7 famous Fourth of Julys: How Independence Day has changed

Americans celebrated the first July Fourth in 1777, a year after declaring independence from England. The festivities have varied in the years since then, but several mainstays have emerged (parades and fireworks) while other patriotic pastimes (drunken toasts made by menfolk) have gone out of style. Here's a list of American traditions and famous Fourths.

1. July 4, 1777

Philadelphia held one of the largest Independence Day festivities for the country's first Fourth. The Continental Congress feasted at an official dinner, gave toasts and arranged a 13-gun salute. Americans also celebrated with speeches, parades and fireworks, said Adam Criblez, an assistant professor of history at Southeast Missouri State University, and author of the book "Parading Patriotism: Independence Day Celebrations in the Urban Midwest, 1826-1876" (Northern Illinois University Press, 2013).

"1777 in Philadelphia kind of sets the tone for July Fourth for the next 80 or 90 years," Criblez told Live Science.

Related: 10 Fabulous 4th of July Facts: Wild Celebrations

2. 13 toasts

Even the Revolutionary War troops celebrated the big day. On July 4, 1778, George Washington gave his troops a double ration of rum and ordered a cannon salute to mark the occasion, Criblez said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But the young nation was still figuring out how to commemorate its birthday, and most celebrations were held in New England, where the war sentiment was the strongest, he said. Still, celebratory practices spread. From the 1770s to the 1860s, most towns began the day with an artillery fire at dawn, if they had cannons on hand, Criblez said.

"If they didn't have cannons in the town, some of the men would get up and shoot their muskets into the air," he said. "That was kind of a 'Welcome to Independence Day' [announcement]."

Then, people would launch small but noisy fireworks, and parade from a public green or park to a courthouse or church, Criblez said. There, a lawyer, preacher or politician would talk for about an hour praising the country and its citizens.

At lunchtime, women would return home to make supper, and "the men would go off to the bar and spend hours drinking in the afternoon," Criblez said. A designated toastmaster would give 13 toasts, with the first always going to the United States, and the second to George Washington. Depending on the political affiliation, the toastmaster might toast different politicians or policies. Finally, the last toast went to the ladies, and impromptu toasts from other men would follow, Criblez said.

3. Birthday, death-day

Three presidents have died on the Fourth of July, and one died after having contaminated food or drink during Independence Day celebrations.

John Adams and Thomas Jefferson died within hours of each other on July 4, 1826, the country's 50th anniversary. Just five years later, James Monroe, the fifth president (1817-1825) and a founding father, died on July 4, 1831.

Related: 7 Great Dramas in Congressional History

Zachary Taylor, the nation's 12th president, died on July 9, 1850. That July Fourth had been blistering hot, and sources said the president had eaten a bunch of cherries and drunk iced milk and several glasses of water. He became ill and died days later. It's unclear how Taylor became sick, but the cherries, milk or water may have carried harmful bacteria, perhaps cholera, historians say.

4. Hello, baseball

"Whoever won had local bragging rights for another year," Criblez said.Baseball also gained popularity during and after the war. Regional leagues formed, and towns held Independence Day baseball tournaments.Fourth of July celebrations changed during the American Civil War (1861-1865). In light of the dead and wounded soldiers, many Northerners stopped the dawn artillery salute and turned away from large, public parades. Instead, these celebrants picnicked with their friends and family. These picnics were often fundraisers, where organizers might charge an entrance fee of a quarter and donate the money to the troops, Criblez said.

5. Patriotic sales

Before the Civil War, people who kept their businesses open on Independence Day were seen as unpatriotic. But that changed after the war. Stores and restaurants opened their doors and held sales in the name of patriotism.

It made sense if a store was selling red, white and blue decorations, but even clothing and furniture stores pushed the idea, calling shoppers patriotic for buying merchandise. Of course, the Fourth of July sale is still present, as are picnics, fireworks and, to some extent, playing sports such as baseball. "By the 1870s, you have what I would consider a pretty modern Fourth of July," Criblez said.

6. Morality message

In the early 1900s, the reform-minded Progressive movement aimed to improve American morality.

"One big target was the Fourth of July," Criblez said. "What reformers said is that people were getting too drunk and they were being dangerous by shooting off fireworks."

Organizers, such as local activists, doctors, police and firefighters, started the Safe and Sane Movement. In Cleveland, the movement prompted the city council to ban fireworks in 1908, and other cities followed suit in the following years, according to researchers at Case Western Reserve University.

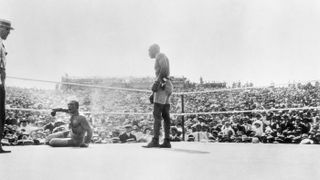

7. July Fourth fight

Boxing champion Jack Johnson, the first African American to hold the world heavyweight boxing title, made history when he kept his title on July 4, 1910.

Related: 10 Historically Significant Political Protests

"He was a pre-Mohammed Ali type of personality," Criblez said. "He wore fur coats. He liked to date white women, and he was outspoken. Basically, the boxing establishment didn't want him to be the champion anymore, and they began this search for someone who could take the belt from him."

The fight provided excellent entertainment for July Fourth celebrators. Jim Jeffries, dubbed "The Great White Hope," took up the challenge, but lost spectacularly to Johnson.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.