Is Technology Destroying Empathy? (Op-Ed)

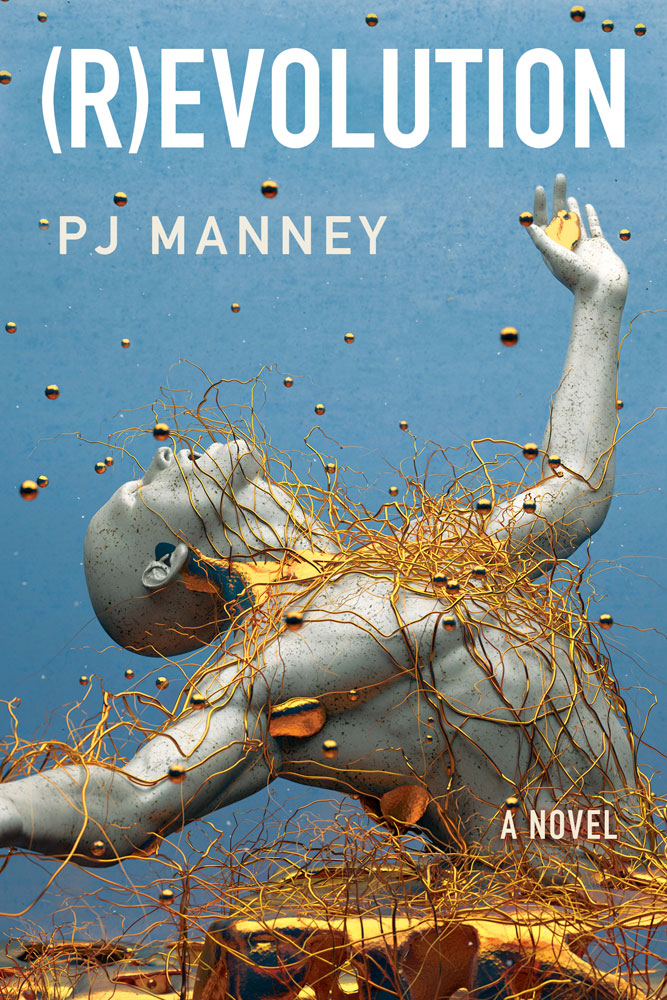

PJ Manney is the author of "(R)EVOLUTION" (47 North, 2015). She is a former chairperson of Humanity+, and a frequent guest host and guest on podcasts including The World Transformed. Manney has worked in motion-picture public relations at Walt Disney/Touchstone Pictures; story development and production for independent film production companies for such films as "Hook" and "Universal Soldier;" and writing for television for such shows as "Hercules - The Legendary Journeys," and "Xena: Warrior Princess." She also cofounded Uncharted Entertainment, writing and creating pilot scripts for television. She contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Empathy — the ability to share someone else's feelings — is perhaps the most important trait humans demonstrate. It's not a purely human attribute — in fact, even rodents possess it — but humans are particularly good at it. It allows us to love, learn, communicate, cooperate and live in a successful society. It doesn't matter what terms from evolutionary biology or psychology we use to define the behavior. What matters is that it makes the world go 'round and allows us to survive.

I wrote the science fiction novel "(R)EVOLUTION" (47North, June 2015) in part to examine what it would be like for a person whose brain has been technologically enhanced for empathy to the point that even the emotions and physical sensations his most deadly enemies would be felt. While that was fun (and dramatic!) to imagine, it's only a small part of the empathy story. ['(R)EVOLUTION' (US 2015): Book Excerpt ]

The heart of empathy

I have explored empathy creation since 2008, when I published a paper entitled "Empathy in the Time of Technology: How Storytelling is the Key to Empathy" in the Journal of Evolution and Technology. Empathy works on a neurological system that scientists are still trying to understand, involving a "theory of mind network" that includes emulation and learning. But at the center of empathy creation is communication.

We learn to be in the shoes of another person through real-life observation or storytelling. Communications technologies have evolved — from the beginning of language, to writing, to telecommunications, to information technologies, and soon to telepathic technologies with brain-computer interfaces. Regardless of the medium, repeated stories of the "other" have motivated the expansion of social inclusion and the liberalization of civilization for millennia.

In the 21st century, we use technology to communicate at a level unprecedented in human history. So, with so many opportunities to connect, why do we still not understand one another, and face such conflict?

