Child's Mysterious Paralysis Tied to New Virus

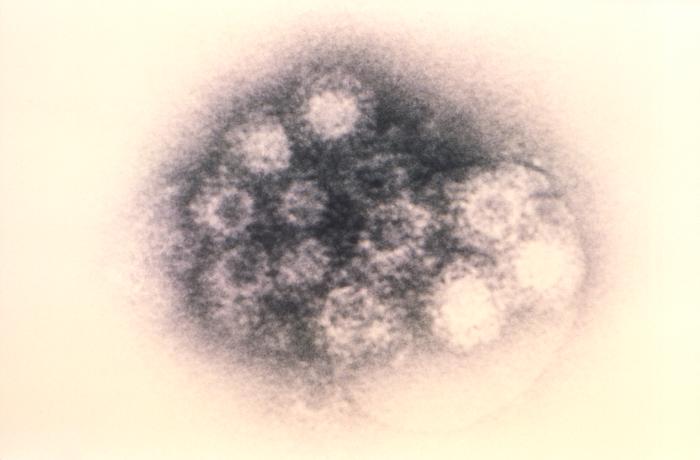

Mysterious cases of paralysis in U.S. children over the last year have researchers searching for the cause of the illness. Now, a new study suggests that a new strain of a poliolike virus may be responsible for some of the cases.

So far, more than 100 children in 34 states have suddenly developed muscle weakness or paralysis in their arms or legs, a condition known as acute flaccid myelitis, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Previously, researchers linked a virus called enterovirus D68 (EV-D68), which can cause respiratory illness similar to the common cold, with some of these cases.

But only about 20 percent of children with paralysis tested positive for EV-D68, and even in these cases, it wasn't clear if EV-D68 was the cause of the child's condition. [Top 10 Mysterious Diseases]

In the new study, researchers say that one case of paralysis, in a 6-year-old girl, is linked with another strain of enterovirus, called enterovirus C105. This virus belongs to the same species (enterovirus C) as the polio virus.

Although the new study doesn't definitely prove that enterovirus C105 was the cause of the girl's paralysis, it suggests that there are other viruses besides EV-D68 that are contributing to the outbreak of acute flaccid myelitis.

The study should make researchers aware that "there's another virus out there that has this association" with paralysis, said study co-author Dr. Ronald Turner, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Virginia School of Medicine. "We probably shouldn't be quite so fast to jump to enterovirus D68 as the [only] cause of these cases," Turner told Live Science.

The 6-year-old girl was previously healthy, but she caught a cold from members in her family, and developed a mild fever. Her fever and cold symptoms soon went away, but she was left with persistent arm pain. Then her parents noticed that the girl's shoulder appeared to droop, and she had difficulty using her right hand, the researchers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

At the hospital, the girl was diagnosed with acute flaccid myelitis, and a sample from her respiratory tract tested positive for enterovirus C105. This virus was only recently discovered, and the new study is the first report of enterovirus C105 in the United States, the researchers said. The girl tested negative for EV-D68.

Some tests can miss enterovirus C105, because of variation in the virus's genetic sequence, Turner said. This virus may have gone unrecognized in the current outbreak until now because it is relatively new, and can be hard to detect, he said.

"The presence of this virus strain in North America may contribute to the incidence of flaccid paralysis and may also pose a diagnostic challenge in clinical laboratories," the researchers said in their study, which will be published in the October issue of the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The researchers noted that enterovirus D68, and now enterovirus C105, have been found in the respiratory tract of children with acute flaccid myelitis, but so far, these viruses have not been found in the spinal fluid of these patients. That's important because a virus in the respiratory tract would not necessarily cause paralysis.

"You can have a virus in your respiratory tract that’s not doing anything to your nervous system," Turner said.

In order to more definitively link these cases of paralysis with enterovirus, researchers would need to find the virus in the spinal fluid, he said. But so far, tests have not found the virus there.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Measles has long-term health consequences for kids. Vaccines can prevent all of them.

100% fatal brain disease strikes 3 people in Oregon