publication on solifuges, a dictionary-type collection of the creatures published last week in the Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History.

Filled with hundreds of close-up photos of this arachnid's oversize jaw (and teeth, and bizarre teeth hair), the new survey of solifuge morphology isn't exactly the kind of book you'd want to read before bed. But for Prendini and others who study camel spiders, it's an exciting development that solves a problem researchers face every day: getting people all over the world to talk about something using the same language.

"Different people have worked on the solifuges in their parts of the world and come up with their own little language for describing the species and communicating about them," Prendini told Live Science. One of the main objectives of the nearly 200-page survey was to create a standardized vocabulary for talking about camel spiders, he added.

The survey does away with the confusing language that once described the different structures found on a camel spider's jaws. No more "inside of" this and "left side of" that. Instead, the survey used terms like "prolateral" to describe the side of the jaw that faces the middle of the animal's body, and "retrolateral" to describe the side of the jaw facing away from this middle point.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Such terms are already common in scientific descriptions of other animals, particularly spiders, the researchers said. But unlike many species of spiders, solifuges aren't widely studied, and no one had previously gone to the trouble of homogenizing the language that researchers use to describe the arachnids, Prendini said. He said he hopes the new survey will encourage scientists to look at solifuges more closely now that researchers can describe the creatures with greater confidence.

The new paper brings together the most current data on things like solifuge mating behaviors and sound production (larger species of camel spiders rub their chelicerae together to make noise). But much remains to be learned about the animals' life cycle and reproductive habits, Prendini said. For example, the jawbones of male camel spiders appear to be smaller and more "graceful" than those of female camel spiders, but Prendini said he and his colleagues aren't sure why. [Animal Sex: 7 Tales of Naughty Acts in the Wild]

"There's some evidence that the males might not eat as much as the females when they reach sexual maturity. They may not eat at all," Prendini said. "They may only use their jaws in mating, but we don't have hard data to say whether that's the case."

The researchers said they hope that these small tidbits of information and the hypotheses they inspire will catch the eyes of those equipped to answer the bigger questions about camel spiders. Perhaps then, the world will find out more about these fascinating creatures, the researchers said.

"One of the aims of the study is to be sort of a springboard to give people food for thought — the behavioral people and the ecologists — and get them excited to go out there and get a better sense of what's going on with these animals," Prendini said.

Follow Elizabeth Palermo @techEpalermo. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Elizabeth is a former Live Science associate editor and current director of audience development at the Chamber of Commerce. She graduated with a bachelor of arts degree from George Washington University. Elizabeth has traveled throughout the Americas, studying political systems and indigenous cultures and teaching English to students of all ages.