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When others get in the way

Our brains' empathy systems have their share of problems. Most humans are generally good at empathizing with individuals. But we're not so good at trying to do the same for an entire nation or ethnic group. As Emile Bruneau, a neuroscientist at MIT, has demonstrated, people especially fail if the larger group embodies an ideology or cultural trait they disagree with. In fact, you might empathize well with your friends, but if you have particularly strong associations with your "in group," you will have decreased empathy for those you feel are not in your group.

But for all that information and exposure to new ideas, there are many examples of communication technologies that can destroy empathy. Let's begin with the ideological information silos of broadcast, print, website and social media, where conservatives or liberals only listen, read and watch their own thoughts repeated in recursive echo chambers of increasingly radical and exclusionary thought. [I Feel Your Pain, Unless You're From a Different Race ]

These media outlets not only destroy empathy, but actually move the needle of a group's acceptable actions to extremes. As soon as you demonize an "out group" — whether in racist, sexist or political rants — you have destroyed empathy. And the silos' internal success depends on it.

There is also too much information for us to take in. Our brains can't handle the barrage of emotionally draining stories told to us, and this leads to a negation or suppression of emotion that destroys empathy. The natural response is to shut down our compassion , because we are emotionally exhausted. Keith Payne and Dayrl Cameron, psychologists at University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, conducted research that demonstrates how choosing whether to experience or suppress a strong and empathetic emotion can alter our empathetic feelings. However, if we are conscious of the diminishment of empathy, we can recover it.

And finally, militaries use video game technology to suppress empathy and create a new type of soldier. In his exhaustive study "War Play" (Eamon Dolan/Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013), Corey Mead of City University of New York, demonstrates how the U.S. military has created a military-entertainment complex to recruit soldiers. However, gamers are recruited through video game sites to join air forces around the world. And as noted in the journal Military Medicine by Air Force psychologist Wayne Chappelle, et al., with this new military job description comes a new psychological issue that was not anticipated: Drone operators are suffering from their own forms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The stress of going between killing remote, faceless targets and incurring collateral damage, and then going home that afternoon to mundane activities such as coaching a child's football game is perhaps the most exhausting empathy swing of all.

Empathy, restored

But fortunately, there are as many (if not more) examples of communication technologies that can create empathy. From as far back as the first storytellers, humans have used the pain and suffering of "the other" to highlight the changes necessary to improve their own lives and communities.

Today, we can see that in the incredible emotional outpouring of support on social media around the tragic murders in Charleston, the quick change in opinion in the Western world regarding same-sex marriage and the growing support for equal rights for women and girls in their communities around the world.

Empathy is created when we discover the things we share. Verona, by Matthew Nolan, is a dating app that pairs Israelis with Palestinians. Using a cellphone, it asks questions like, "What are you most passionate about?" and finds the similarities in people who, based on religious and political issues, should otherwise have little in common. By emphasizing our common traits, empathy can lead to romance.

Virtual reality is a technology uniquely primed to be the ultimate form of immersive empathy. There is no frame or wall to contain or edit an image. You are simple there wherever your eyes look, experiencing what the protagonist could be experiencing. As Chris Milk of VR production company VRSE.works said in his TED talk, "How Virtual Reality Can Create the Ultimate Empathy Machine," "[Virtual reality is] not a video game peripheral. It connects humans to other humans in a profound way that I've never seen before in any other form of media. And it can change people's perception of each other. And that's how I think virtual reality has the potential to actually change the world." I hope he’s right about VR changing the world.

My favorite website that emphasizes both the differences and similarities among us is Humans of New York. The site, developed by Brandon Stanton, shares photographs of the inhabitants of the world's most cosmopolitan city and demonstrates how we can all relate to one another, regardless of who we are or where we're from. Even the United Nations saw the power of his work and sent him to the world's most conflicted regions to illuminate the lives of people there, minus the propaganda or political agendas of the existing information silos.

All technology is a tool. It is morally neutral and dependent on the intention with which it is used, for either constructive or destructive purposes. We have a choice: Do we want our communications to bring us together or split us apart?

To understand the power of communications technology, we must embrace the paradox: It will both destroy and create empathy. But we can actively choose creation. Remember that empathy is a muscle: The more you use it, the stronger it gets. So, flex those empathy muscles through storytelling and expand your notion of who is in your group. Or, be willing to fall prey to the increasing ideological polarization of our time and face the global consequences. It's up to us.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.